![]()

11

‘Les Poilus’ postcard

Country of origin: France

Date of printing: 1914

Location: Private collection

EACH COUNTRY HAD its image of military perfection and its name for the military defender of the nation. For the German soldier (soldat), it was the transformation from simple soldier to trained Landser that was revered, and only those men experienced enough in war could hope to attain this status amongst their comrades (kamaraden). Slang versions used by the soldiers themselves included the obvious landratte (land rat). The reverence for the soldier in Germany contrasts somewhat with the approach adopted by the Entente countries, particularly Britain and France. Here, the popular imagination did not frame soldiers as upright individuals fully equipped with rifle and bayonet, and ready to take on the foe; instead they were portrayed as more individual, perhaps in keeping with perceived national characteristics.

For the British, the name most commonly applied was ‘Tommy’, or ‘Tommy Atkins’. This mostly affectionate term appeared originally in the early part of the nineteenth century, applied as shorthand for the British soldier in official correspondence, but by the late nineteenth century, it was widely used in the popular press, made famous in part by the writings of Rudyard Kipling. Tommy Atkins appeared in songs, in the press and on postcards. Although there were some dissenting voices from the ranks, the name stuck. Amongst other English-speaking soldiers, ‘diggers’ was applied to Australians and ‘doughboys’ applied to Americans. The origins of both of these are obscure. ‘Digger’ possibly derives from advice given by General Sir Ian Hamilton to the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC) during the Gallipoli landings in 1915 – that they should dig in in order to consolidate their positions – but others argue it relates to nineteenth-century Australian gold mining. ‘Doughboy’ is even more ambiguous, possibly stemming from the dusty uniforms worn by American soldiers in the mid-nineteenth-century Mexican-American War. In any case, all the terms were applied in an effort to give familiar names to the average soldier.

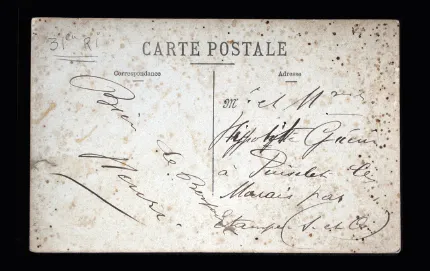

The rear of the card, expressing good wishes.

The object in this case is a photograph – one of many hundreds of thousands (if not millions) that were produced of soldiers during the war. With photography well established, it was commonplace that families visited photographic studios in order to gain a likeness they could pass on to family members. Usually set in formal poses, families stare at the camera or beyond it, careful not to move so that slow shutter speeds could capture their poses without blurring. With the coming of war, photographers were called upon to supply images of soldiers in uniform, an opportunity to record that men or women were ‘doing their bit’ for their country. Common to all nations, studios did brisk business in supplying these needs, and in the battle zone, enterprising photographers were on hand to capture the likeness of men in uniform, to be sent home with a brief comment: ‘I am well, hope you are too.’ The sadness is that in many cases the soldiers depicted were killed before they could return to pick up their orders.

The photograph shows three men of the French 31st Infantry Regiment at a camp in 1914. Relaxed in pose, the men are equipped with pantalon garance, red-topped kepis and dark blue capote (the typical greatcoat of the French soldier, buttoned back to allow for marching), together with the standard black leather pattern 1888 equipment and Lebel rifles. The photograph gives few clues about the men’s names or, ultimately, their fates. The term poilu (meaning ‘hairy’ or ‘shaggy’) was used widely for the French soldier, both amongst the French and occasionally by his British and, later, American allies. The three men in the photograph are typical, if perhaps more groomed than would be seen commonly in the trenches, with flamboyant moustaches and goatee beards. With France mostly an agricultural country, the adoption of the name poilu might have resonated with the wider agrarian population of the country. Yet the name is supposed to have originated in a story by Honoré de Balzac, Le Médecin de Campagne (1834), in which a group of French soldiers are required for a deed demanding particular courage. Only forty soldiers in one regiment are deemed to be assez poilu (‘hairy enough’). Poilu was also commonly familiarised as piou-piou.

Piou-Piou

The British Tommy Atkins to the French

YOUR trousies is a funny red,

Your tunic is a funny blue,

Your cap sets curious on your ’ead–

And yet, by Gawd, your ’eart sits true, Piou-piou!

