![]()

1

THE NEW SCRAMBLE, GEOGRAPHY AND DEVELOPMENT

State weakness invites external exploitation and much of Africa represents a power vacuum that predatory outsiders are only too anxious to fill as they search for resources in an ever more competitive world. (Arnold 2009, p. 9)

As the global economy continues to grow, while natural resources remain fixed, there is an imperative for industrial and industrializing countries to open up new long-term sources of raw material supply. The rise of China is particularly significant in this regard, given its voracious demand, as are the other so-called ‘Asian Driver’ economies such as India and other regional middle powers such as Brazil. China’s economic growth over the last thirty years has been phenomenal, averaging 10 per cent a year. This gives a doubling time of seven years and the move from it being an oil exporter to an oil importer in the mid-1990s gave rise to the need for China to source this commodity around the world.

As noted earlier, there are substantial differences between the first scramble for Africa in the nineteenth century and the current one. According to Satgar (2009, p. 37) ‘the nature of rivalry today is not inter-imperialist but global. This is observable on the African continent in various sectors as transnational capital scrambles to capture resources to meet the needs of global capitalism.’ However, transnational corporations’ (TNCs’) home country governments also play an increasingly important role in support of ‘their’ companies, and major powers have interests in Africa outside of direct economic ones as well, particularly in relation to security.

Talk of the ‘new scramble for Africa’ may serve to reinforce images of Africans as passive and powerless, which are now very far from accurate, particularly as regards government leaders who are finding their power strengthened (Perrot and Malaquais 2009). African governments now act as gatekeepers for resources and often hold shares in companies undertaking their exploitation. Consequently, access to resources is now based on bargaining relationships, rather than the brute force that characterized the colonial period. This is leading to novel reconfigurations of politics, power and the economic geography of the continent, although there are still similarities with the first scramble.

According to Okeke (2008, p. 194), ‘just like the first scramble, the second scramble is clearly more beneficial to the main actors – that is, the private foreign corporations and their home governments – than to African governments and people’. However, as will be discussed below, the rewards for African elites can be very substantial, even if the proportionate rewards to international corporations are bigger in certain cases. Thus the current relations must be characterized as post-imperial ones, in which national elites have substantial power in their bargaining with external actors (Becker and Sklar 1999). The extent to which this new configuration will lead to substantial poverty reduction on the continent, however, remains an open question

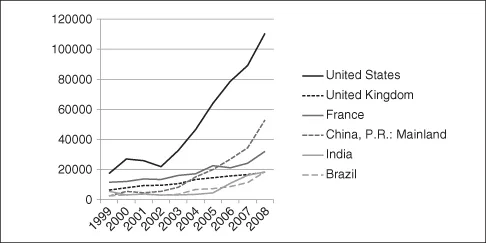

The paradox of plenty, or ‘resource curse’ – that Africa is mineral-rich, but the poorest and most conflicted continent in the world – was noted earlier. Africa has about 30 per cent of the world’s mineral reserves, including 90 per cent of the world’s platinum and 40 per cent of its gold (Southall 2009). However, these resources have typically only benefited elites in Africa in partnership with foreign interests and external powers. Resource scarcity is leading to deepening levels of investment and interconnection of Africa with the global economy: a new period of evolution in the globalization of the continent. The scale of increased economic interconnection or globalization between Africa and elsewhere can be demonstrated by a simple graph of exports from Africa to some of the world’s major economic powers (figure 1.1). The vast majority of increased exports to the United States are of oil. What does the increasing globalization of the continent mean for its peoples?

Globalization is often defined as increased interconnectedness between places. The creation of a global economy characterized by ‘network trade’ – whereby components from around the world go into final products – ‘deep integration’ – whereby different countries harmonize their laws and regulations in relation to trade and investment – and increased information exchange is often presented in mainstream accounts as a benign phenomenon which enables the ‘connection of the disconnected’ in the developing world. However, social and economic networks are not ‘flat’ but structured by hierarchy as the actors involved have different types and levels of power. Consequently, both growth and uneven development continue to shape the evolution of the global economy and of Africa. The new scramble for Africa represents a deepening of the process of globalization on the continent, which is reshaping its geography. Recently, however, the process of economic globalization has undergone a setback.

