During the riots of 2005, a film became extremely popular among the youth of the working-class neighborhoods where I was conducting my study of the police. Released a year previously in cinemas, to no great excitement, Banlieue 13 was now circulating in the form of pirate DVDs that they passed from one to another, with approving commentaries.1 The pleasure they took in watching it certainly had a lot to do with the breathless pace of episodes as violent as they were improbable, and with the art of acrobatic movement from place to place (“parkour”) practiced by the characters who made light work of urban obstacles. But many of them clearly saw, in this futuristic film, a fantasy echo of what they were living during that period, albeit more on their television screens than in their immediate environment. “Paris 2010. Faced with the unstoppable rise in crime in some banlieues, the government authorizes construction of an isolation wall around high-risk housing projects,” read the DVD insert.

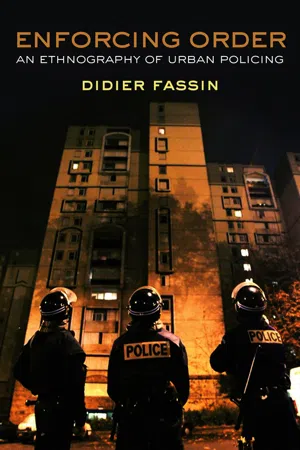

While the plot, which involves an officer from a special intervention unit that has infiltrated mafia gangs being tasked with disarming a weapon of mass destruction, might seem far-fetched, the images of projects abandoned to the rule of gangs, around which walls have been erected to contain a population that has become undesirable, offered a seductive, if caricatured, reference to the segregation at work in the banlieues.2 The title also pointed to this convergence between fiction and reality, the number 13 evoking the 93 postal code of the Seine-Saint-Denis département where the riots had begun a few weeks earlier.3 The opening scenes showed burned-out cars, graffiti-tagged walls, broken-down entry phones, dilapidated building stairwells, teenagers wearing hooded sweatshirts, and threatening heavily armed helmeted police. In an implausible final confession, the minister of the interior admitted that he hatched the extermination plan to rid society of the “scum” of these neighborhoods. By remarkable coincidence or premonition, given that the film had been shot long before Nicolas Sarkozy's notorious visits, as minister of the interior, to the “Quatre Mille” of La Courneuve and later to the “Dalle d’Argenteuil,” two large housing projects, this language was identical to that subsequently used by the character's real-life alter ego.4 The ending of the movie, where the housing project destined for demolition and its residents condemned to disappear were miraculously saved by a hero who chose to remain in the walled neighborhood where he claimed to feel at home, despite offers to get him out, was far from the more humdrum and less happy experience of its young viewers. But after I had, at the start of the unrest, accompanied the anticrime squad in their night-time activities, supported by the riot police companies who were called in as reinforcement, and protected by helicopters shining powerful searchlights over the apartment blocks, for me there was something troubling about the parallel I involuntarily drew, as obviously the youngsters did, with some of the scenes in the film.

“It's a shame you weren't there. It was practically war out there!” one of the members of the anticrime squad exclaimed to me excitedly when he saw me again in January 2006, after several weeks of absence. He told me how, for several days, he and his colleagues wore bulletproof vests, donned riot helmets and patrolled with Flash-Balls. It is true that the prime minister's declaration of a state of emergency on November 8, 2005 – paradoxically, at the point when the vehicle fires and arresting of rioters were beginning to die down – had thrown the work of the police into unusually sharp focus, and many of them suddenly felt themselves masters of the place. It was the first time since the Algerian War of Independence in the 1950s and early 1960s that a government in France had recourse to such an exceptional measure, and the use of this legal instrument for the control of people, many of whom originated from North Africa or sub-Saharan Africa, gave a particular tone to the mass police operation in the projects. Riot police vans patrolled the streets or parked at strategic points. Gendarmerie helicopters equipped with infrared cameras circled low over the city. Although there was no curfew in the areas where I was carrying out my study, the neighborhoods were deserted as soon as night fell, sporadically lit up by a burning vehicle.

Yet in this district, which was deemed at risk and often mentioned in media stories and the Ministry's reports, there were few confrontations. On November 23, 2005, when the number of vehicles set on fire in France had fallen below the level used to define so-called “normal nights” (that is, about 90), I asked the chief of police how these weeks of disorder had been. He replied smiling: “What riots? What are you talking about? We need to know what it is we're counting here: cars or violence? If we're talking cars, there were a few dozen. If we're talking about violence, there was hardly any. But the media only counted the burned-out cars. It was actually very calm around here.” Keen to share his experience with me, he stated how, several years earlier, following the death of a youth in a police car chase in a housing project, a “real riot” broke out in the town where he was then a young deputy commissioner: “That was really hot. I'd even say it bordered on insurrection!” By contrast, the events he had just witnessed seemed to him to have been highly exaggerated by the communications from the Ministry and the images broadcast on television. Despite what his officers were feverishly trying to tell themselves, for him, the war of the projects had never taken place.