Second Lieutenant Joseph Lee, KRRC Ballads of Battle, 1919

12

Russian furazhka

Country of origin: Russia

Date of manufacture: c. 1914–17

Location: In Flanders Fields Museum, Ieper, Belgium

THE ARMIES OF 1914 were distinguished from one another in form of dress, equipment and munitions. Typical of all Allied nations was the use of some form of soft cap, the style of which was influenced by national characteristics. These caps contrasted heavily with the imperial German spiked helmet, the Helm mit Spitze or Pickelhaube, which provided little in the way of protection and was parodied mercilessly in propaganda to send up the ‘German hordes’. In 1914, Belgian and French infantrymen wore similarly archaic headgear: the Belgian shako, complete with pompom, that, in design terms, harked back at least a century, and the French kepi, practical in design yet dramatic in colour, with red top and dark blue band, first introduced in 1884. The British and Russians, in contrast, wore simple khaki-coloured peaked caps that had been born out of their experiences in the earliest wars of the twentieth century, in South Africa and the Russo-Japanese War.

The defeats suffered in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904–05 took a heavy toll on the Russians; no longer could they afford to go to war with outdated equipment and tactics. The Russian uniform was distinctive: a long pullover tunic shirt with stand-up collar known as the гимнастёрка (gymnasterka). Without direct equivalents (other than the tunic worn by the British Indian Army), this item, first introduced in 1870, drew on peasant traditions to become one of the most distinctive items of the Russian Army. But in its original form – as a distinctly white uniform – it was vulnerable, and it was replaced by a khaki version in the prelude to war. Accompanying this was a peaked cap known as the Фуражка (furazhka), which was introduced in 1907. Both items were theoretically issued in cotton for the hot continental summers and wool for winter – though this would be replaced in the depths of winter by a fleece known as папáха (papakha). Our example is a rare survivor of the furazhka.

Russian frontovik prisoners of war in Germany, wearing the furazhka.

It is simple in design, similar in many ways to the British Service dress cap – introduced in 1905 – though it was less formal and was easily moulded to fit the wearer’s head comfortably. The British cap was stiff, and it was only the rigours of the front-line trenches that transformed it into something more malleable that could be modified and shaped. Our cap retains something of its original shape and probably did not see much service in the front line, worn by a veteran soldier (frontovik). Lacking a chinstrap, and with a distinctive short leather peak, the cap was there to demand uniformity of dress and to act as a platform for the distinctive regimental insignia – the imperial cockade. For ordinary soldiers, the cockade was nothing more than a simple pressed-metal disc that was painted in the Russian imperial colours of orange and black; for officers, it was more ornate, better made and distinctly raised in style. Our cap is an ordinary infantryman’s.

The transformation from cap to steel helmet in most armies in 1915–16 marks the transition from open warfare to the entrenched positions that were ultimately to blight the landscape of Europe and, in the west at least, turned the war into the longest extended siege in history. In Greater Russia, trench warfare was less sustainable, and troops moving in open fields were still a distinctive feature of the war there. Without long trench lines, positions were more easily outflanked, but the attackers were more often than not dangerously exposed, with limited opportunity to supply and reinforce. With trenches so prevalent in the west and with head wounds consequently so common – as soldiers were tempted to put their heads above the parapet or tall soldiers forgot to duck – steel helmets had become the norm by the close of 1915. In the east, the helmet took longer to appear, the cap lingering on as supply issues began to bite, an echo of the open warfare that persisted in the wide, rolling landscapes of the Eastern Front.

13

Canadian insignia

Country of origin: Canada

Date of manufacture: 1914–18

Location: Private collection

REGIMENTAL DEVICES ARE of the greatest importance in warfare. In a military sense, distinguishing friend from foe on the battlefield has long been an important expedient, and the use of some identifying device in the years before uniforms was essential. Though temporary ‘field signs’ (i.e. branches, foliage, paper scraps) had been used since at least the Middle Ages, perhaps the earliest metal military uniform badges were one-sided silver badges sewn directly to the clothing by Royalist soldiers during the English Civil War – but it would be some time before real ‘cap badges’ would be worn. In the British Army, the wearing of metal headdress badges followed the introduction, in 1800, of the shako – an unwieldy piece of headgear that was finally abolished in 1878.

In the British and Imperial Armies, with the arrival of khaki service dress in the early twentieth century came the adoption of a cap. New badges were called for, and from 1898, new designs were in place that would come to personify the regiment, widely used and reproduced in a number of settings, both domestic and military. This practice differs from most other nations at the time. For France, Italy, Belgium or Germany, for example, infantry battalions were simply identified through the use of numerals most often displayed on shoulder straps or collars – though branches of service, such as the artillery, were commonly identified by the tools of their trade (i.e. crossed cannons).

Pragmatically, the use of regimental insignia on caps and other headdress was intended to identify the unit to the casual observer, but there is more to it than that. Propagation of the ‘love of one’s regiment’ was a very real principle in cementing the solid rela...