![]()

1

Elements of the Theory of Structuration

In offering a preliminary exposition of the main concepts of structuration theory1* i t will be useful to begin from the divisions which have separated functionalism (including systems theory) and structuralism on the one hand from hermeneutics and the various forms of ‘interpretative sociology’ on the other. Functionalism and structuralism have some notable similarities, in spite of the otherwise marked contrasts that exist between them. Both tend to express a naturalistic standpoint, and both are inclined towards objectivism. Functionalist thought, from Comte onwards, has looked particularly towards biology as the science providing the closest and most compatible model for social science. Biology has been taken to provide a guide to conceptualizing the structure and the functioning of social systems and to analysing processes of evolution via mechanisms of adaptation. Structuralist thought, especially in the writings of Lévi-Strauss, has been hostile to evolutionism and free from biological analogies. Here the homology between social and natural science is primarily a cognitive one in so far as each is supposed to express similar features of the overall constitution of mind. Both structuralism and functionalism strongly emphasize the pre-eminence of the social whole over its individual parts (i.e., its constituent actors, human subjects).

In hermeneutic traditions of thought, of course, the social and natural sciences are regarded as radically discrepant. Hermeneutics has been the home of that ‘humanism’ to which structuralists have been so strongly and persistently opposed. In hermeneutic thought, such as presented by Dilthey, the gulf between subject and social object is at its widest. Subjectivity is the preconstituted centre of the experience of culture and history and as such provides the basic foundation of the social or human sciences. Outside the realm of subjective experience, and alien to it, lies the material world, governed by impersonal relations of cause and effect. Whereas for those schools of thought which tend towards naturalism subjectivity has been regarded as something of a mystery, or almost a residual phenomenon, for hermeneutics it is the world of nature which is opaque – which, unlike human activity, can be grasped only from the outside. In interpretative sociologies, action and meaning are accorded primacy in the explication of human conduct; structural concepts are not notably prominent, and there is not much talk of constraint. For functionalism and structuralism, however, structure (in the divergent senses attributed to that concept) has primacy over action, and the constraining qualities of structure are strongly accentuated.

The differences between these perspectives on social science have often been taken to be epistemological, whereas they are in fact also ontological. What is at issue is how the concepts of action, meaning and subjectivity should be specified and how they might relate to notions of structure and constraint. If interpretative sociologies are founded, as it were, upon an imperialism of the subject, functionalism and structuralism propose an imperialism of the social object. One of my principal ambitions in the formulation of structuration theory is to put an end to each of these empire-building endeavours. The basic domain of study of the social sciences, according to the theory of structuration, is neither the experience of the individual actor, nor the existence of any form of societal totality, but social practices ordered across space and time. Human social activities, like some self-reproducing items in nature, are recursive. That is to say, they are not brought into being by social actors but continually recreated by them via the very means whereby they express themselves as actors. In and through their activities agents reproduce the conditions that make these activities possible. However, the sort of ‘knowledgeability’ displayed in nature, in the form of coded programmes, is distant from the cognitive skills displayed by human agents. It is in the conceptualizing of human knowledgeability and its involvement in action that I seek to appropriate some of the major contributions of interpretative sociologies. In structuration theory a hermeneutic starting-point is accepted in so far as it is acknowledged that the description of human activities demands a familiarity with the forms of life expressed in those activities.

