![]()

part 1

• Narrative Distance and Narrative Voice

dp n="17" folio="" ?dp n="18" folio="3" ? ![]()

FREDERICK REIKEN

The Author-Narrator-Character Merge: Why Many First-Time Novelists Wind Up with Flat, Uninteresting Protagonists

During my years in an MFA fiction writing program, I wrote a novel that was never published. It was not for lack of trying, as I radically rewrote it three or four times during the course of those three years, made one more attempt the year after I finished the program, and showed it to half a dozen literary agents before finally putting it in a drawer and moving on. I now consider it the novel I had to write in order to teach myself how to write a novel, and soon after I let it go it became obvious that the novel shouldn’t be published, though it has taken me many years to determine why.

The material for the novel was derived from my year working as a field biologist in Israel’s Negev Desert, studying Persian onagers, a species of wild ass that had recently been introduced into the Israeli desert wilderness. I faced many interesting conflicts, including drug smugglers and terrorists routinely passing through the desert crater that formed the study area, as well as onagers that sometimes crossed into Jordan, where they were usually shot by Jordanian border patrols. Some of the animals wore radio collars, and one night the Jordanian TV news ran a story claiming that soldiers had shot a trained Israeli donkey carrying a bomb. After a while it dawned on me that what I was living through seemed a lot like fiction.

dp n="19" folio="4" ?I started an MFA program at the University of California at Irvine about a month after I returned from Israel, and my adviser there was instantly in love with my idea for a novel that featured a young American biologist studying wild asses in Israel. I was twenty-three and had written a dozen or so short stories, perhaps three of which had any substance whatsoever. But I plunged in with the standard mixture of idealism and egomania, believing my adviser’s promise that if I wrote this book I’d soon be the next twenty-five-year-old literary star. My writing models were limited, but I immersed myself in a study of classic literature, one result of which was that my writing tended to emulate whoever I’d been reading. In the first draft of that novel—with working titles ranging from The Land of Solomon to Wild Ass Mirage—sections read alternately like Virginia Woolf, Gabriel García Márquez, William Faulkner, and James Joyce. The second draft was so derivative of Joyce that one of my friends joked that I should change the title of the novel to U-asses. In hindsight, emulating these authors was a valuable step in the formation of my own voice, but only two years later did I become conscious of what I was doing. I recall deciding that if I wrote a second novel, I would have to invent a voice that would, paradoxically, sound like me.

More significant than the pastiche of style, however, was the fact that there was no distinct story, which in turn was linked to the fact that all three point-of-view characters in this third-person narrative were quite passive, serving as observers of the action around them but rarely becoming dramatic focal points themselves. I’d written a kaleidoscopic portrait of an idealized small desert town where biologists studied wild asses and female soldiers fell in love with biologists, against the backdrop of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, which had started while I was there. I tried and tried to make the characters more interesting and alive, and though they were somewhat improved in successive drafts, the whole thing never came together. Many readers, agents included, had similar comments—which I’ll sum up this way: “The writing is really great, some of the scenes in the desert very beautiful, and I love all the descriptions of wild asses. But I was bored and uninterested in the characters. It’s almost like you’re not seeing them.”

dp n="20" folio="5" ?When I wrote my first published novel, The Odd Sea, I was relieved to have solved this problem. At the time, I chalked it up to learning the art of restraint through working as a journalist for several years. Then in 1999 I began teaching at Emerson College, and in my first semester I taught a graduate workshop in novel writing. The student novels ranged in topic from a woman grappling with a rare body disorder to a young man whose MIA father returns from Vietnam in the 1980s, to a woman searching for family secrets in Northern Ireland. In my mind, all of these story conceptions had tremendous potential, but in each case my main reactions were: 1) I was bored and uninterested in the characters, and 2) it seemed as if the author wasn’t seeing them. I have now taught this novel course every fall since then, and at least half of the novels I wind up seeing share this problem. My first reaction was that most novelists needed to go through this, to do what I did—spend years writing a failed novel that would teach them how to write a successful one—and I would still say this is true. Most would agree that Stephen Hero, Joyce’s first version of what would later become A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, is almost unreadable, and that The Voyage Out was similarly a novel Woolf had to write in order to teach herself what she didn’t want to write.

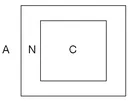

During my second year at Emerson I had my first glimpses of understanding about why so many first novels by MFA students, particularly those that are autobiographical in some way, are, in a word, flat. When I say it feels as if the author isn’t really seeing the characters, I am talking about the particular flatness that comes from what I call the author-narrator-character, or ANC, merge.

