![]()

1

Beyond the veil: sensing death in symbolist theatre

Picture something, if you will. It is the early 1890s, and you are attending a performance of symbolist drama in Paris, presented by Paul Fort’s Théâtre d’Art. A gauze scrim has been placed behind the footlights, veiling the stage. This material object dematerialises the scene of performance, casting it in a mysterious, murky light. The scrim makes the actors resemble shades. From your perspective, the actors are beyond the veil; figuratively, they are ‘beyond’ the mortal world. You are intrigued and captivated. You sense something larger-than-life, something otherworldly …

The phrase ‘beyond the veil’ is biblical in origin. In Exodus, instructions are given for the use of a piece of precious cloth to separate the innermost sanctuary, which contained the divine presence, from the rest of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. The Gospel of Matthew notes how the veil of the temple was ‘rent in twain from the top to the bottom’ upon Jesus’s death (27:51). A veil erected in a place of ritual, such as a temple or a theatre, therefore has mystical connotations, which the symbolists were keen to exploit. Many symbolists sought ‘to catch some far-off glimpse of that spirit which we call Death’, to quote Edward Gordon Craig, who had links with this movement (1911: 74). Disaffected with what they perceived as drab, enervating reality, symbolists sought spiritual rejuvenation in imaginary, mythological realms that could be intuited by artful arrangement (or derangement) of the senses and by veiling the scene of performance.

It is little wonder that death was a favourite theme of the symbolists, who evoked it in a range of art-forms, including theatre. In the fin de siècle, spiritualism was in vogue, and so the subjects of mortality and the afterlife were addressed with renewed interest. Spiritualists claimed to be able to contact the dead, thus proving that death did not mean the end of life but simply marked a transformation from a corporeal to a non-corporeal state of being. Scientists endeavoured to ascertain if there was any truth to spiritualists’ supposed abilities to contact the dead. In this way, the meaning of death was contested and put into flux. Symbolists tapped into these metaphysical concerns and called attention to the ambivalent presence of the dead in everyday life. Death haunts their art, and theatre provided a way for them to test out their ideas about that which lies ‘beyond the veil’.

This chapter explores cultural fascination with death in the fin de siècle. I outline how symbolist dramaturgy and mise-en-scène made it possible to ‘admit’ death as paradoxical presence in theatre – as something that could be sensed but not readily defined or contained. Audiences of symbolist theatre were invited to perceive death not only in embodied form as a personified character but as a stage presence, as something that could be sensorially detected, like a spirit in a séance, though with terror and uncertainty in lieu of spiritual assurance. I theorise how the symbolists marshalled the power of theatrical atmosphere to help them achieve this end. This chapter primarily concerns symbolist drama written in the 1890s and the early twentieth century, relating it to bohemian culture and social anxieties. Short plays discussed include Rachilde’s Madame La Mort (Madame Death, 1891), Charles van Lerberghe’s Les flaireurs (The Night-Comers, 1889), Maurice Maeterlinck’s L’intruse (The Intruder, 1890), and Leonid Andreyev’s Requiem (1916). The chapter ends with an analysis of W.B. Yeats’s symbolist-inspired play Purgatory (1938). Yeats titled his 1922 autobiographical work The Trembling of the Veil after a statement made by the symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé in the 1890s. Mallarmé, in Yeats’s words, said his epoch was ‘troubled by the trembling of the veil of the temple’ (1922: v). What might this mean? This chapter investigates the ‘trembling of the veil’ made by these deathly plays on the page and in performance. But first, let’s go on a jaunt.

The cabaret of nothingness

One of the curiosities of the red-light district of Paris in the fin de siècle was the Cabaret du Néant (the Cabaret of Nothingness), situated at 34 Boulevard de Clichy in Montmartre. Founded in 1892 by a magician called Dorville, the Cabaret du Néant was one of three death-themed venues he operated. The other two were the grandiosely titled Cabaret du Ciel (Cabaret of Heaven) and the Cabaret de l’Enfer (Cabaret of Hell), located on the same street as the Cabaret du Néant.

