![]()

Part 1

The Forests and Their Trees

What is a Forest Tree?

With rare exceptions, a tree is considered here to be a perennial, self-supporting woody plant, typically with a single main stem or trunk, a distinct crown and capable of growing to a height of at least five metres. Trees grade physiognomically into large shrubs. A few species on the borderline between trees and shrubs have been included in this field guide, providing useful information for readers trying to distinguish them from those similar-looking plants that are clearly small trees.

The term ‘forest’, as used here, refers to a type of vegetation that typically has a continuous stand of trees, a tall canopy (10 to 50 m or more) and usually several layers of trees with crowns interdigitating with one another or overlapping (Fig. 1.1) (McElhinny et al. 2005; Obua et al. 2010; Côte et al. 2018; FAO 2018a, 2018d). It is a type of vegetation that regenerates naturally to maintain a complex structure (Kalema and Kasenene 2007; FAO 2018a, 2018d). Also known as tropical rainforest or, in Uganda, as Tropical High Forest, forest contrasts with certain other types of vegetation that are similarly dominated by trees and that are normally known by scientists concerned specifically with Ugandan vegetation as woodland (Langdale-Brown et al. 1964; White 1983). Woodland can usually be distinguished from forest in having only a single tree layer, an abundance of narrow-leaved grasses in the herbaceous layer (not the broad-leaved grasses common in some forests) and in being subject (and adapted) to burning. Also excluded are those other types of vegetation found in Uganda dominated by woody plants known scientifically as thicket and evergreen scrub. Forest becomes reduced in stature at high altitudes, with fewer tree layers, and, above the limit of broad-leaved trees, can grade into vegetation dominated by microphyllous trees (typical of the Ericaceous Belt) and giant groundsels (typical of the Afroalpine Belt). We have included trees found in these two vegetation belts here.

Confusingly, the term ‘forest’ is sometimes applied to other types of Ugandan vegetation apart from forest as we understand it. This means that reports on the state of Ugandan forests need to be read cautiously. The definition of forest, as used by the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity (2001) defines forest as including types of ‘ecosystems in which trees are the predominant life forms’, which is a very broad definition meant to cover global variations.

Vegetation on the boundary between forest and other forms of vegetation is in an intermediate situation and its flora can be distinctive (Fig. 1.2) (Marfo et al. 2019). This zone with its abrupt to gradual change in species composition is associated with changes in other aspects of the environment, such as climate, soils and human use of natural resources (Liautaud et al. 2019), but the extent to which the position of the boundary is a consequence of these other factors or these other factors are responsible for the position of the forest can be difficult to judge (Brownstein et al. 2015). The type of ecosystem found on one side of the boundary can have profound influence on that on the other and the boundary itself (an ecozone) can be more biologically diverse in terms of numbers of species than the areas on either side (Hufkens et al. 2009; Marfo et al. 2018). We include here the commoner species of trees found in boundary zones and on forest edges, but omit those seen less frequently.

Fig. 1.1. Forest structure of Mpanga Central Forest Reserve, a lowland semi-deciduous forest of the Lake Victoria forest belt. Photo: Alan Hamilton (2019).

In an earlier field guide to Ugandan forest trees (Hamilton 1981), which was based on reports and observations made prior to 1972, it was stated that ‘there is rarely any difficulty in determining whether or not a certain type of vegetation is forest, since marginal types of vegetation have been almost completely eliminated by burning, grazing and agriculture over a long period of time. Indeed, the boundaries of the great majority of forests are artificial and, in many cases follow Forest Department demarcation lines [our emphasis]’. This is no longer so true.

Many forests have been and continue to be degraded through human activities (Kalema et al. 2010), even in protected areas (Sassen and Sheil 2013). There has been widespread land use and land cover change (Kalema and Bukenya-Ziraba 2005; Kyarikunda et al. 2017). Extensive areas of ground now contain a mixture of forest and non-forest species. Sometimes, the clearance of forest to plant crops results in the leaving behind of impoverished ecosystems with only a few scattered tall trees (Fig. 1.3). It can be predicated that many of these trees, now abandoned to the elements, will soon die. This degradation and loss continue despite enactment of a National Forestry and Tree Planting Act (Government of Uganda 2003) and new institutional arrangements. The latter include establishment of a Forest Sector Support Department, the National Forestry Authority (NFA) and District Forestry Services (Tumushabe and Mugyenyi 2017; Josephat 2018).

Fig. 1.2. Boundary of Mpanga Central Forest Reserve. Photo: John Kalule (2019).