At its simplest, the merge may be thought of as the narrative structure that occurs when an author, for reasons ranging from naïveté to authorial narcissism (which often go hand-in-hand), fails to invent and/or reinvent—in the case of autobiographical novels—the main character, both visually and in relation to some objective external context. The author has not separated him- or herself imaginatively from the character—has not conceived the fictional construct as an other—and is in effect stuck inside the character, usually right behind the character’s two eyes. What typically results is a narrative in which there is virtually no distance between the story’s narrator and character, and a sense that the main character is nothing more than a narrating device—and hence not much of a character at all. Most aspiring novelists are aware of this phenomenon—the first-person narrator or third-person point-of-view character as passive observer—and it’s my sense that a problematically passive protagonist is often, though not always, a merged one. With a merged narrator and character, both are neutralized. Not only is there a flat character; there is also no narrating apparatus to cue us on the logic of the story flow—that is, no apparatus for translation of what’s going on dramatically—and hence no perspective, texture, or depth, and frequently a complete lack of narrative voice.

Separating Author, Narrator, and Character

Before this can make much sense, we must be able to delineate instinctively between the three domains of author, narrator, and character, which is not as simple as it sounds. For one thing, we often mistake the narrator or even the character for the author. Strictly speaking, an author is a human being who exists outside the novel’s textual universe. (Under this strict definition, the same would hold true even in the case of nonfiction memoir.) The author is, of course, the book’s prime mover, but as a biological creature the author can never physically enter the textual dimension and hence is limited to a presence that depends on the level of symbolic correspondence between the author and his or her textual components—the narrator(s) and character(s). Some theorists have even claimed that a novel’s power rests with the paradox that an author asserts his or her presence through a form of absence.

Meanwhile the narrator, strictly speaking, is a construct of language, invented for the purpose of both presenting and translating the novel’s action such that a reader can stay oriented with the narrative’s sentence-by-sentence flow. Every thought, gesture, or action—indeed, every absence of thought, gesture, or action—falls under the narrator’s jurisdiction, as do the mechanics of the writing, right down to choices of punctuation. Obviously the author makes these decisions, but they are presented via the narrator, who governs the textual universe and shapes our relationship with the characters, who are, of course, the focus of a conventional, storyoriented literary novel. The ANC structure can be represented as a series of so-called Chinese boxes, in which the narrator’s domain subsumes that of character and the author’s domain subsumes those of both narrator and character:

Let us first consider the case of a first-person narrative. One might immediately suggest that when the narrator is also the book’s protagonist, there is no distinction to be made between narrator and character. To which I would say: Wrong. I’d go so far as to argue that the key to a successfully executed first-person novel usually lies precisely in the relationship between that first person as narrator and as character. Consider Holden Caulfield in the opening passage of J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye.

If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you’ll want to know is where I was born, and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth. In the first place, that stuff bores me, and in the second place, my parents would have about two hemorrhages apiece if I told anything pretty personal about them. They’re quite touchy about anything like that, especially my father. They’re nice and all—I’m not saying that—but they’re also touchy as hell. Besides, I’m not going to tell you my whole autobiography or anything. I’ll just tell you about this madman stuff that happened to me around last Christmas just before I got pretty run-down and had to come out here and take it easy. (1)

As we learn, the book is structured as a story in which Holden—who is now “out here,” in a place that lies beyond the time line of the story’s dramatic action—is looking back at “all this madman stuff” that occurred during a period of days in the previous year. In other words, there is an implied separation between where Holden sits as narrator and the time frame he occupies as a character. In this opening we are with him in the expository domain of Holden as narrator, but within a page or so, as is the case with most novels, we enter the domain in which Holden begins to look at himself as a dramatically oriented character. In this case the transition occurs in the novel’s third paragraph: “Anyway, it was the Saturday of the big football game with Saxon Hall. The game with Saxon Hall was supposed to be a very big deal around Pencey. It was the last game of the year, and you were supposed to commit suicide or something if old Pencey didn’t win. I remember around three o’clock that afternoon I was standing way the hell up on top of Thomsen Hill, right next to this crazy cannon that was in the Revolutionary War and all” (2).

Here Holden establishes the real-time setting and the ground situation of the story and then places himself, as a character, on top of Thomsen Hill. As the passage continues he moves back and forth between the character domain and the narrator domain, which orients the story. By page 4, he reaches a point where the dramatic or character mode becomes predominant. Note that Holden’s strong narrative voice greatly assists in this movement. It is a perfect example of how useful the rhetorical effect of a strong first-person voice is in allowing the narrator to move effortlessly between the character domain, in which the story is rendered, and the narrator domain, in which the story’s action is translated, commented upon, and placed in the larger context of the character’s life trajectory. The voice also helps to characterize Holden, even when he is speaking within the domain of narrator. Part of the power of strong voice-driven fiction comes out of this synergistic effect.

Many first-person narratives I have read by beginning novelists never visualize or establish the first-person narrator as a physically placed character—that is, envisioned in a sequence of temporally contextualized, dramatically evolving scenes. The narrator spends an inordinate amount of time reflecting internally—that is, “navelgazing”—and the action that does occur is presented in relation to other characters or is simply summarized rather than dramatized in relation to the protagonist/narrator. Within the author’s imagination, I believe, the author, narrator, and character are perceived as synonymous rather than being structured as separate domains. The result can be an almost essaylike compression of the three. This happens in intentionally autobiographical material as well as completely invented material, although in such cases there are usually similarities between author and protagonist or at least subtle autobiographical associations.

