- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

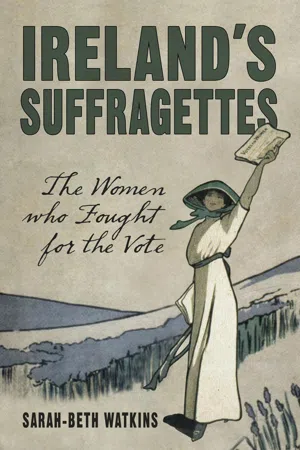

About this book

Ireland's Suffragettes is a collection of biographical essays introducing the suffragettes who influenced Ireland's struggle for women's rights. Many of the women were political activists while others became militant suffragettes between 1912 and 1914. The struggle of the suffragettes is different to that of the UK, in that many Irish suffragettes were also included in the struggle for independence and the inclusion of women in the trade unions movement. Drawing on primary sources located in the National Archives and the National Library, Ireland's Suffragettes will bring to life not only the most famous names in the suffragette movement but also the other women who made women's rights their lives work.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ireland's Suffragettes by Sarah-Beth Watkins in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Sozialwissenschaften & Sozialwissenschaftliche Biographien. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Political Suffragettes

Anna Haslam

(1829–1922)

Anna Haslam was born in 1829 to a Quaker family living in Youghal, County Cork. Born Anna Maria Fisher, she married Thomas Haslam in 1854 who was also from a Quaker family residing in Mountmellick, County Laois and they moved to Dublin in 1858. Anna spent her early life teaching knitting and lacemaking to young girls and she established her own lacemaking business that she then passed on to the Presentation nuns. She attended a talk in Blackrock by Anne Robertson, a feminist speaker, around 1858 and was inspired her to join the suffrage movement and organise further meetings for feminist speakers to spread the message of women’s empowerment and advocate for the right to vote.

In 1866, the first petition seeking suffrage for women was presented to the House of Commons by John Stuart Mill. Twenty-five Irish women had added their signatures, including Anna. Mill corresponded with Thomas, Anna’s husband, over the possibility of setting up an Irish suffrage society in Dublin but Mill felt that the immediate prospects were not encouraging. Although his comments may have delayed the setting up of such a society, Anna and Thomas were not to be deterred.

In the February of 1876, Anna, along with her husband, founded the first Irish suffrage society in Dublin, the DWSA. Its members were mostly Quakers and by 1896, it only had a membership of forty-three but this gradually rose to 647 by 1911. Anna was to spend many years as its secretary, stepping down in 1913 but remaining its life president. Throughout her years as secretary Anna kept diligent records and minutes of meetings that set out the work of the organisation and all its involvement in various campaigns.

The DWSA was a non-militant organisation that aimed to raise public awareness of the suffrage movement and began by engaging women (and men) in discussion at drawing room meetings. These were mostly conducted in the Haslam’s home on the Rathmines Road. The association kept a close eye on political developments at home and in the UK and encouraged women to contact their MPs to bring their attention to bills and amendments that would affect women and to seek their support in lobbying for change. Whenever there was debate regarding women’s suffrage in the House of Commons, the society called on Irish MPs, influential people and the press to rally to their cause. Thomas also edited a published journal in 1874, The Women’s Advocate. It only ran to three issues but outlined the DWSA’s actions and policies. It was so popular, however, with the English suffragette Lydia Becker that 5,000 copies were printed for dissemination.

The DWSA began sending delegates to feminist conferences and speeches where they met with other women from Ireland and the UK who were mobilising for the right to vote as well as other campaigns, including educational reform and the right for a married woman to control her own property. Anna and her husband regularly travelled to attend other suffrage meetings, conferences and demonstrations. In October of 1896, Anna travelled to Birmingham to attend a national conference. It was here that the idea of joining forces to build a National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) was discussed and both the DWSA and its Belfast equivalent became founding members.

In 1898 the Local Government Act became a focus of Anne’s attentions; it allowed for county councils and urban and rural district councils to be elected and for women with certain property qualifications to be eligible to sit on these new bodies. It became such an important part of the struggle for women’s rights that the DWSA changed its name to the IWSLGA. Women were encouraged to become more and more involved in politics on a local level as well as nationally.

Anna travelled to the UK again in 1903 as part of a delegation to attend the Conference of the National Convention in Defence of the Civil Rights of Women. In Holborn Town Hall, plans were made to hold mass general meetings across the UK and Ireland. Returning home, Anna helped to organise the Dublin meeting at the Mansion House on 14 January 1904.

