![]()

1

Introducing John Hall, Master of Physicke

The earliest reference to John Hall is his admission to Queens’ College, Cambridge, aged 14, in 1589. The last is his will dated 25 November 1635. His Little Book of Cures, Described in Case Histories and Empirically Proven, Tried and Tested in Certain Places and on Noted People forms the most substantial account of his life and work among his patients in the locale made famous by Hall’s father-in-law, William Shakespeare. Most of the records relating to Hall concern his life in Stratford-upon-Avon, starting with his marriage to Susanna, the Shakespeares’ eldest child, in June 1607.

Hall was born in Carlton, Bedfordshire, the son of William Hall. John Taplin has written importantly and extensively on Hall’s family background in Shakespeare’s Country Families (Taplin 2018: 85–112). Taplin’s book is not widely known but is available for consultation in the Shakespeare Centre Library. Hall received his BA in 1593/4 and his MA in 1597. A doctorate in medicine was required for licensing by the College of Physicians of London or to teach at a university, but not otherwise. An academic doctorate was no more necessary as a medical qualification then than it is now. Although Hall never obtained, or claimed to have, the degree of Doctor of Medicine, his MA made him better qualified than most physicians in England at this time. Hall never used the title of Dr, nor was he addressed so by his contemporaries, though he has frequently and confusingly been granted it post mortem.

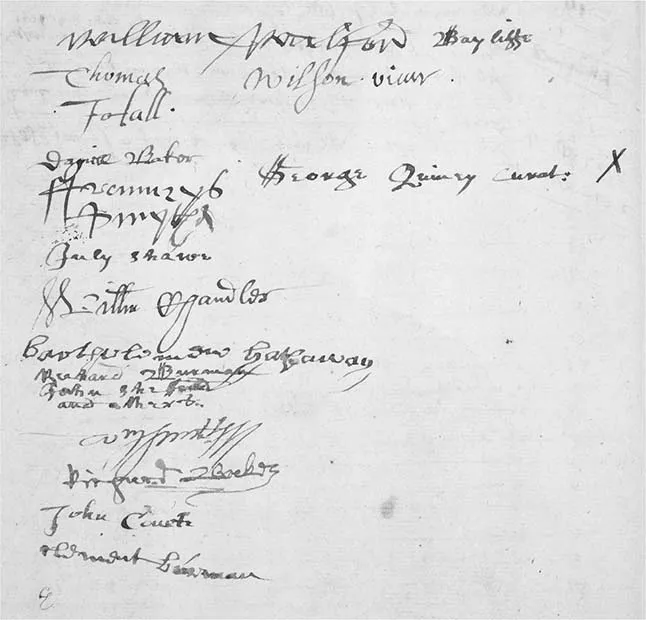

1 The signature of John Hall, churchwarden, Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon, 20 April 1621. Hall’s is the third signature down, just below Thomas Wilson (the vicar). Seventh down is July Shaw (who lived next door but one to New Place and who was one of the witnesses of Shakespeare’s will), and ninth down is Bartholomew Hathaway (Anne Shakespeare’s brother).

Of the 814 physicians practising outside London between 1603 and 1643, only 78 per cent had formally matriculated at a university (Raach 1962: 250). Of that 78 per cent, 40 per cent held BAs, 34 per cent MAs and 30 per cent were Doctors of Medicine. Hall may, like many English students, have travelled around the Continent and studied for a few weeks or months at one or more universities. If so, the purpose was to gain wider experience rather than a further degree. But short-term, unregistered students who paid their bills, and stayed out of trouble, commonly left no records behind them.

Outside London, physicians were supposed to be licensed by the local bishop but this was not, in practice, essential, and the records are patchy. A physician often applied for a licence only when a dispute arose with a patient or colleague, for the extra status it gave. There are no records of licences in the Worcester diocese before 1661, so either they have been lost, or none were granted. John was recognised as ‘professor of medicine’ (that is, practising medicine as a profession) by Stratford’s Church Court in 1622 (Brinkworth 1972: 148). This was a ‘Peculiar’ Court, sharing some responsibilities with the bishop but independent of him in two years out of three, so the recognition is equivalent to an episcopal licence.

Hall would have studied medical textbooks as part of his MA, but in addition ‘often a young physician would acquire practical bedside knowledge by working with an established physician’ (Wear 2000: 122). We know that Hall had access to medical books. As executor of his father’s will he received ‘all my books of physic’ (Marcham 1931: 25). This may indicate that Hall’s father was also a physician, but medical books were commonly owned by householders. In fact it tended to be their wives who provided the first line of medical care for the family and servants. Hall’s father, William, bequeathed books of astronomy, astrology and alchemy to his servant Matthew Morrys, but only on condition that Matthew should instruct John in these arts, if he wished to learn them. These kinds of books were far less common in a standard household library, and might be indicative of William Hall’s main interests. At some point, Morrys, too, moved to Stratford-upon-Avon and seems to have maintained friendly contact with the Halls; he named two of his children Susanna and John, after them. Two years after Shakespeare’s death, in 1618, John made Morrys a trustee, along with John Greene, of the gatehouse in Blackfriars that Susanna had inherited from her father (Schoenbaum 1987: 275).

