This is a test

- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

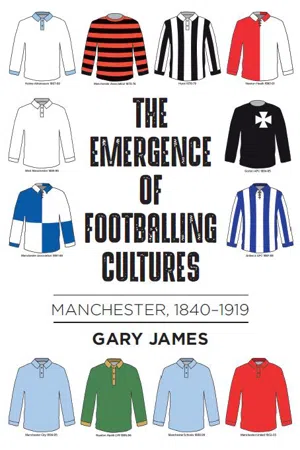

This study of Manchester football during the period 1840 to 1919, by leading sports historian Gary James, contextualises the sport's emergence, development and establishment through to its position as the city's leading team sport, and identifies the communities who developed football.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The emergence of footballing cultures by Gary James in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Folk football and early activity

Manchester

To understand the role that football plays in Mancunian life it is first important to appreciate how the city and its surrounding area evolved, and how sport took a hold of the region. Today Manchester is known throughout the world primarily for its football. This recognition of Manchester’s footballing culture has developed in the wake of the conurbation’s footballing successes since the beginning of the television era in the 1950s, but the city’s roots go back much further. As the eagle on Manchester City’s former badge (1997–2016) and on United’s 1958 FA Cup final shirt signifies, the city of Manchester began as a Roman outpost.1 Mamucium, a Latinised version of a Celtic word meaning ‘breast-shaped hill’, was established in the year 79 CE, close to the junction of the rivers Medlock and Irwell. Over the course of the following three hundred years a small town became established around the original Roman fort. The Roman presence lasted until the year 410, following which the Saxons renamed the area Manigceastre before, in 870, the Danes seized control. During the tenth century the church of St Mary was established a mile north of the old fort, where a town had started to develop in what became the present-day cathedral area of the city. In 923 a Mercian force sent by Edward the Elder is understood to have expelled the Danes and then went on to repair and garrison Manchester’s old Roman fort. The whole district between the Mersey and the Ribble was wrested from Danish Northumbria and the diocese of York and was reorganised as a royal frontier domain within the Mercian diocese of Lichfield. Salford became a great royal manor and the centre of the civil administration of the south-eastern part of the district, but Manchester remained the ecclesiastical centre.2

After the 1066 Norman invasion the manor of Manchester, or Mamecestre as it was recorded in the Domesday book, was valued at £1,000 and was given to Roger de Poitou, who had helped William the Conqueror to victory. Roger kept the manor of Salford for himself but divided the rest of his newly acquired lands among other Norman knights. In 1129 he passed the barony of Manchester to Albert de Gresley and it remained in his family for several generations.3 In 1223 Manchester gained the right to hold an annual fair, which was staged at the site of the present-day St Ann’s Square, and in 1301 the town became a free borough. A survey of the land by Thomas de Gresley, the lord of the manor, noted several important areas, including what became central Manchester and neighbouring hamlets, such as Ardwick: ‘There is a mill at Manchester, running by the water of the Irk, value ten pounds, at which the burgesses and all the tenants of Manchester, with the hamlets, and Ardwick, Pensham, Crummeshall, Moston, Notchurst, Getheswych, and Ancotes ought to grind.’4 At this time Gresley granted a charter establishing a system of local government for Manchester and this was to last for the following five centuries.5 Later in the fourteenth century Manchester’s link to the clothing trade became established following the arrival of a community of Flemish weavers, and the industry developed, making Manchester a leading centre for the textile industry. During the sixteenth century local prosperity ensured that the people suffered fewer hardships than were experienced in many other English towns, and the demand for Manchester cottons continued to grow, but the trade did not dominate until after the middle of the seventeenth century.6 By the 1500s Manchester had developed, with the collegiate church of St Mary, the present-day cathedral, being established, and within a century a Free Grammar School was founded. This was followed in 1653 by Humphrey Chetham’s hospital and library, often considered the first free public library in Europe, close by. However the town’s growth was not accompanied by any adequate provision for sanitation and on several occasions the town suffered with the plague, notably in 1605, when about 1,000 people died from it.

By this time the Mosley family owned the rights of the lord of the manor. Under their control during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries there was major change, with the erection of a second church, St Ann’s, in 1709. Between 1719 and 1739 no fewer than 2,000 new houses were built. In July 1761 the opening of the Bridgewater canal, which reached Castlefield, close to the site of the old Roman fort, allowed coal to be easily transported into the heart of Manchester, while cotton was transferred via the Mersey and Irwell rivers, which had been made navigable from the 1720s onwards. The Bridgewater canal opened in stages, with the section between Worsley and Manchester established in 1763. Over the following decades it was extended to Runcorn and linked to other canals such as the Trent and Mersey and the Leeds and Liverpool. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries saw Manchester continue to grow at a phenomenal rate, and prominent civic buildings were opened, including the first infirmary (1752), a subscription library (1756), the Theatre Royal (1775), the Concert Hall (1777) and the Assembly Rooms (1792), with the Portico Library following in 1805.7 During the 1770s Manchester was said to have ‘extended on every side, and such was the influx of inhabitants that though a great number of houses were built, they were occupied even before they were finished’.8 The city had strong trading links across Europe, prompting historian John Aikin to comment in 1795 that ‘the town has now in every respect assumed the style and manners of one of the commercial capitals of Europe’.9 Manchester was one of the fastest-growing towns in late Hanoverian England and between 1775 and 1830 the population ‘increased at least three fold’ and its wealth was growing as a result of its development.10

