![]()

1

Foundations of a modern discipline

Antiquarians, historians, architects and archaeologists have long studied the architecture of the past. To look at architecture has meant looking at buildings and cities, artefacts and ruins, historical monuments and monumental sculptures, and to wonder how they came to be what they are. Architecture also offers a lasting mirror image of the people who commissioned, made and lived in and around it. When we already know something of them from other sources, understanding how and why they built enriches our knowledge of them. For as long as the architecture of the past has interested people in the present, the questions posed of it by scholars and students of all calibres have ranged wide. And so when architectural history emerged in German-speaking universities more than a century ago as part of the new discipline of art history, it borrowed tools, conceptual frameworks and imperatives from a range of places, but especially from archaeology, philology and architecture itself. Many of these tools, frameworks and imperatives have been adapted by successive generations of architectural historians to the extent that we can speak of them as now belonging properly to architectural history.

If architectural history is, in one sense, a democratic subject, available to anyone, it has nevertheless enjoyed privileged attention from its parent disciplines, which in turn have together shaped the modern academic discipline. Since the eighteenth century, for instance, architectural history has been taught to aspiring architects in schools and academies of architecture, grounding students in the past of their future profession, constructing and defending a canon of great works, and formulating and defining traditions – and the classical tradition above all. Art historians have long treated architecture as one of the visual arts, so that architects sat alongside painters, sculptors and printmakers – all artists. As the literary genre of the artist biography gave way to a ‘scientific’ art history, this convention remained firmly in place from the end of the nineteenth century as works of architecture became subject to formal and iconographic readings. Since the eighteenth century, archaeologists have scoured ancient building sites around the Mediterranean, Aegean, Adriatic and Red Seas. The architecture of the medieval era, too, has presented archaeologists with rich problems. In the British Isles and across northern and central Europe, study of the middle ages nourished early courses in the history of art and architecture and informed the first practices of architectural restoration and preservation. In Germany and Britain alike it underpinned a turn to Romanticism and nationalism. The nascent germanophone academic field of cultural history from the mid nineteenth century regarded architecture as evidence of culture, a resource equivalent to the history and ‘science’ of the visual and plastic arts. In this setting, architecture, as readily as printmaking, could help historians to understand the workings of culture and civilization. Buildings were documents that were best understood alongside other kinds of documents.

In their translation, many of these historiographical and analytical traditions now serve distinct ends for historians of architecture. Over the last century and a half, architectural history has emerged as a field of study in its own right. Some regard it as a discipline, with its own knowledge, questions and tools. Others understand the history of architecture as an inherently interdisciplinary venture. Others still treat architectural history as a specialization within the larger disciplines of architecture, art history, archaeology and history. Even those figures who have argued stringently for the disciplinary autonomy of architectural history find it difficult to isolate an incontestable core that remains unmuddied by multiform beginnings.

Defining architecture historically

Some scholars of architectural history defer to a canon of significant architects and buildings. Many would now rail against such a position, especially after the 1980s and 1990s and the upheavals of post-structuralist relativization that these decades witnessed across the humanities – and in the architectural humanities no less. The canon nonetheless has its uses, even if they are ultimately rhetorical.1 Writers still quote the aphorism with which Pevsner famously began An Outline of European Architecture (1943): ‘A bicycle shed is a building; Lincoln Cathedral is a piece of architecture.’2 Whether or not one trusts these categories and what Pevsner does with them, they (and he) offer a familiar distinction between what architecture is and what it is not. This then acts as a starting point for separating out the finer conceptual and categorical distinctions that shape what falls in and beyond the remit of architectural history. Much of the twentieth-century history of architectural historiography is informed by this basic distinction, its application to historical problems, the historical judgements on which it rests, and the disagreements that gather around it.

There is great disagreement, too, over the set of buildings deemed fundamental to an architect’s historical education, an art historian’s knowledge of architecture, an anthropologist’s study of traditional communities, a military historian’s knowledge of castellated fortresses, an economic historian’s appreciation of how building, urban planning and trade interact, or a church historian’s understanding of architecture’s expression of the liturgy or reaction to the dictates of the Curia – to name just a few examples. No one position has an inherently stronger claim than any other, even if the architect can claim privileged insight into historical works. Architecture is sometimes studied in its own terms, but is just as often tabled as evidence for problems that are not architectural in nature. A survey of houses built in the 1920s can tell us much about social and domestic arrangements, the structuring of class and gender roles, and geographical differences on these issues. They can tell us about technology and its repercussions for domestic life, patterns of consumption and standards of taste. Where architecture might hold clues for the historian of society or technology, an architectural historian may wish to know how a ‘traditional’ house might have made way for modernist planning, or for the mass production of building parts. The architecture thus becomes evidence of itself, of the decisions and awareness of its designer and/or builder. Is a house exemplary, or symptomatic? Is it important architecturally, or historically?

Architectural historians have tended to enjoy these kinds of ambiguities. Pulling architecture in one disciplinary direction and another means that architecture as a subject sustains perpetual scrutiny from many angles, which in turn feeds back into the knowledge base of architectural historians to the subject’s further enrichment. On the question of how to ‘do’ architectural history, there is no fundamental agreement to be found in and between conferences, universities or any other infrastructure supporting its discussion. This reflects the different patterns through which the knowledge traditions we are about to consider gave modern architectural history a specific scope and structure in each iteration of its appearance.

