![]()

1

The interwar house: ideal homes and domestic design

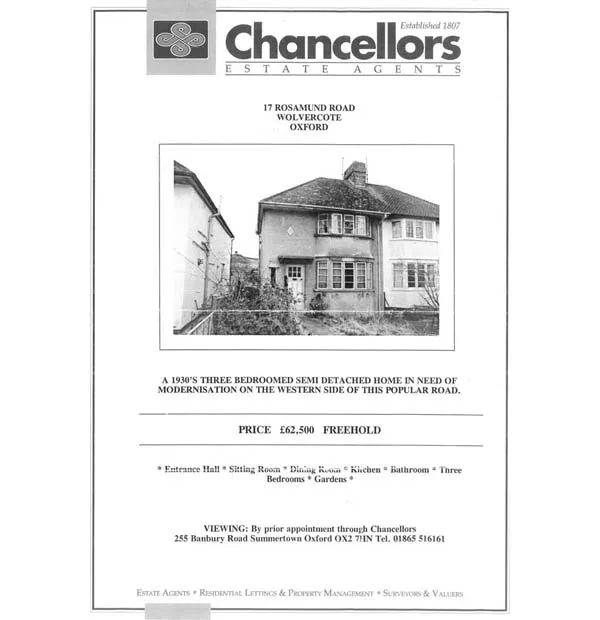

Number 17 Rosamund Road, Wolvercote, Oxford

A 1930’s three bedroom semi detached home in need of modernisation on the western side of this popular road.

* Entrance Hall * Sitting Room * Dining Room * Kitchen * Bathroom * Three Bedrooms * Gardens *1

We arrived at number 17 Rosamund Road, Lower Wolvercote, a village on the edge of Oxford’s Port Meadow, on our bicycles on a sunny day in May 1995 (Figure 1.1). We were surprised to be there as we had previously ruled the area out as too expensive. We were newly married and house-sitting in Oxford, having moved there from London where we knew we had no chance of buying a house. My husband James had a junior lecturer post at the University of Oxford, and I was a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Royal Holloway University of London. We may have had middle-class professional jobs but we were on modest salaries and still recovering from the financial effects of years of full-time postgraduate study. The house was just within our budget and ticked the box of ‘needing modernisation’.

James clutched the estate agent’s details. ‘What do you think?’, he said to me. The house had a pitched roof with a central chimney stack. The façade was rendered and the only decoration was a moulded diamond above the front door. The front door itself was the original wooden one with six panes of glass occupying its top third. There was a large double bay with the original metal Crittall windows with their distinctive small rectangular panes, which appeared slightly at odds with the tall narrow window to the left of the front door, which had a more ‘modernistic’ look. The windows and door had not been replaced with uPVC I noted with relief. ‘Well, the unpainted render makes it look a bit gloomy and I would have preferred it to look a bit more “modernistic” like the houses in Botley, but I like the diamond above the front door and it’s got its original Crittall windows. I guess it’s sort of cottagey Arts and Crafts. I like the double bay’, I said. The garden gate was rusting and lopsided and the surprisingly big front garden (a depth of twenty-six feet (7.9 m), according to the estate agent’s details) consisted of a tangle of bindweed and brambles. We made our way up the path, James opened the front door and I gasped.

1.1 Leaflet by Chancellors Estate Agents advertising 17 Rosamund Rd, Wolvercote, Oxfordshire, 1995

Entrance Hall: with stairs off, two understairs [sic] cupboards, gas fire. I felt like a time traveller. The first thing we saw, directly opposite the front door, was the staircase, fitted with a faded and heavily worn stair runner patterned with geometrics and florals, held in place by dirty, copper-coloured stair clips. To the right, the floor of the narrow hallway was covered in grubby linoleum in more geometrics and florals in a palette of turquoise, orange and brown. The hall was lit by a mottled orange and white alabaster bowl suspended from the ceiling on three chains, filled with the customary dead flies. Immediately to the right in the hall was a door, original I noted (rectangular panel at the top, with a horizontal band underneath and then vertical panels), that opened into the front room.