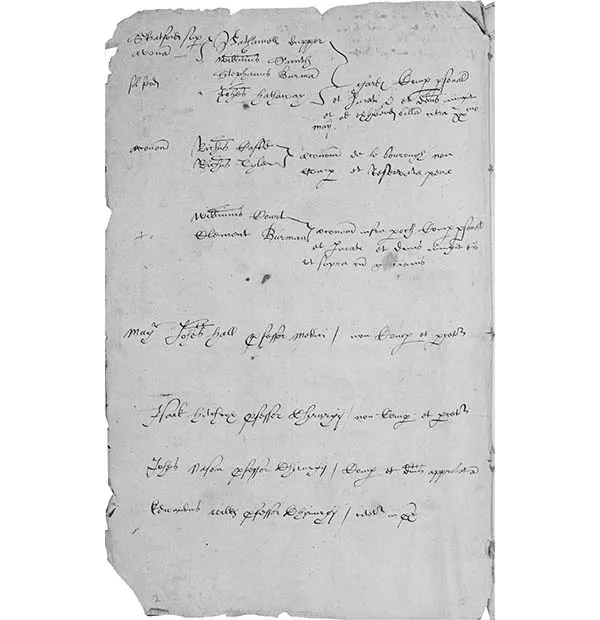

2 On 14 May 1622, John Hall was recorded as a ‘professor of medicine’ (i.e. a practitioner of medicine) in the records of the Stratford-upon-Avon Ecclesiastical Court (also known as the Bawdy Court). This is evidence of Hall being licensed in medicine by a court which had authority to license him when the bishop was not present. The record includes ‘He did not appear. Pardoned.’ Immediately below Hall’s name are three ‘professors of surgery’: Isaac Hitchcox, John Nason (similarly ‘pardoned’) and Edward Wilkes (‘Let him be cited for the next court.’). They would all have had to present their licences before the ecclesiastical authorities in order to continue their practice.

3 Title-page of The Treasurie of Poor Men (1560), a popular medical book of the day, written in English, and which emphasises by contrast Hall’s own motivation for writing. His text was in Latin and drew freely on other Latin medical texts. Hall wanted to demonstrate that he was a learned physician who was conversant with the best minds of his time.

It is likely that Hall also learned about medicine from his brother-in-law, William Sheppard, who had gained his MA at King’s College, Cambridge in 1590, and his doctorate in medicine in 1597. After marrying John’s sister, Sara, Sheppard moved to Leicester in 1599. It is likely that Sara had met William in Cambridge through her brother (since no other connection between the families is known), and that Sheppard invited John to accompany him to Leicester as his medical assistant. If so, then Hall would have had time for four or five years of supervised practice, and a visit to the Continent, before setting up on his own.

Settling in Stratford-upon-Avon

The reasons behind Hall’s move to Stratford-upon-Avon are unknown. Stratford was prosperous and had no resident physician, but the same applied to other small towns. The only identified link is through Abraham Sturley, estate agent to the Lucy family at nearby Hampton Lucy. The Lucys had estates near Carlton, so there might have been contact between Sturley and the Hall family there (Mitchell 1947: 10). There is no way of knowing whether John had met the Shakespeare family before his move.

John and Susanna Shakespeare married in Holy Trinity Church on 5 June 1607. Elizabeth, who was to be their only child, was christened on 21 February the following year. It is not known for certain where they lived before Susanna inherited New Place on the death of her father. Hall’s Croft was alluded to by the renowned Stratford-upon-Avon antiquarian Robert Bell Wheler in 1814. He says that he has seen ‘in some old paper relating the town, that Dr Hall resided in that part of Old Town which is in the parish of Old Stratford’ (Halliwell-Phillipps 1886: 321).

Dendrochronological evidence, commissioned by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, shows that the oldest part of Hall’s Croft, facing on to the road, was built from trees felled in the summer of 1613 (Anon. 1990). If they did live there for a while, it is likely that they rented it rather than owned it, since there is no record of sale, and the house is not mentioned in Hall’s will with his other two properties (a house in London and a house in Acton, Middlesex). Hall did own a ‘close on Evesham Way’, for which he paid a charge to the Stratford Corporation from 1612 to 1616 (Stratford-upon-Avon Corporation Chamberlain’s Accounts 1585–1619: 228, 245, 263, 276). It is likely that Hall used the close as a meadow for the horse he needed in order to visit his patients.

4 The house known as Hall’s Croft, the only surviving dwelling of the right period in Old Town that could have belonged to John Hall. The front of the building can be dated to around 1613. It is possible that the present house replaced an earlier dwelling on the same site, which might also have been the home of the Halls from the time of their marriage in 1607. This photo was taken in 1951 when the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust bought the house in order to preserve it for the nation.