There is a remarkable contrast between these two visions of the events of 2005 – “practically war” for some, “very calm” for others – in a city where, after one night in which a number of cars were burnt in a housing project but no arrests were made, there had ultimately been few incidents other than isolated fires in private cars and public buildings. One could, of course, as beat officers often do, attribute this difference in perspective to the gap between those involved on the ground and those commanding from their offices, between a rank-and-file facing the everyday reality of the neighborhoods and a hierarchy gathering information only from statistics, or even between the former telling the truth and the latter euphemizing it in front of a stranger. But this would be to misunderstand the image officers have of the social situation in which they are involved, and the consequences this worldview has on the way they police these neighborhoods.

Rather than the objective analysis of events offered by the commissioner, we need to grasp their subjective apprehension by the officer of the anticrime squad – not because it would be more faithful to what did happen but for what it tells us of the vision and spirit of the police operating in the banlieues. It is his excitement at what this agent sees as a state of war that it is necessary to comprehend. The episode of the riots in fact crystallizes a representation of the banlieues that portrays them as territories constantly at risk not only of falling prey to disorder but also of slipping out of the grasp of law enforcement. The trope of “no-go zones” into which the police no longer dare to venture and where they need to re-establish themselves is, with rare exceptions, much less a description of reality than a rallying slogan based on a fantasy of danger as well as reconquest, the image of danger magnifying the courage of those who face it, and that of reconquest justifying the action aimed at realizing it. In the district where I conducted my research, the police had no problem in going wherever they wanted – and much more often in projects reputed to be problematic than elsewhere – but the talk of “neighborhoods” that must not be left to the “hooligans” nevertheless continued to circulate, as if the defense of the “territories of the Republic,” to use the officials’ language, could serve as grounds for “pacifying” the projects.

An adolescent told me that, the day after a vehicle fire in his project, the sergeant major heading the anticrime squad spoke to a group of youngsters gathered in a square in the late afternoon: “If one more car is set on fire here and I catch the guy who did it, I'll kill him and bury him.” The fear inspired by this officer, well known in the area, made his threats – if not literally, at least symbolically – plausible. There is nothing surprising about this story, and I often heard similar statements myself. A beat officer laughed as we watched a video of youths being questioned that was then circulating widely online: “Everything started OK, but for once when it was looking good for us there's that cop that says to the motherfucker: ‘If you carry on like that you're going to burn on the electric cables like your pals.’ ” The macabre allusion to the tragic event that sparked the riots, and my informant's amused response, revealed the extent to which the violence of the words seemed normal in the police world. For him, as for a number of his colleagues, working in the banlieues meant operating in hostile terrain where the residents were seen as enemies who would miss no chance to attack them. If, exceptionally, they did happen to get “stoned” by youngsters, they knew they could return with reinforcements to exact reprisals that would affect the whole of the neighborhood. Their senior officers had great difficulty in preventing them from doing this – despite their genuine desire to do so. A commissioner told me of the problem she had experienced in restraining her troops who, after coming under attack in a project, wanted to intervene en masse to “establish their presence in the territory.” She had to use all her authority to prevent them from “putting the project to fire and sword,” since it was so much simpler to come back the next morning, she added, when tempers would have cooled, to conduct the necessary questionings and arrests. Usually, however, superiors did not intervene to inhibit such operations, either because they saw them as inevitable, or because they were only told about them afterwards. They then had to offer a public justification for them and demonstrate support to their officers, while concurrently trying to conduct an internal inquiry into the most glaring infractions.

Six months before the events at the end of 2005, certain incidents in one of the reputedly problematic neighborhoods in the town seemed to me richly informative about the sequence of events that could lead to what the police unions later described as a “riot,” but which a French engineer living in the neighborhood compared to a “ratonnade,” that is, a form of ethnic cleansing against Arabs. I had accompanied uniformed officers on foot patrol or in marked vehicles several times in this neighborhood, made up of two- or three-story blocks, pleasingly designed, set amid green spaces. The contrast between its peaceful appearance and its bad reputation was remarkable. A resident, a member of a small Jesuit community, told me of the patient efforts of the tenants’ association to induce respect for the environment and improve relations within the community: graffiti had disappeared from the walls, the acts of petty vandalism had diminished, a block party had just been held in the park adjacent to the apartments, donations had been collected from residents to fund a weekend by the sea for a group of teenagers. But the social reality as he described it was far from idyllic: unemployment was high among the youth, and everyone knew that drugs were being dealt. As to the relationship between the local population and law enforcement, it was consistently deteriorating. There were constant stops and frisks, always targeting the same young men, which had no effect on illegal activities but raised tensions. When a resident called the police about a mundane problem such as a noisy gathering in a square, the response was so brutal and, ultimately, counterproductive that most had given up making complaints. “The atmosphere between residents and the police has become horrible,” my informant concluded. I recognized this myself as I accompanied officers in the afternoon and evening, and witnessed their interactions with young people during checks and searches. The aggressive attitude and scorn of the law enforcement agents was met with hostile silence and mute rage.