Many of the women featured in this book began their suffrage involvement through the IWSLGA. Younger women wanted to take more militant action but Anna and Thomas Haslam always remained pacifist in their views and their running of the organisation. In 1908, Hanna Sheehy Skeffington, Margaret Cousins and other interested women were discussing the formation of a more militant society, the IWFL. In Margaret’s autobiography, she recalls, ‘So a group of us went on November 6 to the dear old leader of the constitutional suffragettes, Mrs Anna Haslam, to inform her that we younger women were ready to start a new women’s suffrage society on militant lines. She regretted what she felt to be a duplication of effort.’

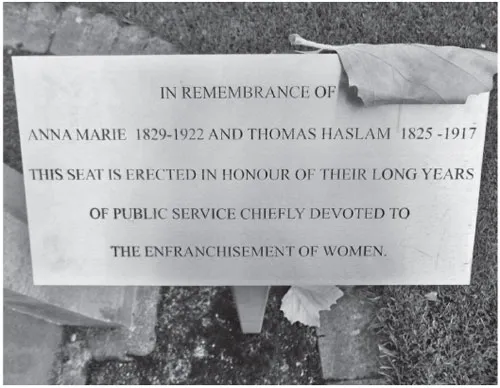

Transcript of dedication to Anna and Thomas Haslam. (© J.R. Webb)

The Haslams’ memorial seat at St Stephen’s Green. (© J.R. Webb)

She may have seemed like an older woman, set in her pacifist ways to the younger generations of suffragettes, but she had established the suffrage movement in Ireland and begun a process that would result in the culmination of all their hopes. Thomas died in 1917 before the General Election of 1918 where women over 30 were allowed to vote for the first time. Anna, however, after years of suffrage involvement, took the opportunity to cast her vote, something that she had worked for all her life. On that day she was presented with a bouquet of flowers in the suffragette colours and was congratulated by many of the women who had followed in her footsteps.

Anna died in 1922, the same year women in Ireland over 21 could vote for parliament on the same basis as men. On St Stephen’s Green, there is a stone seat dedicated to the memory of both Anna and Thomas and their commitment to Ireland’s suffrage movement and the achievement of the vote for women.

Louie Bennett

(1870–1956)

Born in 1870, Louie had a middle-class background. She attended boarding school in the UK, Alexandra College in Dublin and went on to study music in Bonn, Germany. How she came to be involved in the suffragette movement is unknown but from the late 1800s suffragette societies were emerging in Ireland in response to changing social and political times.

Louie Bennett was involved in the establishment of three organisations: the IWSF, the Irish Women’s Reform League (IWRL) and the IWWU. The year 1911 marked Louie Bennett’s emergence into the public arena as she became one of Ireland’s foremost suffragettes, a trade unionist and peace advocate.

In 1911, the year when women refused to participate in the census in protest of their lack of a vote, Louie joined with Helen Chenevix to establish the IWSF. This absorbed the IWSLGA and local suffrage groups from around the country. By 1913, fifteen groups had joined the organisation including Derry, Lisburn, Belfast, Galway, Waterford and Birr. Contrary to other suffragette organisations, it was non-party political and non-militant, although Louie stated that she would not condemn any woman acting militantly. She saw the aim of the organisation as one of propaganda and education. By working together and women having the vote, it would be beneficial for the welfare of Ireland.

In 1913, she was one of only three Irish women who attended the International Women’s Suffrage Alliance in Budapest. The International Alliance was founded by American suffragettes on the principle that women should have equal rights and equal responsibilities. 1913 was also the year of the Dublin Lockout and Louie became more involved in the plight of women and work. She was involved in a scheme with the lady mayoress to aid striker’s families and could be found working in the soup kitchens alongside Countess de Markievicz, Hannah Sheehy Skeffington and Delia Larkin.

The IWRL became an important part of her work for women. It campaigned to provide school meals and advocated the technical education of girls. A committee was set up to watch legislation that affected women and the courts were monitored for cases of injustice to women and younger girls. An investigation into women workers in Dublin factories found that they were paid much less than their male counterparts.

Louie’s work effectively linked the labour and suffrage movements. However, Louie was reticent in becoming involved in trade unions because she had reservations about Connolly’s policy of combining nationalist and labour activities, as most Irish Nationalist MPs were opposed to giving women the vote. In 1916, she changed her mind and became more involved in trade union affairs. She took over leadership of the IWWU and became editor of the Irish Citizen, the suffrage newspaper. In 1917, she became the organisations secretary and stayed in the position until 1955. The IWWU were instrumental in seeking change in women’s working conditions, pay and holiday entitlements.