According to the IMF, the global economy contracted by 0.8 per cent in 2009. Nonetheless, that year the Economist Intelligence Unit had predicted that SSA would be home to seven of the top ten fastest-growing economies in the world, as oil importers such as Malawi benefited from favourable movements in the terms of trade as the price of oil fell. As it turned out, these predictions were not generally realized, although Malawi was one of the world’s top fifteen fastest-growing economies in the world that year.

As a whole SSA had an economic growth rate of 5.6 per cent in 2008. This fell to 1.6 per cent in 2009, and the IMF predicted growth for the sub-continent of 4.3 per cent in 2010. However, economic growth is likely to return to high levels in the medium to long term as global resource scarcity becomes more acute. However, the nature and quality of this growth is important. As this book will show, it is based primarily on investment and trade in raw materials and mineral exploitation and exports, and as a result risks reinscribing Africa’s previous unfavourable relations with the international system.

More than half of the population of SSA live on less than the equivalent of what a dollar a day would buy in the United States. Recently there has been a substantial debate about the causes of African underdevelopment, with some ascribing it to Africa’s ‘natural geographic disadvantages’. However, the deepening of the process of globalization on the continent is reconfiguring its socio-economic geography and linking it more closely to other places. In order to understand the nature of African underdevelopment and how it is being reconfigured by globalization, it is worthwhile examining the relationship between geography and development.

Geography and Development in Africa

In the last 25 years, we find that the bottom half of world income earners seems to have gained something in relation to the top half … but the bottom 10 per cent have lost seriously in comparison to the top 10 per cent. (Sutcliffe 2007, p. 71)

At the root of Africa’s impoverishment, in our view, lies its extraordinarily disadvantageous geography, which has helped to shape the nature of African societies and Africa’s interactions with the rest of the world. (Bloom and Sachs 1998, p. 4)

The most well-known recent explanations for Africa’s underdevelopment are linked to its physical geography. For some, Africa is a victim of its geography, with many landlocked countries, far from world markets and with a particularly dangerous type of mosquito. For the well-known Oxford economist Paul Collier, and Jeffrey Sachs in his earlier work, internal geography or site characteristics are most important. Africa is ‘cursed’ by its resources, and by many countries having ‘bad neighbours’. According to Jeffrey Sachs (2008, p. 50), ‘The challenge now is that extreme poverty is concentrated in the toughest places: landlocked, tropical, drought-prone, malaria-ridden, and off the world’s main trade routes. It is no accident that today’s poorest places have been the last to catch the wave of globalisation. They have the most difficulty in getting on the ladder of development.’

In this reading, Africa is by-passed by globalization because: ‘when the preconditions of basic infrastructure (roads, power and ports) and human capital (health and education) are in place, markets are powerful engines of development. Without these preconditions, markets can cruelly bypass large parts of the world, leaving them impoverished and suffering without respite’ (Sachs 2005, p. 3). For Jeffrey Sachs the free market of a ‘laissez faire’ (literally ‘let do’) approach to African development is a ‘murderous’ one and there needs to be massive public investment so that Africa can take advantage of the opportunities of globalization (Sachs 2010). The levelling effects of the global free market are countered by ‘natural’ geographic disadvantages which can be overcome by infrastructural and other public goods investments, some of which may now be provided by China in particular.

For Paul Collier (2009), Africa is cursed by its resources and many countries are situated in ‘bad neighbourhoods’. These themes have also been taken up in the recent 2009 World Development Report, Reshaping Economic Geography. A central theme of this report is that there is a need to integrate Africa more fully into the global economy through a reduction of ‘distance’ from world markets.