John Hall and William Shakespeare

References to contacts between John Hall and his father-in-law are sparse. In 1611 their names appeared (with sixty-nine others) on what is thought to be a subscription list raising money to support a bill in Parliament for repairs to the highways (Bearman 1994: 44). The Halls would eventually inherit the 107 acres of land purchased by Shakespeare in 1602, land which would have been affected by the proposed enclosure at Welcombe in 1614. The clerk of the Stratford Corporation, Thomas Greene (a distant kinsman of Shakespeare), records a meeting in London on 17 November 1614, commonly assumed to have been with both Shakespeare and Hall, though Greene did not unequivocally state this. Greene visited ‘my cousin Shakespeare’, ‘to see him how he did’. In the conversation that followed, ‘He [Shakespeare] told me that they assured him they meant to enclose no further than to Gospel Bush […] and he and Mr Hall say they think there will be nothing done at all’ (Ingleby 1885: iii). Shakespeare was probably reporting Hall’s views based on prior discussions in Stratford, to emphasise their agreement on the issue.

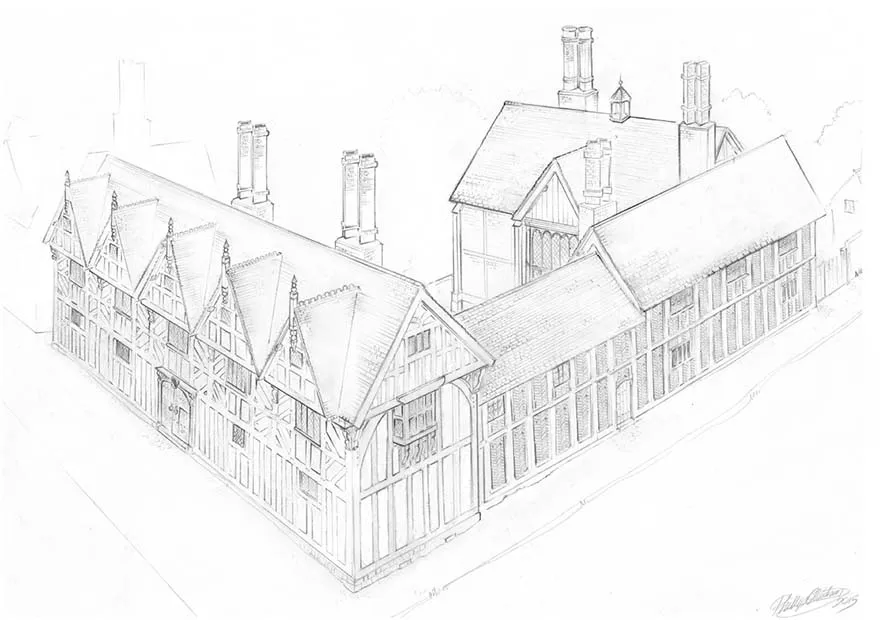

5 An artist’s reconstruction of New Place. Hall and his family moved in from 1616 on his wife having inherited on the death of her father, William Shakespeare.

In his will of 1616, Shakespeare made Hall joint residuary legatee and executor, along with Susanna (the main executor). Hall proved Shakespeare’s will on 22 June 1616 and seems to have discharged his duties satisfactorily (Schoenbaum 1987: 306).

Physicians in Shakespeare’s plays

The relationship between Hall and Shakespeare becomes important when considering whether Hall influenced Shakespeare’s portrayal of physicians in his plays, a debate that started in 1860 and has continued ever since (Bucknill 1860: 36). The occasionally disputed consensus is, first, that medical matters occur more frequently and are dealt with more seriously in the later plays, and, secondly, that Hall’s influence explains this. Two considerations rarely mentioned in this respect are that Shakespeare’s subjects and style changed over time, and that his characters are on stage for dramatic purposes, wider issues (such as the accuracy of medical references) being subordinated to the immediate pressures of plot and situation.

One does not need to invoke Hall’s influence to see that a physician like Dr Caius (The Merry Wives of Windsor, 1597–98) would be inappropriate in the later tragedies. Dr Pinch (The Comedy of Errors, 1594) is a schoolmaster, therefore a cleric not a physician. The scenes with a doctor in The Two Noble Kinsmen (1613–14) are by John Fletcher, not Shakespeare. Helen’s circumstances in All’s Well That Ends Well (1604–05) were uncommon but not unknown. Wives or daughters did sometimes inherit a practice and, with conditions, continue to practise physic (Pelling and Webster 1979: 183). In the medical marketplace of London or Norwich, about a quarter of unlicensed practitioners (excluding nurses and midwives), or one-eighth of all, were women. The dialogue between the Doctor and Cordelia in King Lear (1605–06) serves to slow down the action and build up tension before Lear’s wakening. The advice given to Cordelia as her father regains consciousness is general enough to be given by a Doctor in the 1608 quarto...