In January 1918, Louie wrote in the Irish Citizen:

The most notable development of the women’s movement in Ireland during the past year has been the sudden growth of trade unionism amongst women workers. A year ago the members of the Irish Women Workers Union numbered only a few hundreds: now they are over 2,000. The Munition workers are strongly organised under the national Federation of Women Workers; tailoresses, shirt-makers and other workers with the needle are enrolling in great numbers in all the big towns in the Society of Tailors and Tailoresses. Women clerks are now amongst the keenest and most active members of the Irish Clerical Union and the National Union of Clerks, although this time last year the women clerks of Dublin were still in doubt whether they were not too nice for anything resembling a Union! The most interesting point in regard to this rapid organisation is the spirit in which the women have come into the movement; this spirit promises to atone for their tardiness in entering. They are keen and progressive; quick in their grasp of the fundamental principles of trade unionism, and loyal in adherence to them. The stand the women in the printing trade made during the recent printers’ strike was a surprise to many people – not least, perhaps the employers!

Do the women of other classes realise how significant and how far-reaching in effect this development amongst Irish women workers will prove? Hitherto, these women have spent their idealism and loyalty mainly on nationalism. Now their nationalism promises to express itself in a practical direction, and women will find the best means of serving Ireland through the power of the trade union. When they have lifted themselves out of the sweated conditions under which they work at present, we shall begin to feel their influence in broader directions and stimulating the civic reforms which all classes’ desire but which only workers themselves will ever effectually achieve.’1

Members of the Irish Women Workers’ Union. (© National Library of Ireland)

The IWWU also campaigned against conscription in 1918. This was to be a momentous year as the Representation of People Act granted the vote for women over 30 years of age. The Labour Party, impressed by Louie’s work, nominated her as a candidate for the general election of 1918. She was their first female candidate. However, Louie declined the invitation.

Louie’s interests varied, including travel, politics and more. She attended the 1919 International Congress of Women in Zurich and in 1920 she went to America to raise support against Britain’s use of the Black and Tans in Ireland. She was an executive member of the Irish Trade Union Congress 1927–1931 and 1944–1950. She became their first female president in 1932 and again in 1948.

The memorial seat of Louie Bennett and Helen Chenevix. (© J.R. Webb)

At the IWWU annual convention in 1935, Louie demanded equal status for all workers and a pay scale to reflect wages based on work and not sex discrimination. At this time single women were being paid the lowest wage, single men the middle income and married men the highest. Of course, married women weren’t allowed to work at all.

Ten years later, she was still working for female workers’ rights when she supported the 1945 laundry strike in aid of a fortnight’s paid holiday; 1,500 laundry workers went on strike for fourteen weeks. They worked in conditions that led to tuberculosis and rheumatism, without a break or holiday, and Louie supported their cause through to its successful conclusion. Housing was also an issue for Louie and she campaigned tirelessly for slum clearance and the development of proper housing for the low paid. As she grew older, she also became interested in the need for nuclear disarmament and the banning of nuclear power.

Louie died in her eighty-seventh year, after a lifetime of working for women, whether it was seeking the vote or looking for reform and making women’s work conditions better. She had not married or had children, but devoted her life for the good of others. She campaigned and protested throughout her life and fought for causes that we take for granted nowadays.

Charlotte Despard

(1844–1939)

Charlotte was born in Ripple, Kent to Commander John Tracy William French and Margaret (née Eccles). Her father was from Frenchpark, County Roscommon and was a naval officer. At the age of 10, after her father died and her mother was committed to an asylum, Charlotte was sent to live with relations in London.

In 1870, Charlotte married Maximilian Carden Despard, an Anglo-Irish businessman who had made a fortune in the Far East by cofounding the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank. He encouraged her love of writing in their early years of marriage and as they travelled abroad, she wrote ten novels and many poems. She was to continue to write poetry, stories and suffrage propaganda throughout her life. After her husband died in 1890, Charlotte suffered a breakdown and when she emerged it was to begin her political life and fight for women’s rights. She became involved in charity and poor relief work in Nine Elms, an Irish populated slum district of London and was elected to be a Poor Law Guardian for Lambeth. Her work in Nine Elms included setting up working men’s clubs, youth clubs, a health clinic and a soup kitchen. It was at this time that she converted to Catholicism.

Charlotte’s life was a tale of two countries; she would be involved in politics and the suffrage movement on both sides of the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- The Militant Suffragettes

- The English Suffragettes

- The Belfast Suffragettes

- The Political Suffragettes

- Afterword

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Copyright