In this tense atmosphere, a resident called the police one evening in May to complain of an all-terrain vehicle being driven in the adjacent park and causing noise pollution. Three uniformed officers turned up to stop the young driver, who attempted to flee but fell off his quad bike, without hurting himself. The accident allowed the police to catch him and bring him under control. Seeing their friend in difficulty, a dozen teenagers who were in the vicinity rushed to his rescue and formed a threatening circle around the officers, who, outnumbered by their opponents, had to retreat and call for reinforcements. Once alerted, all the uniformed and anticrime squad patrols active that night swiftly arrived, overrunning the project as they searched for suspects. The police deployment was striking and brutal. On that spring evening, many children were at the playground, the youngest under the watchful gaze of their parents. In the ensuing disorder, a number were pushed. One officer, aiming to intimidate a nine-year-old he had judged insolent, put the barrel of his Flash-Ball to the boy's head. A mother who tried to shield her children was questioned aggressively. Horrified residents looked out of their windows as the police stormed the neighborhood paths and the stairways of the buildings. The door to the apartment where the family of one of the suspects lived was broken down, the furniture overturned and several persons hurt, including the teenage sister of the young man being sought. She was doing her homework, and, as she came out of her room at the wrong moment, she was roughed up, ending the night in the hospital with a broken arm and a neck injury. Her brother – a well-known drug dealer – was finally arrested but released a few hours later, when the police realized he was blind and could not therefore have been involved in the initial altercation.

The Alliance police union, known to be close to the right-wing government, spoke of “attacks of indescribable savagery” against the police, making reference to officers “set on and seriously injured.” The Human Rights League (Ligue des droits de l’homme) local representatives wrote to the state prosecutor denouncing “racist and sexist insults that particularly shocked the local residents because death threats were added.” The following day, the town hall organized a meeting with residents’ representatives, who condemned “the disproportion between the incidents and the police response, and the stigmatization of non-French residents,” while the mayor met the commissioner to discuss with him the “vicious spiral” of violence on both sides, the “gulf between law enforcement agents and inhabitants,” and his “anxiety as to whether the police have the will to protect local residents’ safety.”5 When I discussed these incidents with the mayor, he said he was shocked by the brutality of the operation, which had affected all residents indiscriminately. Later I met one of the leaders of the tenants’ association, who told me that such incidents wiped out months of patient efforts to improve life in the neighborhood, and even led residents to see criminals as victims. The commissioner, for his part, protested that once again the police were being blamed. He criticized the mayor, whom he suspected of playing politics with the affair, and accused the tenants’ association of adding fuel to the flames. He could not imagine the former, as head of the municipal police, and the latter, which in its own way was committed to maintaining order, as allies. He regarded them as adversaries with whom it was necessary to compromise, but certainly not collaborate. The officers I spoke to during the following days admitted that the serious injuries evoked by the union amounted to one of the three who had chased the driver of the all-terrain vehicle spraining his ankle. They nevertheless considered their brutal intervention justified, because it had shown the residents that the police would not be pushed around. They believed they had been victims of an “ambush,” a term increasingly used at the time to describe confrontations with youth in the projects, with the assumption of premeditation and criminal intention. In the face of what they saw as a sort of urban guerrilla war, these punitive raids seemed to them the only way to bring rebellious groups “to heel.”

Such bellicose practices are not isolated incidents. They echo the discourse that has been systematically used by the authorities in speaking of the banlieues since the early 2000s, whether in calling for “war against crime,” “war without mercy against criminality,” “war on drug dealers” or “war on violent gangs.”6 The use of this rhetoric legitimizes not only the police's views of the situation facing them, but also the way they work to impose order. This is what Egon Bittner argued in relation to the routinization of the discourse of war on crime in the US in the 1960s: “The price we are prepared to pay to defeat crime and disorder does not include visiting incidental suffering on innocents. Not to observe this stricture would turn crime control into a handmaiden of crime.”7 The warlike rhetoric has a cost in terms of democracy, leading to excesses that affect not only the criminals targeted, but also, through collateral damage, citizens who have done nothing wrong. In France, discussion of police operations has focused recently on the weapons used by the youth in the projects, suggesting an unavoidable deadly escalation that justifies the excessive equipping of officers with so-called “sub-lethal” weapons (Flash-Balls and Tasers), which can in fact have serious consequences.8 The use of martial vocabulary, to which is added the language of stigmatization (“scum”) and eradication (“cleansing”), radicalizes a way of talking not so much about problems and individuals as, by association, about areas and populations – precisely those in which economic disparities, social hardships and racial discrimination are accumulated – and it not only radicalizes it, but also normalizes it at the highest level of state. Thus, via a rhetoric that sidesteps the issues o...