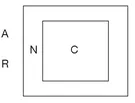

With Holden, we can also consider how the author-narrator-character relationship sets up the effect created by a limited or unreliable first-person perspective. Holden, of course, is absolutely clear on the veracity, legitimacy, and logic of his every thought or action, and this is made clear in the relationship between Holden-as-narrator and Holden-as-character. The relationship, however, of author Salinger to narrator/character Holden is quite different from that of Holden-as-narrator to Holden-as-character, and the result is a dialectic in which these two relationships interact and in which we, as readers, are situated next to the author:

Salinger’s perception of Holden objectively renders him as lost, confused, and disoriented, even as Holden is telling us otherwise, and the pathos we feel is largely tied to the rift between what we and Salinger see objectively and what narrator Holden, in his desperation, perceives with regard to his own odyssey. If we think about certain exquisitely rendered unreliable first-person narratives— Eudora Welty’s story “Why I Live at the P.O.” or Kazuo Ishiguro’s novel The Remains of the Day, for example—we can instantly see this effect. And if we think about the ANC relationship, we come to realize that in addition to whatever dramatic tension is occurring, we are equally riveted by a different kind of narrative tension that arises from the rift between the author’s objective rendering of a character and that character’s limited perception of what’s going on. It’s also worth noting that the power of well-executed metafiction is tied to a similar strain of narrative tension, derived from a manipulation of the ANC relationship such that a character takes on the awareness of a narrator or author, or in which the author pretends to be a character.

Though I will not dwell on it here, I want to point out that even in the special case of a first-person present-tense narrative—a point-of-view choice that, because there is no implicit temporal gap between narrator and character, relies on high artifice—there is still a clear separation between narrator and character in successful story-oriented narratives. Usually this is because the artificiality of the tense actually does allow for a temporal gap, though it may be a gap of seconds rather than years and it is usually combined with a subtly metafictional narrative objectivity (that is, the character can shift between the domains of narrator and character much like Holden Caulfield, even though this degree of instant reflective clarity would be impossible in real life). Often a great deal of narrative space is devoted to flashbacks that get presented in the past tense. Without a successful separation, a first-person present-tense narrative tends to become a stream of impressionistic minutiae that may engage on the basis of tone for a short while but that will soon lapse into annoying stylistic pretension. Or, as in the case of the following anonymous student example, it may result in a narrator and character being merged to the extent that we can barely tell what’s happening:

The warmth from his hand passes through my eyelids and into the tired sockets encasing two spheres with ocean-blue enigmas, as he had called them. I attempt to place my hand upon his, desperate to feel his touch again, only to find nothing. Frantically tossing the comforter from my shirtless torso, I open my eyes to scan the room. The bureau we found on the street stands regally in the corner leaving enough space to hide behind. This could all be a cruel trick.

Moving on to third-person narratives, the distinction between narrator and character is, on the one hand, obvious, as the narrator is not embodied in the storyline. However, I have found ANC merges to be more common in third-person than in first-person narratives, and in several cases students have solved the merge problem by switching to a first-person past-tense point of view, where a natural split occurs between the future place from which the narrator is reflecting and the timeline of the character moving through the story. With a third-person point of view, the sense of where the narrator is in relation to the story can get a lot fuzzier, since the narrator is not situated in time. In order to consider the position of a third-person narrator, a useful distinction can be made with regard to what John Gardner, in

The Art of Fiction, refers to as the psychic distance between narrator and character. He offers these five examples, in order of progressively diminishing psychic distance:

1. It was winter of the year 1853. A large man stepped out of the doorway.

2. Henry J. Warbutton had never much cared for snowstorms.

3. Henry hated snowstorms.

4. God how he hated these damn snowstorms.

5. Snow. Under your collar, down inside your shoes, freezing and plugging up your miserable soul. (111)

In example 1, we have the third-person narrator looking at an unnamed man with great psychic distance. This is the type of longrange psychic distance you might expect at the opening of a novel. In example 2, we are getting situated in the character’s point of view, but we still hear the oral quality of the narrator, who is orienting what seems more likely to be the beginning of a short story. In example 3, this “voice-over” quality of the narrator drops off, and as a result we no longer see the character; rather, we are situated inside the character’s head, privy to his perceptions but no longer looking at him from the outside. In example 4, Gardner makes use of a technique known as free indirect discourse, through which the character’s thoughts are subsumed by the narrator. In example 5, we get stream-of-consciousness interior monologue, which is technically a variety of free indirect discourse.

Most third-person narratives proceed with constant modulation of the psychic distance, moving like a camera eye between longrange establishing shots and very limited, close-range character point of view, and then back out to longer-range shots again. But in a case in which the author has not fully imagined the point-of-view character—often because the author has not yet truly conceived the character as a bona fide other—the ANC relationship gets structured so that there is little or no psychic distance between narr...