Forest Distribution and Types in Uganda

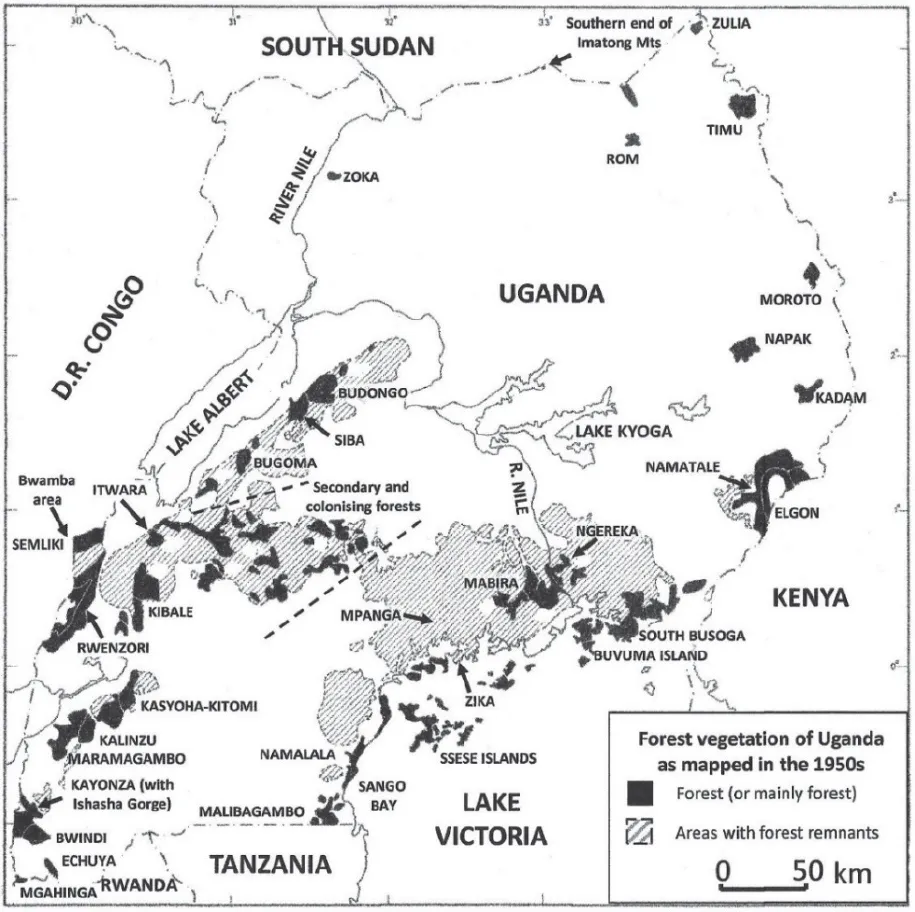

Figure 1.4 shows the distribution of larger areas of forest in the 1950s, based on a map in Government of Uganda (1967). Also shown are those parts of Uganda that would naturally have carried forest before its clearance by people (estimated from a combination of climatic parameters and the presence of forest remnants). It can be seen that many of the forests lie in two regions, both of which are characterized by relatively high and well distributed rainfall. One is to the north of Lake Victoria (the lake belt) and the other, lying on or close to the border with D.R. Congo, is associated with the Albertine Rift. The forests shown in north-eastern Uganda (Kadam, Timu, etc.) are on mountains. Groundwater sometimes sustains forest in climatically dry areas, as along river banks (riverine forest).

The floristic composition of the forests, which in turn contributes to their structure, is greatly influenced by temperature, which reduces with altitude (FAO 2017; Mau et al. 2018; Mujawamariya et al. 2018; Cabrera et al. 2019), as well as climatic moistness and environmental history (Hamilton 1989; Tang 2019). A standard system of classification used for forests in Uganda recognizes two principal altitudinal types, High Altitude (or montane) Forest above 5000 ft (1525 m) and Mid Altitude Moist Forest below (Langdale-Brown et al. 1964). Mid Altitude Moist Forest, especially that below 1400 m, is floristically akin to forests at much lower altitudes (towards sea level) elsewhere in tropical Africa (Hamilton 1989; White 1983) and can be alternatively referred to as lowland. All the lake-belt forests are lowland, while both lowland and montane forests can be found along the Albertine Rift. Lowland forest varies in species complement and physiognomy between wetter and drier areas, an increased proportion of deciduous trees being found in the latter *(semi-deciduous forest).

Fig. 1.3. Matiri Central Forest Reserve, severely damaged by encroachment for agriculture and felling trees for charcoal. Photo: James Kalema (2009).