What these influential accounts share is an emphasis on what geographers call first nature geography – or the natural geography of coastlines, mountains and physical distance (Sheppard 2011). While not denying that landlocked states may face particular challenges, these accounts neglect the way in which ‘distance’ from world markets has been created. Why is Chicago central while Kigali, the capital of Rwanda, is peripheral to global flows of investment and trade? Only by taking a historical approach which examines the interactions between the past and the present can we understand the ongoing construction of African underdevelopment (Cox 1987).

Some recent mainstream approaches to African development have been critiqued as environmentally deterministic and lacking historical perspective. While more recent work by some mainstream economists now analyses the social construction and political economy of the resource curse, ‘bad neighbourhoods’ and the environment (Humphreys, Sachs and Stiglitz 2007), this is where mainstream work is generally weakest.

Geography, particularly socio-economic geography, is largely socially constructed, rather than being a natural artefact. While it may be uneconomic to grow bananas in Britain, it does not follow that steel should not be made in Senegal or Singapore. Resource dependency and lack of value addition in Africa are central to the continent’s underdevelopment.

In the economics literature there has been a substantial debate about whether it is institutions or geography which most determine (Africa’s) economic development. However, this misses an important point – institutions are geography. According to noted political theorist Raymond Duvall, institutions are structured sets of practices informed by shared sets of meanings and understandings. These practices occur in particular places and hence create socio-economic geographies. Consequently, rather than the resource curse being a ‘natural’ condition, it can be conceptualized as a mode of governance which involves coordination between domestic and transnational elites to secure access to resource revenues or rents. Because of the inequality and exclusion associated with this bargain, instability and conflict arise in Africa and elsewhere.

While the developed world, in general, experienced continued economic growth from 1980 to 2000, average incomes in SSA, despite its rich resources, declined by about 15 per cent (Weisbrot, Baker and Rosnick 2007). The manifest failure of Africa to develop economically despite the implementation of market-led reforms across the continent has led to a new focus in mainstream work on the ‘new’ economic geography to explain the continent’s underdevelopment. This ‘new economic geography’ often uses sophisticated mathematical models, but its core ideas can be easily explained, and, while they seem intuitive, they are misleading.

Paul Krugman won a Nobel prize in 2008 for his work on how economies of scale, whereby bigger factories are more efficient, can lead to uneven development (Krugman 1991), a fact long known to economic geographers, whereas Jared Diamond, a biologist, in his work has argued that initial environmental conditions explain developmental divergence across continents (Diamond 1997). These two strands of work have recently been brought together by other economists and development institutions to explain Africa’s general developmental failure. However, this chapter argues that current explanations for African underdevelopment by some economists and the World Bank have a number of critical flaws, as they are largely ahistorical and neglect the global politics of power and inequality. Through an examination of these issues, the nature of uneven development and African underdevelopment can be illuminated.

The Inequality of Geography or the Geography of Inequality?

There is no agreed-upon definition of what constitutes geography as a discipline, or perspective. For non-geographers the term is often synonymous with physical geography – the ways in which physical features are shaped and located and the impacts that these have on human settlements and patterns of economic activity. However, for geographers what is more important in determining developmental patterns is the way in which the relationships between places – or social agents embedded in them – are constructed. This is not to discount the importance of agro-ecological conditions, for example, but acknowledges these are, partially, human artefacts.

In the post-independence period, more autonomous economic strategies were tried in Africa. Western allies such as Mobutu in Zaire effectively nationalized much of the formal sector of the economy, and the West, through the World Bank for example, was willing to support Tanzania’s – ultimately failed – strategy of socialist transformation, as long as the country remained politically non-aligned. Development strategies of the time were heavily influenced by ideas about ‘delinking’ from an exploitative global economy. However, with the end of the Cold War, such experiments were no longer tolerated. In future the market, and the market alone, would determine the prices for Africa’s exports, unless of course these were also influenced by European and American subsidies for their own agricultural products, such as cotton and sugar.

