eBook - ePub

Missionary families

Race, gender and generation on the spiritual frontier

This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Presents an innovative argument for the significance of missionaries' familial relations in the philosophy, conduct and outcomes of mission work during the nineteenth century.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Missionary families by Emily Manktelow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

‘Originally,’ wrote Richard Lovett in his centenary history of the London Missionary Society (LMS) in 1899, ‘the idea was that the Christian family would be an educative and helpful influence to the natives, and as the European children grew up they also would take part in missionary labour, and be all the better qualified for the work from their intimate knowledge of native life.’ So far, so good. Unfortunately ‘this was a fond imagination, but, like so many others, it fared badly under the rough trial of experience’.1 Throughout its history the LMS was constantly disappointed with the behaviour and function of missionary families. Forced at every institutional level to deal with them (much against its will), the LMS seemed to find nothing but difficulty in these families, even as individual missionaries wove the family into mission theory and objectives. Wives put domesticity before their work; children turned to the worst kinds of juvenile deviancy; and fathers complained bitterly and constantly about their parental autonomy. This was not what the LMS had envisioned when it counselled that at each station they would have ‘a little model of a Christian community, an economy of well regulated families’.2

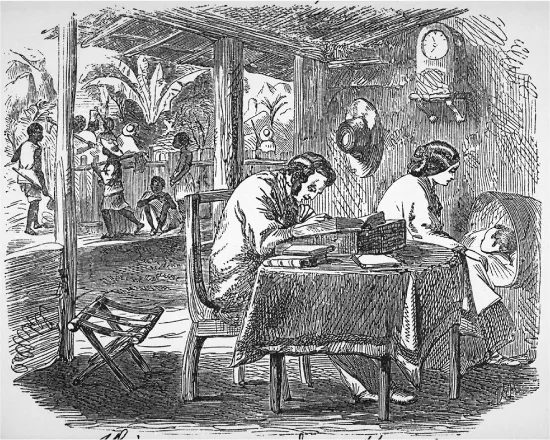

Figure 13 ‘The missionary at home’.

Missionary families were the building blocks of an enterprise that spanned the globe in the nineteenth (and twentieth) century. Around 10,000 missionaries were dispatched from Britain in those first hundred years; over 1,300 by the LMS alone – all this, ‘not including the wives’, yes, but also not including the children, the grandchildren, the sisters and aunts. For thousands of people around the world, missionaries were the point of contact between the local and the global. These exchanges were managed by missionaries, but were mediated by families – and while Lovett’s quote eloquently demonstrates both the LMS’s ambivalence about the role of the family, and the mission historian’s tendency to ignore their influence, the mission family should not be ignored in the history of this cultural, material and spiritual encounter.

This book explores both the institutional and the intimate history of the missionary family. This is not a project many historians of Christian mission have pursued, and although there are some notable exceptions, mission historians tend to operate within a system of assumed knowledge: that is, we all think we know about the missionary family (after all, it is a constant background presence in the writings and ruminations of the missionaries themselves), but without a real working knowledge of how it fitted into the missionary enterprise, the lived experience of individual missionaries, and the mission’s global and spiritual objectives. In fact, the LMS at least found itself constantly embroiled in the intimate history of the family, much against its will, and individual missionaries struggled to balance the personal and the professional in such a way that ultimately the personal became the professional; the private became the public, most famously through the precepts of the civilising mission, but more generally in the everyday experience of mission lives. This book provides the context for this re-imagination of the mission experience.

At the end of eighteenth century the Pacific voyages of Captain Cook, the so-called ‘swing to the east’ occasioned by British victory in the Seven Years War, and the consumer revolution in imperial goods all came together to spark a wide-ranging British interest in the non-Christian world.3 That, combined with a dramatic reassessment of Britain’s religious trajectory through the evangelical revival (which stressed vital and personal religion over nominal and ceremonial religious performance), culminated in the 1790s with the foundation of numerous evangelical missionary societies whose existence shaped, and were shaped by, the parameters of Britain’s global encounter.4 Cook’s voyages in particular were ‘as the spark to tinder’ in the minds of early missionaries and mission supporters,5 and in the imperial world there was developing a ‘many-sided reassessment of Britain’s overseas responsibilities’, spurred on by abolitionist rumblings for the ending of the slave trade,6 and evangelicalism’s active engagement with community, nation and world.

The LMS, with whom this book is primarily concern, was founded within this context in 1795 by a group of evangelically minded individuals inspired by the Apostolic injunction to ‘Go ye into all the world, and preach the Gospel to every creature.’7 It had been preceded some three years earlier by the Baptist Missionary Society (founded in 1792) and was followed by the Edinburgh (Scottish) and Glasgow Missionary Societies in 1796 and the Church Missionary Society in 1799. These organisations would ultimately dispatch thousands of missionaries across the globe, initially unschooled, pious and apostolic; increasingly educated, professional and socially oriented. Mission activity crept into the four corners of the globe, impacting profoundly on indigenous peoples, the domestic social and cultural history of Britain itself, and on the broader history of Britain’s global century.