If the total altitudinal ranges of tree species in the country as a whole are considered, then lowland and montane forests grade gradually into one another without an abrupt transition (Hamilton 1989). However, there are some species that can assume great abundance over particular altitudinal ranges, providing handy ways to classify the forests further. Mountain bamboo (Sinarundinaria alpina) tends to form extensive stands in climatically wetter areas at high elevation (normally 2450-3050 m), thereby enabling recognition of a moist lower altitude montane forest zone below (1500-2450 m) (also known as Pygeum [= Prunus] Moist Montane Forest) and an upper montane forest zone above (3050-3300 m) (also known as HageniaRapanea Moist Montane Forest) (Langdale-Brown et al. 1964). Cynometra alexandri and Parinari excelsa can be locally abundant in some of the Albertine Rift forests at altitudes of 700-1200 m and 1400-1500 m respectively.

Forest was restricted in distribution during the last global ice age, which was marked by a dry climate across much of tropical Africa (Hamilton et al. 2016). The climate became wetter 12,000 years ago, allowing many forest species to expand their ranges away from dry period forest refugia, including one in Kivu Province (eastern D.R. Congo). Species had different abilities to spread, the net result being for Uganda the creation of gradients of decreasing numbers of forest species away from the border with D.R. Congo, especially away from the south-west. This pattern is superimposed on other patterns considered to be caused by modern environmental factors, such as temperature and rainfall (Hamilton 1989; Howard 1991; Brack 2019; Tang 2019). It is predicted that modern anthropogenic climate change will further affect the forests (Lewis 2006). There are indications that tropical trees may be more vulnerable to continued warming than temperate species, as tropical trees have shown greater declines in growth and photosynthesis at elevated temperatures (Mau et al. 2018).

The richest forests in Uganda in terms of biodiversity, as measured by species scores for four taxonomic groups (one being forest trees), are Bwindi (Fig. 1.7) and Semliki (Howard 1991). Ishasha Gorge in Kayonza Forest (northern part of Bwindi) has a particularly diverse and unusual flora and could possibly have been the site of a minor forest refugium during the time of ice age aridity.

Some idea of the botanical diversity of the forests may be gauged from the numbers of tree and shrub species encountered in transect surveys through five of Uganda’s forests carried out for comparative biodiversity purposes (Howard 1991). The first number for each forest in the following list is the number of tree and shrub species classified as ‘belonging to the forest interior’ and the second for a wider ecological group of tree and shrub species ‘deemed to be forest dependent’: Budongo 123/233, Bwindi 106/188; Kalinzu 121/236; Kasyoha-Kitomi 120/226; Kibale 110/204; Semliki 108/199 (Davenport and Howard 1996; Davenport et al. 1996; Howard et al. 1996a-d).

Fig. 1.4. Distribution of forest in Uganda during the 1950s (Atlas of Uganda 1967).

There is much variation in the floristic composition of forest at the local level. Forests lying close to Lake Victoria within the lake belt (often developed on sandy soils) tend to have a distinctive tree flora, for example with an abundance of the large tree Piptadeniastrum africanum. They are known as lake-shore forests. Forests inland from Sango Bay (on the edge of Lake Victoria), some standing on swampy ground, are particularly unusual floristically, containing a number of typically montane trees, such as Afrocarpus dawei and Podocarpus latifolius. This may be the site of a minor forest refugium during the last ice age, a time when temperatures as well as rainfall were depressed. Possibly the forest was sustained by high levels of groundwater fed by a still active River Kagera.

More generally, forest composition varies everywhere according to position on slope, responding to catenary variations in soils and other environmental variables along gradients extending from hilltops to valley bottoms. Swampy ground has its particular trees. Both human activities and natural processes influence forest composition at the very local level. Forests are dynamic living systems, individual trees passing along pathways of establishment, growth, maturity and death. The falls of large trees create gaps in the forest canopy, triggering phases of new tree establishment and spurts of rapid growth on the part of trees already present. The dynamics of forest systems, such as this, have intimate influences on the exact positioning of individual trees on the ground.

Fig. 1.5. Making charcoal from indigenous forest trees in Mabira Central Forest Reserve. Photo: William Olupot (2018).

History of Human Influence on the Forests

Small-scale shifting agriculture within a forested environment started to have a significant influence on the local floristic composition of Ituri Forest (D.R. Congo) from the beginning of the first millennium CE (Hart et al. 1996) and the same is likely to have been the case in nearby Uganda. Shifting cultivation changes primary forest to secondary forest (Spracklen et al. 2018), which tends to be less diverse and structurally less complex. Probably all forests in Uganda have been influenced to at least some extent by the human hand, especially through previous clearance for agriculture (Hamilton et al. ...