![]()

CHAPTER ONE

TERMINAL CONNECTIONS

Utopian and one which, even if it could be accomplished, would certainly never pay … The whole idea has been gradually associated with plans for flying machines, warfare by balloons, tunnels under the channel and other bold but hazardous propositions of the same kind … an insult to common sense.

(The Times, 1861, referring to the Metropolitan Railway)

The line may be regarded as the great engineering triumph of the day.

(The Times, 1863, referring to the Metropolitan Railway)

THE METROPOLITAN RAILWAY

Plans for a sub-surface railway to provide a link between the City of London and main line stations to the north had been in existence for several years. The Great Western Railway was particularly concerned that Brunel’s terminus at Paddington, opened in 1838 on what was then the fringe of the built-up area, was too far from the City for its passengers’ convenience. In 1854 a bill was presented to Parliament, the cumbersome title of which reveals its purpose: ‘The Metropolitan Railway, Paddington and the Great Western Railway, the General Post Office, the London and North Western Railway and the Great Northern Railway.’ The plan, originally devised by a financier called William Malins, was to link Paddington, Euston and King’s Cross by a railway running beneath the Marylebone–Euston–Pentonville road, picking up passengers from each station. The inclusion of the General Post Office secured the support in Parliament of Rowland Hill MP, who in 1844 had invented the penny post. A former chairman of the Brighton Railway Company, Hill was an enthusiastic advocate of rail transport and was concerned about the delays to the post caused by London’s chronic traffic.

In 1854 a parliamentary committee considered the plan and, in particular, looked at the problems posed by steam engines in long underground tunnels. John Fowler, engineer to the projected line, had asked Robert Stephenson to design a locomotive that could run the length of the proposed railway on heat and steam built up in the open air before entering the tunnel. To reassure the committee Fowler produced as a witness Isambard Kingdom Brunel himself, who insouciantly declared, ‘I thought the impression had been exploded long since that railway tunnels require much ventilation’, adding, enigmatically, ‘If you are going a very short journey you need not take your dinner with you, or your corn for your horse’.1

Over the next four years the project underwent several changes of name, directors and route, the one constant factor being John Fowler, who remained the very well-paid consultant engineer to the company. By 1858 the Fowler Railway Project, its title mercifully shortened to the ‘Metropolitan Railway’, had in effect absorbed the plans for Pearson’s ‘Arcade Railway’ referred to in the introduction. It combined the two schemes into a single line beginning at Bishop’s Road, near Paddington, which would pick up passengers from stations at Edgware Road, Baker Street, Great Portland Street, Euston Square and King’s Cross before turning south along Pearson’s proposed route to Farringdon.2 There would be connections to the Great Western tracks at Paddington and the Great Northern tracks at King’s Cross, so that the underground line could accommodate trains from these railways as well as offering its own shuttle service. The presence of Great Western trains meant that the tracks had to be laid to accommodate the company’s broad gauge (7ft) rolling stock as well as the standard gauge (4ft 8½in) stock of the other services. There would also be a connection with the new Smithfield meat market for goods trains.

In 1858 The Times reported another meeting at the London Tavern, chaired by the Lord Mayor and addressed by Pearson and by Lord John Russell, MP for the City of London.3 Their speeches prompted much cheering and some bold resolutions, but this time they also produced some money. Earlier in the year, William Malins had been replaced as chairman of the Metropolitan Railway by the stockbroker William Wilkinson, who enjoyed good City connections. The time was right. Much of the land through which the projected line would run was derelict and could be acquired at a reasonable price. In a few years’ time it would be built upon and prohibitively expensive. Baron Lionel Rothschild reminded the meeting that land was changing hands in the City for as much as £1 million an acre. Pearson had earlier urged the Metropolitan Railway directors to ‘Tell the Corporation that if they do not come forward to help you, you will wind up the affair and that will be the end of it’.4 Following the meeting the deal was done.5 The Metropolitan Railway purchased the Fleet Valley land from the City for £179,157; in return the City Corporation subscribed £200,000 to the company’s capital. The Great Western subscribed £175,000. The remainder of the capital, some £475,000, was raised from civil engineers like Morton Peto and Thomas Brassey,6 who hoped to gain contracts, as well as from the Great Northern and Metropolitan Railway shareholders.