Sitting Room: 12′ × 11′ [3.6 × 3.3 m] into alcoves and bay window to front, picture rail, central tiled fireplace. The front room was pale green below the picture rail, with yellowing white paintwork above (Plate 1). The ceiling was thick with cobwebs. Each wall was edged with narrow cream and brown textured border paper to give a half-frame effect. On the party wall sat a stepped ‘Devon’ tiled fireplace in mottled beige tiles with powder blue tiles in the top corners forming a diamond shape.2 A compact, brown, leatherette three-piece suite in a style that combined ‘modernistic’ curves with ‘Jacobethan’ studs took up most of the available floor space, even though its proportions were very small.3 It consisted of a two-seater sofa and ‘his’ (with a winged back) and ‘hers’ armchairs. The little area of floor we could see was covered with unfitted linoleum and the foot or so of floorboards that showed around the edges were stained dark brown. Another alabaster bowl hung in the centre of the room. The room was tiny but it was lovely and bright because of its bay window.

Heading back into the hall, there was a door to the left under the stairs. I opened it and found a rudimentary larder with a small, high, square window, through which the sun streamed, with a stone slab underneath. Straight ahead at the end of the hall was another door, which I assumed led into the kitchen. Opening it we found the bathroom.

Bathroom: With bath and wc [sic]. Immediately to the left was a toilet with a high cistern. Straight ahead was a stained and alarmingly short rolltop bath with peculiar ‘globe’ taps with spouts directly under the handles rather than in the customary ‘h’-shaped bend. There was more lino on the floor. Only later did we realise that there was no washbasin in the bathroom.

Dining Room: 12′ × 9′6 [3.6 × 2.8 m] into alcoves, central tiled fireplace, picture rail, television aerial point. At the bottom of the hall to the right was another door, leading into the dining room. Crammed into this room on the right was a sideboard that combined bulbous ‘Jacobethan’ legs and carved ‘modernistic’ details; opposite it was a small, green, leatherette two-seater sofa. On the left-hand wall there was a folding gate-leg table and chairs. The right-hand wall featured another tiled fireplace in beige, plainer than the one in the front room. Behind the sofa on the far wall a window overlooked the long rear garden. To the left of it was another door. To get to it, we had to walk around the table and squeeze through the gap between it and the sofa.

Kitchen: 8′8 × 8′ [2.6 × 2.4 m]. With sink unit, gas point, side door outside. We entered through the door into a tiny square kitchen (Plate 2). The walls were covered in dirty, cream, peeling eggshell paint and thick with grease. Underneath the window on the centre of the far wall that looked out on to the garden was a large, deep, porcelain ‘Belfast’ sink. Either side of it was a narrow, enamelled, metal-topped table. There were some rudimentary shelves mounted on the dividing wall. On the right-hand wall was an old gas cooker. Perhaps the left-hand wall had once had a dresser or a kitchen cabinet against it?

A rotting back door on the left opened out to the side path and there was a ‘side store’ built into the external wall of the house, originally intended for storing coal. At the end of the path a gate opened into a long, narrow garden ‘with a depth of approximately 70 [feet] [21 m]’, which, the estate agent’s details noted, ‘is currently overgrown’.4 It was choked with weeds and vicious brambles that pushed at the back wall of the house. On the left was what looked like the original waist-height wire fence dividing the garden from the house next door, and on the right a decrepit wooden fence that separated the garden from the one belonging to the adjoining semi. We retraced our steps through the garden and the ground floor of the house and headed upstairs.

Landing: With access to roof space. Off the landing, we found three bedrooms. Like downstairs, all the rooms had unfitted lino. The two larger bedrooms still had their original furniture.

Bedroom 1: 14′10 × 9′ [4.5 × 2.7 m] into alcoves plus bay window to front, central tiled fireplace, picture rail. We went first into the master bedroom, the largest room in the house, situated at the front. There was a small, pretty double bed with a wooden headboard decorated with carved stylised flowers. A Queen Anne style dressing table with bowed cabriole legs sat in the front bay. The right-hand side of the bedroom extended over the staircase, giving room for a wardrobe. There was more space for furniture in the alcoves on either side of the fireplace. The fireplace consisted of a cast iron insert in an Art Nouveau style with elongated stylised flowers, more typical of the design of twenty years before the house was built. I wondered if this was leftover builders’ stock, or did fireplaces keep being produced in this style because they were popular?