These observations do not add up to a systematic account of architectural historiography before the emergence of a ‘modern’ architectural history. They are meant to point, rather, towards a matrix of conceptual and methodological problems inherited by architectural history as it became more clearly differentiated from other modes of historical study from early in the twentieth century. This new field’s inheritance from the various strains in which historical knowledge of architecture was understood and transmitted was itself institutionalized, contested and developed. Historiographical issues of influence, style, taxonomy, critical categories (plan, space, form, etc.), progress and change, restoration and preservation, instrumentality, analytical units, the permeability of historical knowledge – these categories shaped the development of architecture’s historiography in the first century of academic architectural history. But in doing so, they gave new form to a much longer tradition of finding lessons, trajectories and narratives in architecture’s past, and to defining architecture itself in historical terms.

Architectural history as the architect’s patrimony

Architectural theory in antiquity

The oldest surviving account of architecture’s history was penned in the last decades of the first century BC by Vitruvius, an architect and engineer who, seeking to secure an imperial pension, documented Roman building practices and outlined their general principles. After 2,000 years, we cannot expect much of what Vitruvius understood of architecture to remain relevant to present-day readers. Still, the architect of his De architectura understood building materials and their properties, methods of construction, planning and siting, as well as principles of harmonics, heating, sunlight and colour. He understood that architecture relied on ‘Order, Arrangement, Eurythmy, Symmetry, Propriety, and Economy’.3 And he understood that the values of durability, convenience and beauty stood behind worthy buildings.4 Vitruvius claimed to lay down the rules of architecture as they had been practised up to and during his time to enable Caesar Augustus (most likely) ‘to have personal knowledge of the quality both of existing buildings and those which are yet to be constructed’.5 His ambitions, then, were twofold. First, he sought to explain the formal, semantic and pragmatic dimensions of the buildings of the past. Second, he sought to identify the principles derived from their study that could help architects make good architecture. As he wrote to his Emperor, by understanding the principles that had resulted in superior buildings in Greece and Rome he had become a better judge of architecture in his own time. An architect in the Emperor’s service could take Vitruvius’ observations and apply them to the conception and construction of new buildings and monuments.

Vitruvius wrote during a transitional phase in the history of Roman architecture, when native principles of architectural composition and engineering governing the form, disposition and decoration of buildings began accommodating a fashion for the architecture of Greece and Asia Minor and from the golden fifth century of the Greek Empire. Vitruvius’ treatise is Roman, but it is also a Roman reflection on the historical architecture of Ionian and mainland Greece at a moment in which Romans placed great worth on the art and architecture of that territory, from around the start of the second century BC. Rome knew the architecture of many distant lands, from Spain and Britain to Armenia and Syria, but in the subjugation of Greece, Rome adapted its artful approach to building. Vitruvius’ Rome is a hybrid architectural culture: of Rome and its territories. Rome welcomed the powerful and permanent influence of Hellenic culture. This did Rome no harm: through respect for and emulation of Greece – the greater historical authority, the originator of artfully building with columns, beams and pediments – Rome’s architecture, too, became a worthy exemplar.

From shelter to architecture

De architectura on two occasions describes the origins of the Roman architecture of Vitruvius’ day. In the primordial past (book II), people gathered around fire, found a basis for communication and formed communities, which in turn required shelter. The Greeks (book IV) gave order and meaning to the habits and customs of shelter and community, and the authority with which they did so demanded emulation. Their architecture embodied this order, and their architects developed a language for architecture, which the Romans then imitated, adapted and elaborated. On the basis of the Greek model, as presented by Vitruvius, architects skilfully used systems of proportion and decoration to achieve beautiful, fitting and well-disposed buildings.

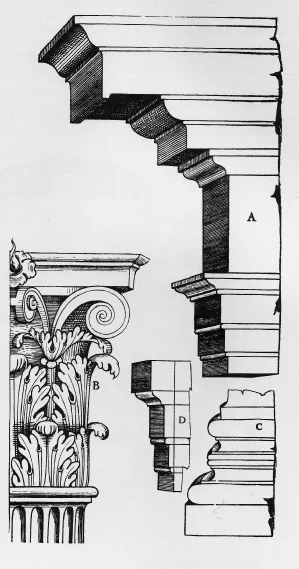

Consider how Vitruvius presents the three Greek orders (Doric, Ionic and Corinthian) in book IV (1.8). ‘Posterity’, he writes, found ‘pleasure in more slender proportions’. Hence the Doric column is less slender than that of the Ionians (commonly called the Ionic order, but increasingly also the Ionian), and the Corinthian order, which imitates ‘the slenderness of a maiden,’ is the most fine of all, ‘for the outlines and limbs of maidens, being more slender on account of their tender years, admit of prettier effects in the way of adornment’.6 Early modern treatises regarded Vitruvius’ rules as hard and fast. In their study of the extant monuments of antiquity, Sebastiano Serlio (1475–1554) and Andrea Palladio (1508–80) were troubled by the apparent freedom with which Roman architects used the orders: their proportions as much as their decorations. Nevertheless, Vitruvius linked the proportions of the Greek orders to the human body (man, woman and maiden, respectively), which in turn determined their application. The palace of a military officer would, for instance, employ the robust Doric order rather than the delicate Corinthian; the Temples of Vesta, both at Tivoli and in the Foro Romano, employ the Corinthian order rather than the more mature Ionic or the heavy Doric.

Documentation versus advocacy

De architectura illustrates a way of writing about architecture that mixes documentation and advocacy. By imitating this ancient example, architectural treatises written from the fifteenth century onwards assumed this role too. It is difficult to measure, from our present-day perspective, how important Vitruvius’ observations or his sometimes heavy-handed rhetoric were in his own time. It seems clear that, from the fall of the Roman Empire until the early phases of what we now call the Renaissance, his treatise was not an important source of instruction about building. When medieval scholars read De architectura it was as a classical text, alongside Livy or Plotinus, or for its insights into Roman views on ...