![]()

1

‘For her interest’: women in debt litigation

On 21 April 1627, Katherine Cuthbertson and Donald Cunningham, her husband, were ordered by the burgh court of Edinburgh to pay £20 6s 3d to Thomas Deans and Jean Borthwick, his wife, for cloth.1 While this case is largely unremarkable – in that it was just one of hundreds of debt cases entered into the burgh’s Register of Decreets for 1627 – it does highlight an important aspect of the networks of debt and credit that existed in Edinburgh in the early modern period. Specifically, it highlights the role that women played in these networks, for while Katherine’s and Jean’s husbands are both named with their wives in the case and presumably appeared with them in court, the reason for the debt is identified as being for the complete payment of four stone and one pound of lint bought by Katherine from Jean since the previous Martinmas. Nor is this case exceptional when considering the tens of thousands of debt cases entered into the court records of Edinburgh, Dundee, Haddington, and Linlithgow between 1560 and 1640. Rather, numerous examples exist in the debt litigation for all four towns that help bring to light the real and dynamic role that women played in the economy of debt and credit in early modern Scotland, whether acting as wife, widow, or servant.

This chapter examines the ways and extent to which women were involved in the debt and credit networks of Edinburgh, Dundee, Haddington, and Linlithgow between 1560 and 1640. Their involvement is explored through their appearances as both creditors and debtors in the burgh court records throughout the different stages of the life cycle. The categories of women under consideration were taken from the designations under which women were acting in debt cases, as given by the clerks of the courts. The main designations are those of wife, widow, or servant, although consideration of women who were not identified in one of these three ways will also be undertaken and their status explored. Whether a wife, widow, or servant, these records show women of all marital and social statuses suing and being sued, albeit to differing extents and for different reasons. Women accounted for more than 30 per cent of litigants in some of the debt litigation examined. The types of debts entered into these records included not only debts for money, but also debts for goods and services.

To date, relatively few works have discussed women’s roles in debt and credit networks in late medieval and early modern Scotland, and the majority of those that have do not approach the topic quantitatively. Testaments consulted from the seventeenth century for the Panmure estates in Forfarshire, and from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries for the Grandtully estates in Perthshire, indicate that the vast majority of those populations, including women, were involved in debt and credit relationships to some extent.2 Ewan suggests that women appeared in only 10 to 15 per cent of cases involving issues of debt and credit in the late medieval period in Scotland. However, Ewan makes the important point that cases in which the debtor and creditor were both satisfied in a timely manner tended to leave no trace, while transactions that involved small amounts of money did not make it to court either, often because they were too small to be worth pursuing, or because they had been contracted verbally, and therefore informally, and so were difficult to prove in a court of law.3 It is probable that many of the debts of those women responsible for small household purchases would have fallen into one of these categories, thus absenting them from the records.

Sanderson alludes to the role of wives in debt litigation in her discussion of wives’ contributions to their families’ incomes, noting that records rarely make clear whether a wife who appeared with her husband in a debt case was working with or separately from her husband. However, she presents only a smattering of examples to back up her assertions, rather than detailed quantitative analysis of the Commissary Court and Court of Session evidence to which she refers.4 Most recently, an examination of the Aberdeen baillie court (which was the type of court that succeeded the burgh courts examined for this study) for the late seventeenth century found that single and widowed women participated in at least one-fifth of the cases entered into that court, and that, more surprisingly, married women were routinely named in debt cases. In fact, 34 per cent of cases examined by DesBrisay and Sander Thomson featured at least one married woman.5 They attribute this high figure to the baillie court’s convention of naming wives both when they contracted debts on their own and when they acted with their husbands.

Outside of Scotland there have been a number of examinations of women’s roles in networks of debt and credit, as the complex relationships between debtors and creditors have long been a focus for historians of the medieval and early modern periods.6 Women were involved in these networks, albeit in relatively low numbers in some communities.7 McIntosh, however, has argued that virtually all women in England were deeply involved in debt and credit networks in the late medieval and early modern periods, and could manoeuvre skilfully within these networks despite a variety of legal and cultural handicaps imposed upon them.8 Chris Briggs has questioned this in his examination of credit and debt relationships in five rural communities in fourteenth-century England, in which he determined that women’s participation rate in debt transactions ranged between 10 and 18.1 per cent. He argues that the majority of women engaging in debt and credit networks would have been widows and single women because of the problems associated with attempting to recover a debt contracted by a married woman.9 Indeed, less than 4 per cent of cases in his study of two towns – Oakington and Horwood – featured married women as litigants, the vast majority of whom appeared with their husbands as joint litigants.10

Studies like those of McIntosh and Briggs acknowledge the impact made by Muldrew, whose own studies of the litigation records for a number of English towns encouraged and expanded the discussion of debt and credit networks in England.11 Muldrew argues that all people, both men and women, were drawn into what he calls a ‘culture of credit’ in early modern society through both desire and necessity. He found that people from nearly all levels of society took part in what was partially a self-regulating practice that crossed both gender and social status boundaries. Muldrew argues that the basis of this activity was not profit but the maintenance of an equitable balance between the social and economic factors that held the community together. Defaulting on a loan meant repercussions not just for the debtor and creditor immediately involved, but also for those linked by further degrees of debt and credit, and thus the well-being of the larger community.12