THE METROPOLITAN LINE

The Metropolitan Railway was the world’s first underground railway, though it firmly believed that it was really a main line railway, part of which, by painful necessity, happened to be built just below street level. Its steam service opened on 9 January 1863 running from Bishop’s Road station, near Paddington, to Farringdon Street in the City of London. Its tracks were dual gauge, accommodating both the standard gauge trains of the Metropolitan Railway itself and the broad gauge rolling stock of the Great Western running through from the main line at Paddington. In 1865 the line was extended to Moorgate Street and in 1868 further extensions were made, north to Swiss Cottage and south to Gloucester Road and South Kensington. From 1864 it also operated services via Westbourne Park and Shepherds Bush to Hammersmith, on what became the Hammersmith & City Line. After 1872 its new chairman, Sir Edward Watkin (see panel on p. 38), also chairman of the South Eastern Railway, embarked upon an ambitious programme of expansion and acquisition. In 1875 he extended the Metropolitan from Moorgate to Liverpool Street and in 1882 to Tower Hill. In 1878 he became chairman of the East London Railway (see panel on p. 36), from New Cross to Whitechapel, with an onward connection to Liverpool Street, to provide a link beneath the Thames to the South Eastern Railway. In the 1880s he extended the Metropolitan in a north-westerly direction to Harrow (1880), Pinner (1885) and Chesham (1889). Amersham and Aylesbury were reached in 1892, while in 1891 he had purchased the Aylesbury and Buckingham Railway, thus taking the ‘Metropolitan’ to the rural fastness of the Vale of Aylesbury. The original link to Paddington had become part of the Circle Line. Watkin’s plan, a century before its time, was to connect with main line railways to the north and take passengers from Manchester, via London, Dover and a Channel tunnel, to Paris. In 1899, after Watkin’s retirement, a further acquisition took the Metropolitan’s services to the village of Brill, 7 miles east of Aylesbury. Further extensions were built to Uxbridge (1904), Watford (1926) and Stanmore (1932), the last of these passing to the Bakerloo and then the Jubilee Line when it opened in 1979. In 1913 the Metropolitan had acquired the unloved Great Northern and City Tube (see p. 59) from Finsbury Park to Moorgate, which remained, however, unconnected to the rest of the company’s network. The Metropolitan electrified its services from 1905, though the section beyond Amersham remained steam-operated until it was transferred to British Rail in September 1961 following electrification of the stretch from Rickmansworth to Amersham and Chesham. The Metropolitan maintained its independence of the rest of the network until it was finally absorbed, protesting, by the London Passenger Transport Board in 1933.

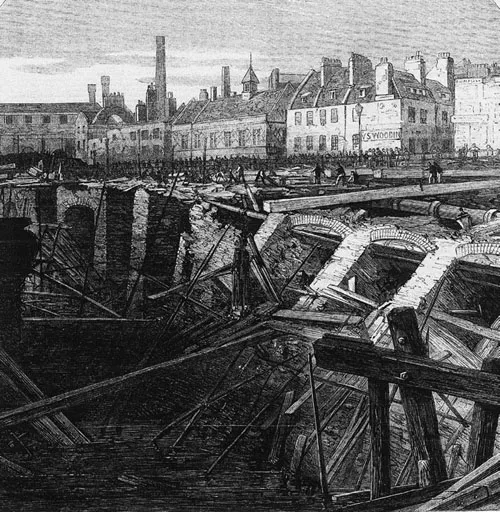

The River Fleet bursts in on the Metropolitan Railway construction works, a scene ‘well worthy of a visit’ according to the Illustrated London News.

The new company moved into offices at 17 Duke Street, Westminster, the former home of I.K. Brunel. In February 1860 work at last began on the railway, watched with a mixture of curiosity and disdain by the press and the public. One observer recorded: ‘A few wooden houses on wheels first made their appearance; then came some wagons loaded with timber and accompanied by sundry gravel-coloured men with picks and shovels.’7

The Times was more astringent, describing the scheme as ‘Utopian and one which, even if it could be accomplished, would certainly never pay’.8 The writer added, with unconscious foresight, that ‘the whole idea has been gradually associated with the plans for flying machines, warfare by balloons, tunnels under the Channel and other bold but hazardous propositions of the same kind’. The newspaper thought it ‘an insult to common sense to suppose that people would ever prefer to be driven amid palpable darkness through the foul subsoil of London’.