During the 1980s and 1990s much of the Third World undertook programmes of economic restructuring sponsored by the World Bank and the IMF, both of which are headquartered in Washington, DC, and controlled by their largest stake- or share-holders, the rich industrial countries – particularly the United States, which is the only country to hold veto power in both institutions.

These ‘structural adjustment programmes’ (SAPs) promoted by the World Bank and IMF centred on liberalization, privatization and state cut-backs or retrenchment. African countries which undertook them generally eliminated so-called ‘quantitative restrictions’ on imports, drastically reduced import tariffs, opened their economies to foreign investment and privatized many state-owned industries. Indeed it was these SAPs which set the stage for the new scramble for Africa by opening up what had often been relatively closed economies (Kragelund 2009). SAPs were meant to (re)integrate Africa into the global economy.

Structural adjustment was notably unsuccessful in achieving its ostensible objectives of economic diversification (Bloom and Sachs 1998) and poverty alleviation (Cheru 2002) however. It turned out that simply ‘getting the policies right’ would not deliver improvements in living standards, although there was also substantial debate about the extent to which these policies were faithfully implemented by often corrupt political elites in Africa (Van de Walle 2001).

The widely acknowledged failure of programmes of economic liberalization in Africa generated a host of different explanations, ranging from the supposedly unique political structures of African societies to a lack of social capital or social ties between individuals and communities (Carmody 2007). As noted above, however, recently the general failure of economic development in Africa has been presented as a result of its geography, and how this interacts with the continent’s politics. In some of these readings ‘natural’ geographic disadvantages have isolated Africa from the positive effects of economic globalization, while its primordialist identities have corrupted its politics in an interacting vicious circle.

The recent annual World Development Report of the World Bank (2009), which is the world’s leading development institution and think tank, pays particular attention to geography, especially ideas about first and second nature geography. While first nature geography refers to physical geography, ‘second nature emphasizes the gains from proximity’ as firms cluster (Kanbur and Venables 2007, p. 204). Clustering reduces transaction costs between related and supporting firms. It allows pools of skilled labour to develop, and knowledge on best practices to be transferred between firms. In its report, however, the World Bank also emphasizes that Africa was affected by the colonial experience, particularly the Congress of Berlin.

According to the World Development Report (2009, p. 283), ‘For Sub-Saharan Africa, the Berlin conference was just the last in a long line of what geographers have termed “formative disasters”, unfavorably altering the human, physical, and political geography of the continent, creating continentwide problems of low density, long distances, and divided countries.’ However, while there were extensive ecological transformations, such as the development of plantations, associated with colonialism, the physical geography of the continent was not substantially altered. Perhaps more interesting is the admission that colonialism is responsible for ‘low density’ in Africa.

In the World Bank definition, ‘density refers to the economic mass per unit of land area, or the geographic compactness of economic activity. It is shorthand for the level of output produced – and thus the income generated – per unit of land area’ (p. 49). How did the legacy of colonialism affect post-colonial development?

The World Bank’s report suggests, in places, that it is the colonial division of Africa which is at the root of the continent’s current problems, a proposition around which there is substantial agreement. However, in other parts of the same report it is argued that it is ‘first-nature geography’ or the physical characteristics of a place which largely determines its developmental potential in the first instance, as this kick-starts a process of cumulative causation – or a kind of snowball effect – leading to developmental divergence. This idea of cumulative climatic causation is similar to ideas in the new geographical economics about economies of scale (Krugman 1991). This idea is itself economical; it doesn’t deal with the messiness of politics, for example, and can potentially be seen as an attempt to constitute a new ‘common sense’ or hegemony – ‘Africa is poor because it has bad geography.’

In this reading, Europe had certain climatic and physical geographic characteristics which put it at an initial advantage when compared to Africa. While this may be true, these two accounts (colonialism vs first nature geography) are somewhat at odds with each other. Was it Africa’s physical geography or its forcible conquest and subjugation which laid the basis for subsequent developmental underperformance, or a combination of the two? The World Bank leaves out the way in which economic power was politically expressed through colonial...