By the first decade of the nineteenth century the population had reached approximately 80,000 and Manchester was considered ‘the icon of a new age: industrial, urban, and ferociously modern’.11 It was never solely a mill town in the way some of its neighbours were, and in 1815, when employment in the cotton industry was at its height, the estimated number of cotton workers was less than 12 per cent of the population.12 Nevertheless, cotton was important to the city and by 1816 there were eighty-six steam-powered spinning factories in Manchester and Salford, with the number increasing over the following decades, so that by 1841 there were almost 20,000 people employed in cotton manufacture.13 The importance of the cotton industry to Manchester’s economy was illustrated in a survey of the workforce carried out in 1839 which revealed a range of supporting businesses, such as warehouses, offices and packaging companies, and their presence helped to shape Manchester’s physical appearance.14 Between 1820 and 1830 the number of warehouses in the city had grown from 126 to over 1,000 as the city moved away from production and into distribution. This growth continued, and between 1841 and 1861 the number of warehouse workers increased from 5,000 to 12,000; the number of clerks rose by 2,000 to over 5,000; and the numbers engaged in the transport industry, including porters, carters, and railway workers, quadrupled to almost 8,000.15

Both the cotton industry and the subsequent period of industrialisation saw a significant influx, swelling the population from 142,026 in 1831 to over 400,000 by 1871. This growth in population ‘breached existing administrative boundaries’, meaning that analysis of census figures can be misleading and the age-old question of what is Manchester rears its head once more.16 Manchester was allowed its first Members of Parliament under the Great Reform Act of 1832 and it became a borough in 1838, obtaining city status in 1853. The Industrial Revolution and subsequent growth of both industry and population had prompted an expansion of the suburbs around Manchester, with the south of the city seeing middle-class developments and east Manchester becoming characterised by working-class districts.17 The disadvantage for Manchester in being the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution was the decline in the quality of life of the city’s poor. The Reverend Richard Parkinson, canon of Manchester, had recognised this as early as 1841 when he commented that ‘there is no town in the world where the distance between the rich and the poor is so great or the barrier between them so difficult to cross’.18 By 1861 approximately 20,000 were employed in engineering and this number continued to increase, making metals and engineering the leading industries in Manchester, employing twice as many as cotton, by the beginning of the twentieth century. Textile work continued in the form of clothing manufacture in workshops spread across the city and the wider area.19

Demonstrating how much land now formed part of Manchester’s conurbation, it should be noted that while the population increased four-fold in the first half of the nineteenth century, the urban area grew seven-fold.20 Manchester’s expansion in the early nineteenth century was viewed positively by some, Joseph Aston commenting: ‘during the last fifty years, perhaps no town in the United Kingdom, has made such rapid improvements as Manchester. Every year has witnessed an increase of buildings. Churches, Chapels, places of amusement and streets, have started into existence.’21 This growth came partly because Manchester was almost entirely devoid of a resident aristocracy by 1825, allowing a ‘relatively unencumbered urban development’ without the constraints of a landowning class, differentiating Manchester from other cities such as Birmingham.22 Their place was filled with ‘hard-headed shopkeepers’ and businessmen who, via the local council, had taken the power, prestige and patronage relinquished by the aristocracy by the middle of the nineteenth century.23 This power was based on consensus and negotiation rather than on inheritance and social standing and the commercial class appeared to be more focused on social progress than the aristocracy were. However, this rapid urban development was highly beneficial for some Mancunians who were ‘rewarded for speculative ventures, but catastrophic for others, as bad luck, poor judgement and external economic factors produced financial ruin’.24

In 1819 one of the most important moments in Manchester’s history occurred when the reform meeting held in St Peter’s fields, close to present-day St Peter’s Square, ended with the infamous Peterloo Massacre. The meeting was planned to be a visible but peaceful demonstration against the Corn Laws and was also campaigning for parliamentary reform, but it became much more than that, with an estimated eighteen deaths and almost 700 people suffering serious injury. The authorities tried to put an end to the meeting shortly after it started and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of figures and tables

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Manchester map

- Introduction

- 1 Folk football and early activity

- 2 Origins

- 3 The earliest club

- 4 Footballing communities

- 5 Formation of clubs

- 6 Organisation and competition

- 7 Football as a business

- 8 Identity

- 9 Scandal and rights

- 10 A strained relationship

- 11 School, work and leisure

- Conclusion

- Index