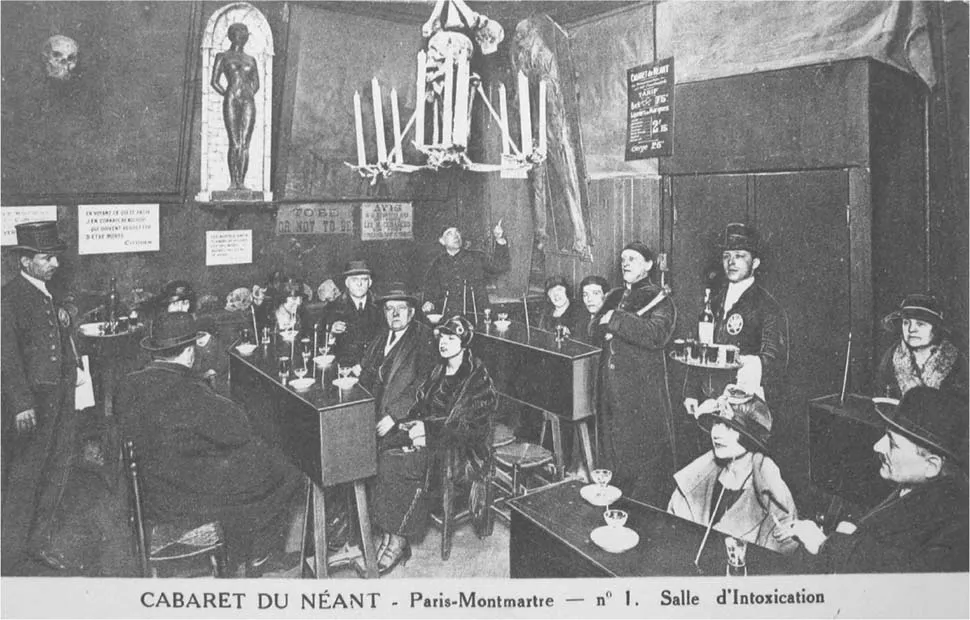

An evocative account of these cabarets is provided in a work of tourist literature from the period entitled Bohemian Paris of To-day, written by American author W.C. Morrow (based on notes by Edouard Cucuel). Morrow ostensibly relates Cucuel’s experiences as an American art student living in Paris. In the penultimate chapter, Cucuel and his friend Bishop take a visiting American writer, A. Herbert Thompkins, for a night out on the town. Instead of going to the opera, as Thompkins expects, Cucuel and Bishop take him to Montmartre on a ‘tour of discovery’, intending to ‘introduce him to certain things of which he might otherwise die in ignorance, to the eternal undevelopment [sic] of his soul’ (1899: 253, 251). Following an uplifting visit to the Cabaret of Heaven, which features a man dressed as Dante, a lantern projection of St Peter’s head, a bevy of gyrating angels, and a shrine containing an immense golden pig, the pair lead Mr Thompkins to the Cabaret du Néant. The entrance is draped with black cerements with white trimmings, like that which ‘hang before the houses of the dead in Paris’ (ibid.: 364). Patrolling it is a solitary pallbearer with a black cape and top hat. Inside, the trio find a chamber dimly lit by wax tapers and a chandelier made of human skulls attached to bones clutching candles. Wooden coffins, resting on biers, are ranged about the room (see Figure 1.1). The walls are decorated with skeletons in grotesque attitudes, battle pictures, and guillotines in action. The trio, noting what appears to be the distinct odour of a charnel house, find an empty coffin-table and order drinks from a garçon dressed in the garb of a hearse-follower. They sit in the cabaret’s gloomy atmosphere for a while. Thereafter, the master of ceremonies invites the guests to enter a passage lined with bones, skulls, and fragments of human bodies, at the end of which is the chambre de la mort. Inside, they are seated upon rows of small caskets and behold an upright, coffin-shaped opening in the wall (see Figure 1.2). Presently, a greenish-white light illuminates the coffin-shaped hole, revealing a young woman robed in a white shroud. She smiles at the audience and looks at them saucily. Her smile soon fades as a voice from the depths charges her to compose her soul for the end. A grisly transformation occurs. Morrow details the macabre spectacle:

Her face slowly became white and rigid; her eyes sank; her lips tightened across her teeth; her cheeks took on the hollowness of death – she was dead. But it did not end with that. From white the face slowly grew livid … then purplish black. … The eyes visibly shrank into their greenish-yellow sockets. … Slowly the hair fell away. … The nose melted away into a purple putrid spot. The whole face became a semi-liquid mass of corruption. Presently all this had disappeared, and a gleaming skull shone where so recently had been the handsome face of a woman; naked teeth grinned inanely and savagely where rosy lips had so recently smiled. Even the shroud had gradually disappeared, and an entire skeleton stood revealed in the coffin. (ibid.: 272)

1.1 Postcard of the ‘intoxication room’ at the Cabaret du Néant, Paris, c. 1900. Note the coffin-tables and the skull-and-bones chandelier. One of the signs on the wall says ‘To be or not to be’.

But the show isn’t over yet. The voice in the darkness addresses the skeleton, informing the audience that death is not final for everyone: ‘The power is given to those who merit it, not only to return to life but to return in any form and station preferred to the old’ (ibid.). The young woman is bid to return if she thinks she deserves to, and if she wishes. Lo and behold, the process of bodily decay slowly reverses and the skeleton becomes a living person again – but not the young woman of before. Instead, the rotund body of a banker appears in her place. He promptly steps out from the coffin-shaped hole in the wall, to the audience’s amusement. The trio later exit and set out to visit the cabaret of hell. Mr Thompkins, the narrator notes, ‘seemed too weak, or unresisting, or apathetic to protest. His face betrayed a queer mixture of emotions, part suffering, part revulsion, part a sort of desperate eagerness for more’ (ibid., 276, 279).