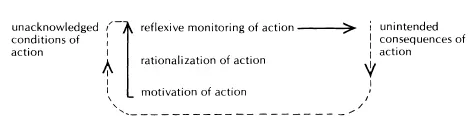

It is the specifically reflexive form of the knowledgeability of human agents that is most deeply involved in the recursive ordering of social practices. Continuity of practices presumes reflexivity, but reflexivity in turn is possible only because of the continuity of practices that makes them distinctively ‘the same’ across space and time. ‘Reflexivity’ hence should be understood not merely as ‘self-consciousness’ but as the monitored character of the ongoing flow of social life. To be a human being is to be a purposive agent, who both has reasons for his or her activities and is able, if asked, to elaborate discursively upon those reasons (including lying about them). But terms such as ‘purpose’ or ‘intention’, ‘reason’, ‘motive’ and so on have to be treated with caution, since their usage in the philosophical literature has very often been associated with a hermeneutical voluntarism, and because they extricate human action from the contextuality of time-space. Human action occurs as a durée, a continuous flow of conduct, as does cognition. Purposive action is not composed of an aggregate or series of separate intentions, reasons and motives. Thus it is useful to speak of reflexivity as grounded in the continuous monitoring of action which human beings display and expect others to display. The reflexive monitoring of action depends upon rationalization, understood here as a process rather than a state and as inherently involved in the competence of agents. An ontology of time-space as constitutive of social practices is basic to the conception of structuration, which begins from temporality and thus, in one sense, ‘history’.

This approach can draw only sparingly upon the analytical philosophy of action, as ‘action’ is ordinarily portrayed by most contemporary Anglo-American writers. ‘Action’ is not a combination of ‘acts’: ‘acts’ are constituted only by a discursive moment of attention to the durée of lived-through experience. Nor can ‘action’ be discussed in separation from the body, its mediations with the surrounding world and the coherence of an acting self. What I call a stratification model of the acting self involves treating the reflexive monitoring, rationalization and motivation of action as embedded sets of processes.2 The rationalization of action, referring to ‘intentionality’ as process, is, like the other two dimensions, a routine characteristic of human conduct, carried on in a taken-for-granted fashion. In circumstances of interaction – encounters and episodes – the reflexive monitoring of action typically, and again routinely, incorporates the monitoring of the setting of such interaction. As I shall indicate subsequently, this phenomenon is basic to the interpolation of action within the time-space relations of what I shall call co-presence. The rationalization of action, within the diversity of circumstances of interaction, is the principal basis upon which the generalized ‘competence’ of actors is evaluated by others. It should be clear, however, that the tendency of some philosophers to equate reasons with ‘normative commitments’ should be resisted: such commitments comprise only one sector of the rationalization of action. If this is not understood, we fail to understand that norms figure as ‘factual’ boundaries of social life, to which a variety of manipulative attitudes are possible. One aspect of such attitudes, although a relatively superficial one, is to be found in the commonplace observation that the reasons actors offer discursively for what they do may diverge from the rationalization of action as actually involved in the stream of conduct of those actors.

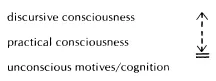

This circumstance has been a frequent source of worry to philosophers and observers of the social scene – for how can we be sure that people do not dissimulate concerning the reasons for their activities? But it is of relatively little interest compared with the wide ‘grey areas’ that exist between two strata of processes not accessible to the discursive consciousness of actors. The vast bulk of the ‘stocks of knowledge’, in Schutz’s phrase, or what I prefer to call the mutual knowledge incorporated in encounters, is not directly accessible to the consciousness of actors. Most such knowledge is practical in character: it is inherent in the capability to ‘go on’ within the routines of social life. The line between discursive and practical consciousness is fluctuating and permeable, both in the experience of the individual agent and as regards comparisons between actors in different contexts of social activity. There is no bar between these, however, as there is between the unconscious and discursive consciousness. The unconscious includes those forms of cognition and impulsion which are either wholly repressed from consciousness or appear in consciousness only in distorted form. Unconscious motivational components of action, as psychoanalytic theory suggests, have an internal hierarchy of their own, a hierarchy which expresses the ‘depth’ of the life history of the individual actor. In saying this I do not imply an uncritical acceptance of the key theorems of Freud’s writings. We should guard against two forms of reductionism which those writings suggest or foster. One is a reductive conception of institutions which, in seeking to show the foundation of institutions in the unconscious, fails to leave sufficient play for the operation of autonomous social forces. The second is a reductive theory of consciousness which, wanting to show how much of social life is governed by dark currents outside the scope of actors’ awareness, cannot adequately grasp the level of control which agents are characteristically able to sustain reflexively over their conduct.