Muldrew’s studies are also important for their illumination of the extent to which women acted in debt and credit networks. His studies of a number of communities have shown that between 10 per cent and 36 per cent of litigants were women.13 However, one major caveat identified by Muldrew with regard to his sources is that the legal responsibility held by a husband for debts contracted by those in his household means that the role of wives has been underestimated in the debt and credit networks of which these households were a part, and that wives were, in actuality, much more active than the sources indicate.14 The percentages uncovered by Muldrew, however, suggest a strong correlation between the experience of Scottish and English women in debt litigation in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as they are comparable both with those found by DesBrisay and Sander Thomson in Aberdeen and those this study has found in Edinburgh, Dundee, Haddington, and Linlithgow.

Women in debt litigation in early modern Scottish towns

Women certainly had a great deal of power over their own affairs in the burgh court records for early modern Scotland that were consulted for this study. A close reading of this debt litigation can bring to light information concerning the role of women in debt and credit networks during this period.

The recording of the debt litigation in these records is usually both straightforward and fairly formulaic, particularly with regard to the records for Edinburgh, Haddington, and Linlithgow. The debtor is ordered by the baillies of the court to pay the creditor a certain amount of money. The majority of cases deal with successful actions, but some cases in which a defendant was absolved of a debt were also recorded. The reason for the debt – typically for food, drink, house rent, cloth, borrowed money, or a combination of two or more of these items – then concludes the decreet. Men are typically identified by their profession or trade in these decreets. Women, however, are usually identified in one of three ways: either by their marital status, as a wife or widow, by a relational status, as a mother, daughter, or sister to another (normally a man), or as a servant. Servants, who were found most often in the Edinburgh records, could be identified either relationally, as the servant of a merchant, widow, or other member of the community, or simply by the term ‘servant’.15 Records from Dundee, meanwhile, tend to identify men by their occupations less often than do the records of the other towns. Similarly, the Dundee records are less likely to identify a woman by her marital status. While woman who appear with their husbands are identified as wives, women who appear alone in the court are usually not identified with any relational descriptor at all.

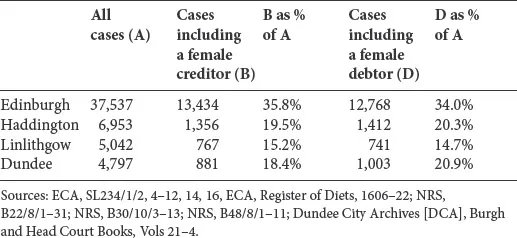

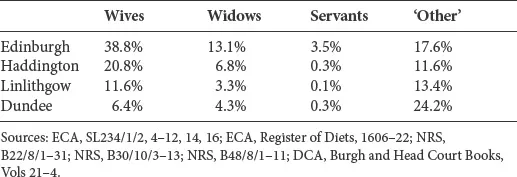

As illustrated by Table 1.1, women maintained a strong presence as both creditors and debtors between the late sixteenth and mid-seventeenth centuries. Women in Edinburgh in this period were clearly more active – or recorded as being more active – as debtors and creditors than were women in Dundee, Haddington, or Linlithgow. There are several possible reasons for this, the first being that Edinburgh women simply contracted debts more often. Edinburgh’s position as Scotland’s premier town might have offered greater opportunities to purchase, sell, or rent goods and services, which in turn might have necessitated more stringent recording of these transactions in order to ensure payment. Edinburgh’s larger size and population, as well as its appeal to immigrants and frequent turnover of population, might have also necessitated a more stringent process for the recording of small debts, rather than a simple agreement between friends or neighbours, to ensure that those debts were repaid. While the percentages in Table 1.1 clearly show that women were participating in the economies of debt and credit, more information can be gleaned by breaking down these percentages into different classifications of women, as shown in Table 1.2. This allows the differing legal statuses of wives and widows to be taken into consideration. Widows were legally allowed to enter into contracts, while wives required the permission of their husbands. Thus, it would be expected that widows would be visible in debt and credit transactions, while the presence of wives would be covered by the legal responsibility of their husbands. As will be shown, this was not the case. It was also deemed necessary for this study to include a fourth category of women, designated as ‘other’. This grouping acted as a catch-all category for those women featured in the records who were identified by a designation other than the first three designations of wife, widow, or servant, or by no designation at all. It is possible, and even probable, that some women entered into this ‘other’ category were a wife, a widow, or a servant, but because these statuses cannot be proven, the decision was taken to keep them separate.

The first three of these designations – wife, widow, and servant – are largely self-explanatory. A wife was the spouse of a husband. A widow was a woman who was the ‘relict’ of a deceased husband, or identified under her own name along with the descriptor ‘widow’. A servant was a woman identified as the servant of a man, a husband and wife, or a widow. The fourth category of women, who were identified using some other designation, or by no designation at all, is more problematic, particularly with regard to the Dundee evidence. The clerks of Dundee recorded women’s marital statuses ...