Bedroom 2: 10′11 × 10′2 [3.3 × 3.1 m] into alcoves, central fireplace, picture rail. Moving into the second bedroom at the rear of the house, we found a smaller, metal fireplace insert with geometric chequered decoration. It had a portcullis-patterned, solid grid designed for a gas supply rather than an opening.

Bedroom 3: 7′2 × 6′7 [2.2 × 2m]. With cupboard housing hot water cylinder in one corner. Also at the rear of the house was a tiny box room. Suitable for a baby, I noted with great longing. The airing cupboard dominated the space. There and then I decided that it would have to go.

I was totally smitten with the house. As a former curator at the Victoria and Albert Museum, I pictured it as a series of period rooms that I could restore. Plus, over the last five years I had been immersed in the archives of the 1920s and 1930s Ideal Home exhibitions, along with trade catalogues, household advice manuals, memoirs, novels and films of the period for my recently completed PhD research.5 Like the heroines of the ‘middlebrow’ domestic novels that I had read, I was newly married, seriously broody and keen to set up home.6

I knew from the estate agent’s details that the house was built in 1934, which seemed an especially good omen as it was my favourite year of the Ideal Home Exhibition. My subsequent research revealed that it was built by the local builder Hinkins and Frewin.7 The house was in one of three streets of speculatively built houses in Lower Wolvercote aimed at the better-paid workers of the Oxford University Press paper mill situated nearby. In its layout and compact dimensions, it was quite typical of the modest houses built in the interwar years. The downstairs bathroom saved money on plumbing. I later found out that the lean-to kitchen was a later addition. The third bedroom was very small. Such modest houses, which sprang up in increasing numbers when mortgage conditions became more favourable after 1932, were intended to appeal to the better-off working classes and lower middle classes.8 In the 1930s houses on Oxford’s speculatively built estates typically sold for less than £525. Because of the demand from motor workers, they were priced higher than in most other parts of the country outside London, where prices averaged between £400 and £500.9 For paper mill workers who could not stretch to home ownership but could afford the rent, the alternative was the red-brick, cottage-style, local authority houses in short terraces built in the 1930s in Upper Wolvercote, separated from Lower Wolvercote by the canal and railway line.

The estate agent told us that the house was a ‘deceased estate’. Leaving the house, we stopped to chat to the next-door-but-one neighbours, who introduced themselves as Eddie and Nicky Clarke and their two sons James and Adam. Nicky told us that number 17 had been owned by her recently deceased grandmother, Cecilia Collett, who had lived into her nineties. Nicky’s grandfather, a worker at the Wolvercote paper mill on a modest wage, had purchased the house when it was newly built. He died in the 1960s, which explained why the house had remained largely unmodernised.

It turned out that the newly built number 17 Rosamund Road was purchased around 1934–35 by Vernon Victor Collett (1900–60) and his wife Cecilia (née Wells, 1897–1995). They moved into the house with their sons Basil, aged about 13, and Roy, aged about 10.10 Between 1840 and 1918 Colletts made up 483 out of the 1,074 surnames found in the parish registers.11 Both Vernon and Cecilia were from solid working-class backgrounds. Vernon was the third of six children of Percy Thomas Collett (1877–1948) and Gertrude Hall (1877–1967). The Colletts were a well-known family of stonemasons (an occupation carried out by Percy’s father) but Percy had broken with the family tradition and worked as a dairyman. Gertrude had worked in domestic service before her marriage and was the daughter of an innkeeper. Cecilia was the fourth of five children of Harry Wells (1860–1910), a house builder (formerly a tallow boiler and labourer), and Sarah Ellen Cox (1859–1951), daughter of a journeyman plasterer. After Sarah was widowed in 1910 she worked as a charwoman to support her family.12 Nicky told me that in purchasing number 17, Vernon Collett became the first person in his family to own his own home. The Colletts had only two children, in contrast to their own families of six and seven children. The small family of two or three children was typical of the respectable working and aspiring lower middle classes in the interwar years who sought to improve their standard of living, and was also dictated by the size and number of bedrooms in the typical interwar semi.13

That first visit to 17 Rosamund Road in 1995 was a catal...