The Agent, Agency

The stratification model of the agent can be represented as in figure 1. The reflexive monitoring of activity is a chronic feature of everyday action and involves the conduct not just of the individual but also of others. That is to say, actors not only monitor continuously the flow of their activities and expect others to do the same for their own; they also routinely monitor aspects, social and physical, of the contexts in which they move. By the rationalization of action, I mean that actors – also routinely and for the most part without fuss – maintain a continuing ‘theoretical understanding’ of the grounds of their activity. As I have mentioned, having such an understanding should not be equated with the discursive giving of reasons for particular items of conduct, nor even with the capability of specifying such reasons discursively. However, it is expected by competent agents of others – and is the main criterion of competence applied in day-to-day conduct – that actors will usually be able to explain most of what they do, if asked. Questions often posed about intentions and reasons by philosophers are normally only put by lay actors either when some piece of conduct is specifically puzzling or when there is a ‘lapse’ or fracture in competency which might in fact be an intended one. Thus we will not ordinarily ask another person why he or she engages in an activity which is conventional for the group or culture of which that individual is a member. Neither will we ordinarily ask for an explanation if there occurs a lapse for which it seems unlikely the agent can be held responsible, such as slips in bodily management (see the discussion of ‘Oops!’, pp. 81–3) or slips of the tongue. If Freud is correct, however, such phenomena might have a rationale to them, although this is only rarely realized either by the perpetrators of such slips or by others who witness them (see pp. 94–104).

Figure 1

I distinguish the reflexive monitoring and rationalization of action from its motivation. If reasons refer to the grounds of action, motives refer to the wants which prompt it. However, motivation is not as directly bound up with the continuity of action as are its reflexive monitoring or rationalization. Motivation refers to potential for action rather than to the mode in which action is chronically carried on by the agent. Motives tend to have a direct purchase on action only in relatively unusual circumstances, situations which in some way break with the routine. For the most part motives supply overall plans or programmes – ‘projects’, in Schutz’s term – within which a range of conduct is enacted. Much of our day-to-day conduct is not directly motivated.

While competent actors can nearly always report discursively about their intentions in, and reasons for, acting as they do, they cannot necessarily do so of their motives. Unconscious motivation is a significant feature of human conduct, although I shall later indicate some reservations about Freud’s interpretation of the nature of the unconscious. The notion of practical consciousness is fundamental to structuration theory. It is that characteristic of the human agent or subject to which structuralism has been particularly blind.3 But so have other types of objectivist thought. Only in phenomenology and ethnomethodology, within sociological traditions, do we find detailed and subtle treatments of the nature of practical consciousness. Indeed, it is these schools of thought, together with ordinary language philosophy, which have been responsible for making clear the shortcomings of orthodox social scientific theories in this respect. I do not intend the distinction between discursive and practical consciousness to be a rigid and impermeable one. On the contrary, the division between the two can be altered by many aspects of the agent’s socialization and learning experiences. Between discursive and practical consciousness there is no bar; there are only the differences between what can be said and what is characteristically simply done. However, there are barriers, centred principally upon repression, between discursive consciousness and the unconscious.

As explained elsewhere in the book, I offer these concepts in place of the traditional psychoanalytic triad of ego, super-ego and id. The Freudian distinction of ego and id cannot easily cope with the analysis of practical consciousness, which lacks a theoretical home in psychoanalytic theory as in the other types of social thought previously indicated. The concept of ‘pre-conscious’ is perhaps the closest notion to practical consciousness in the conceptual repertoire of psychoanalysis but, as ordinarily used, clearly means something different. In place of the ‘ego’, it is preferable to speak of the ‘I’ (as, of course, Freud did in the original German). This usage does not prevent anthropomorphism, in which the ego is pictured as a sort of mini-agent; but it does at least help to begin to remedy it. The use of ‘I’ develops out of, and is thereafter associated with, the positioning of the agent in social encounters. As a term of a predicative sort, it is ‘empty’ of content, as compared with the richness of the actor’s self-descriptions involved with ‘me’. Mastery of ‘I’, ‘me’, ‘you’ relations, as applied reflexively in d...