Despite this, the figure of the missionary him/herself, the nature of missionary stations, and the configurations of the missionary family remain obscure in much mission writing. Thomas Beidelman evocatively remarked, in the 1970s, that while anthropology has been increasingly interested in the study of modern societies, such work ‘dims with the colour line’, concerned with ‘exotic societies, but not with … the study of colonial groups such as administrators, missionaries, or traders’.8 Excepting important work undertaken on female missionaries,9 this remains a problem.10 Why mission scholars are reticent about writing anthropologically or historically about missionaries themselves Beidelman unintentionally acknowledged when remarking that while there have been ‘some highly sophisticated studies of mission by missionaries themselves … none of these writers appears to have had any interest in relating his findings to theories or problems outside the mission community’.11 In the words of Lovett,

missionary history is hardly worth the telling, unless it leads the reader to bring the experience of the past to bear upon the missionary problems of to-day, and enables him to solve the problems of to-day by the insight and the instinct, as it were, that reward the patient investigator into the deeds and the purposes of those who have gone before. A knowledge of the history of all the societies is of little service unless the conscience of the reader is enlightened, his love for those for whom Christ died deepened, and his zeal for the furtherance of the great missionary cause strengthened.12

From its inception, then, mission history, hagiography and missiology have been intimately linked: an uncomfortable beginning for historians now more interested in the social, cultural and economic dynamics of what was never a purely spiritual encounter. Breaking away from earlier traditions of hagiography and missiology has been the more recent objective of mission historians, and one strikingly achieved. Mission history has grown into a complex and sophisticated discipline, from the books of A. F. Ajayi and Emmanuel Ayandele in the 1960s, to the more recent works of Brian Stanley and Andrew Porter, the Comaroffs and Catherine Hall (among many others).13

The price of this historical legitimacy, however, has been a focus on the public history of the missionary endeavour, brought about by a close (and fruitful) association between mission history and the history of imperialism.14 This has meant that while imperial history itself has embraced the importance of studying the personal and the intimate (particularly in the field of sexual relationships and their role in constituting racial categories and the colonial encounter),15 mission history has been most effectively mined in its public intersection with imperial history, and has lagged behind in explorations of the affective and the personal. Taking the missionaries themselves as a legitimate site for historical analysis divorced from their effect on public processes of ‘modernisation’, ‘civilisation’ and colonial engagement, remains scholastically taboo.16

The trouble is, this way of approaching mission history (in the words of mission historian Natasha Erlank),

perpetuate[s] the dominance of [a] kind of history which give[s] precedence to attitudes and relationships that have to do with public ‘political’ issues, mediated in public spaces. This kind of history privileges political and public events and in doing so dismisses the importance of events and relationships that occur in more private arenas, including the home.17

‘The public sphere is assumed to be capable of being understood on its own’, notes political scientist Carole Pateman, ‘as if it existed sui generis, independently of private sexual relations and domestic life.’18 The ever-present proximity of mission history’s problematic predecessors has in some ways obstructed a fruitful avenue for analysis: missionaries themselves as personal, emotional and three-dimensional individuals in the historical landscape. It was with this in mind that this project was embarked upon; not with an idea of the necessarily public importance of private life, but with an understanding of history as rooted in the intimate and the personal, historical sites that have value in themselves, and not necessarily as ciphers for deeper understandings of public history. After all, ‘historians of colonialism cannot write “against the grain” of imperial history and state-endorsed archives without attending to the competing logics of those who ruled and the fissures and frictions within their ranks’.19

As such, this project has been much inspired by the words of anthropologist Greg Dening, who has argued that ‘to write the history of men and women one has to compose them in place and in their present-participled experience’.20 With regard to missionaries, thinking about their role in a family, evolving through the life-cycle, is to ‘present-participle’ them: to acknowledge their humanity, their emotions, their reality as living beings. To analyse their impact, historians must analyse (emotionally and critically; spiritually and historically) their existence, and the day-to-day fabric of their lives. Mission history, the missionary, and the missionary family are legitimate sites of historical enquiry on their own terms. Catherine Hall has certainly recognised this in her powerfully complex reading of the interrelated histories of Britain and Jamaica:

Public metropolitan time was cross-cut with public colonial time; both were cross-cut again by familial time, private time, the time of birth, emigration, marriages, new homes and death. It was these cross-cutting patterns which constituted ‘imperial men’, and out of which they made, and told, their stories.21

Mission and colonial historian Sujit Sivasundaram, meanwhile, has recently urged that ‘more attention should be paid to the lived experience of evangelicalism’.22 In the period covered in this book in particular (the nineteenth century), family life and the lived experience of family structures were integral parts of the lived experience of evangelicalism, increasingly instrumental in an emerging middle-class evangelical domesticity.23 ‘Now the wheel has come full circle’, notes mission historian Neil Gunson, ‘as missiologists and academic historians look again at mission origins and mission values.’24

For me the present-participling of missionary history means creating and exploring a familial context in which to place missionaries, their thoughts and actions. I approached this project in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures

- General Editor’s introduction

- Acknowledgements

- List of abbreviations

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The rise and fall of the missionary wife

- 3 Missionary marriage

- 4 The missionary family

- 5 Missionary mothers and fathers

- 6 Missionary children

- 7 Epilogue: second-generation missionaries

- 8 Conclusion

- Appendix

- Bibliography

- Index