1.2 Postcard of the ‘vault of the dead’ at the Cabaret du Néant, Paris, c. 1900

The attraction/revulsion felt by Mr Thompkins is presumably what enticed patrons to the Cabaret du Néant. The cabaret offered patrons a morbidly amusing, potentially unnerving social entertainment capped with techno-wizardry; the schlock factor was likely a draw as well. Picture postcards corroborate Morrow’s account of the cabaret’s distinguishing features and unique selling points. The cabaret was overloaded with deathly signifiers, which furnish Morrow’s thick description. It is hard to imagine patrons taking the cabaret’s offerings seriously. However, despite its gore, the cabaret provided an oddly comforting take on death, courtesy of the stage illusion at the end. Patrons could enact a sped-up version of their own final bodily decay. (What fun, eh?) They could imaginatively and performatively undergo transformation into a corpse and then ‘magically’ be restored to their former selves (via a Pepper’s Ghost-type effect involving canny lighting and a second, hidden coffin complete with skeleton, shown via a glass reflection). Those attending could witness a person’s ‘death’ and know this event did not necessarily mark the end of life, but rather foreshadowed possible reincarnation. Conceivably, the repetition of this trick could have made death seem less frightening, despite the surface horror of ‘corpsification’.1 The cabaret sought to unnerve and console patrons – a good business strategy.

The Cabaret du Néant was not the only venue that provided spectacles of death in 1890s Paris. Oscar Méténier founded the Théâtre du Grand-Guignol in 1897, inspired by the naturalist aesthetic of the Théâtre Libre. The Grand-Guignol, also located in the Pigalle area of Montmartre, offered audiences a ‘slice of death’ – a counterpart to the naturalists’ ‘slice of life’ – in presentations of heightened horror (throat-slitting, beheading, and the like), reportedly causing audience members to become nauseous or lose consciousness (Hand, 2010: 73).2 Nor were Parisians restricted to stage renderings of mutilation, death, and decay. They could observe actual human corpses at the Paris Morgue, which was purpose-built to allow public viewing of unidentified dead bodies. The morgue became a tourist attraction, receiving up to ten thousand visitors per day (Kosmos, 2014: 464). Additionally, the Catacombs of Paris, opened to the public on a regular basis in 1874, allowed access to the remains of an estimated six million people contained in its ossuaries (ibid.: 465). In the late nineteenth century, when symbolist theatre emerged, the subject of death was hardly taboo. Quite the opposite: in Paris, death was an object of fascination; there was an appetite for death-themed attractions. However, some cultural commentators thought this morbid sensibility was indicative of widespread cultural decadence and social decline.

Degeneration

The Hungarian-born social critic Max Nordau was one of the principal architects of this vision. Nordau’s book Degeneration, first published in 1892, is a sprawling, venomous denunciation of the fin de siècle and the artwork it inspired. The book caused a sensation upon its release, as well as strident backlash and criticism. Nordau contended that rich inhabitants of great cities and certain types of modern artists were social degenerates who were contributing to the decline of humanity by their morose dispositions and moronic activities. Nordau diagnosed the spirit of the age as being weak and sickly, in a state of nervous exhaustion, overcome by malaise, and in love with death. The mood of the fin de siècle, he writes, is ‘the impotent despair of a sick man, who feels himself dying by inches in the midst of an eternally living nature blooming insolently for ever’ (1993: 3). Nordau believed an unhealthy, defective subset of humanity was responsible for the temperamental funk he poetically calls the ‘Dusk of the Nations’ (ibid.: 6). Degenerates, in Nordau’s estimation, crave fads and sensations, or else they are overwhelmed by sensation and indulge in melancholia. They are weak-willed, mentally deficient, aimless, unable to concentrate, overemotional, and hysterical. They are fatigued and incapable of doing work or bonding with their brethren in a common cause. (I know the feeling.) They are fearful of the world around them and the unknown spectres it contains. They are predisposed to reverie and easily become entranced with specious mysticism and fuzzy thinking. They are to be pitied and disdained, these mental drifters. (Reader: focus.) Nordau suspects that modern urban life is responsible for increased signs of degeneracy in culture and society. He writes:

The inhabitant of a large town, even the richest, who is surrounded by the greatest luxury, is continually exposed to unfavourable influences which diminish his vital powers far more than what is inevitable. He breathes an atmosphere charged with organic detritus; he eats stale, contaminated adulterated food; he feels himself in a state of constant nervous excitement (ibid.: 35).

Following Nordau’s spook-train of thought, is it any wonder that world-weary Parisians would seek such morbid pleasures as the Cabaret du Néant?

Nordau gets out his rhetorical knives for the exemplars of social degeneracy and cultural decadence, which are legion, in his opinion. Mysticism is one of his chief bugbears. He lambastes exponents of a state of mind ‘in which a man fancies that he perceives inexplicable relationships between distinct phenomena and ambiguous formless shadows’ (ibid.: 57). Nordau explains mysticism as the result of weakness of will and incapacity to organise thoughts in an orderly, rational manner. Unsurprisingly, Nordau derides symbolist artists and the work they produce. He contends they show ...