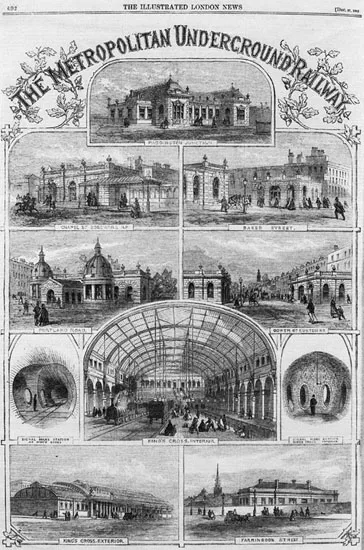

Stations on the New Metropolitan Railway as shown in the Illustrated London News on the opening of the line.

The line was built by the ‘cut and cover’ method. A trench was dug, mostly along the line of the Marylebone–Euston–Pentonville roads, with appalling effects upon traffic. Once the line was built, the trench was covered over and the traffic resumed its normal, congested course. Benjamin Baker, who had joined John Fowler in designing the system, described some of the problems encountered in constructing the world’s first underground railway at the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1885.9 Baker and Fowler later collaborated on their most celebrated railway project, the Forth Bridge. The construction of the railway was closely followed, especially by the Illustrated London News, which took many opportunities to publish engravings of the work in progress. On 15 February 1862, it published an illustration of the cutting as it passed ‘the summer residence of Nell Gwynne’.10 A more sombre note was sounded the following June when the Fleet sewer burst in upon the workings, and the newspaper marked the occasion with a scene of devastation on its front page and a vivid description of the event:

A warning was given by the cracking and heaving mass and the workmen had time to escape before the embankment fell in … the massive brick wall, eight feet six inches in thickness, thirty in height and a hundred yards long, rose bodily from its foundations as the water forced its way beneath … The scene was, indeed, well worthy of a visit.11

Several inspection visits were carried out before the line officially opened, some of them arranged for publicity purposes. There exists a photograph of Gladstone on one of these occasions, looking distinctly out of place in an open goods wagon at Edgware Road in May 1862, shortly before the Fleet burst. On another such inspection visit, reported in the Illustrated London News on 6 September 1862,12 the newspaper’s correspondent described the curious sensation of agreeable disappointment – the open cuttings being more extensive, and the tunnels better lighted and ventilated, than was expected.

‘THE GREAT ENGINEERING TRIUMPH OF THE DAY’

On 9 January 1863 the line was formally opened by the directors. Shortly before the opening they had referred to arbitration a late request for extra payments in connection with the opening by their engineer John Fowler, who was gaining a reputation for being distinctly acquisitive.13 The previous week the Illustrated London News had announced the event and devoted a full page to illustrations of each of the seven stations served by the new route. A ceremonial tour of the new line was undertaken by the directors and about 700 guests. Sir Rowland Hill was among the guests but the prime minister, Lord Palmerston, was not. He had been invited but the 79-year-old statesman had declined, saying that he hoped to remain above ground a little while longer. He died two years later. Another absentee was Charles Pearson; he had lived to see his idea taking shape but had died the previous September before it was completed. A banquet was held at the Farringdon Street terminus at which an atmosphere of mutual congratulation prevailed. The Metropolitan Police band played, speeches were made and toasts drunk to the manifold virtues of the City Corporation, the civil engineering profession in general and to John Fowler in particular. The Times, whose earlier scepticism was forgotten amid the enthusiasm of the occasion, declared:

The Metropolitan Railway has at length become ‘a great fact’ and, we may add, a great success … the line may be regarded as the great engineering triumph of the day … ingenious contrivances for obtaining light and ventilation were particularly commended.14

The ‘ingenious contrivances’ consisted of lengths of cutting open to the sky (still a characteristic of much of the Metropolitan and Circle Line, for example at Farringdon) and coal gas lamps in huge globes hanging from the station roofs. Robert Lowe MP, Gladstone’s future Chancellor of the Exchequer, made the principal speech, in which he expressed his confidence that the new line would form the basis of a ‘Circle’ of such railways within the metropolis. This would follow, but not until another twenty-one years had passed.

In his...