![]()

1

Introduction

To somewhat alter a phrase from Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, “A specter is haunting advanced industrial countries and it is structural unemployment.” In Europe, Spain and Greece are facing unemployment rates over 25 percent. The decline in jobs that comes and goes with the economic ups and downs of the business cycle – cyclical unemployment – is being supplanted by more permanent and disrupting unemployment that threatens the working and middle classes. A 2012 Pew survey of 1,297 Americans says that in the preceding fifteen years, the middle class had “shrunk in size, fallen backward in income and wealth, and shed some – but by no means all – of its characteristic faith in the future” (Pew, 2012:1). Michael Gibbs says that the American “middle class is on the verge of extinction” (2010:B8). The economic recovery after 2001 was unusually weak in providing employment, and since 2004, observers have been increasingly talking about “jobless recoveries”− when an economy experiences growth in GDP while employment stagnates. While the stock market has recovered from the “great recession” of 2008, employment has not. This collapse was considered to be cyclical by many, but much of this landslide of unemployment is clearly structural. The recovery of profits and corporate performance has not resurrected the job market.

Structural unemployment and futile job searches are common, and the most recent generation of young job seekers is being called “the Recession Generation” or “Generation R.” There are two versions of Generation R: underworked 20-somethings cannot get their first job and live at home, and overworked 20-somethings hang on to their jobs but have to do twice as much work because employers have cut their workforce to the bone (Schott, 2010; Godofsky et al., 2010; Newman, 1999, 2012). In response to these jobless recoveries, this book explains the four causes of structural unemployment and rising inequality, and then proposes policies to alleviate joblessness.

In our view, the four causes of structural unemployment and downward mobility are diverse and not commonly put together in the same breath. First, the most discussed features of unemployment come from “skill mismatches” caused by the shift from manufacturing to service jobs. Blue-collar skills are a poor fit with white-collar or service jobs. But there is more going on here than a simple need for retraining. Second, corporate offshoring in search of lower wages has moved large numbers of jobs to China, India, and other countries, and this has decimated manufacturing and some white-collar jobs. Offshoring requires massive amounts of direct foreign investment and a consulting industry that backs it up. It is especially caused by two corporate forms of lean production. Third, technology in the form of containerships, computers, and automation has replaced many jobs. The web has devastated jobs in newspapers, magazines, the postal service, and travel agencies. The internet also aids offshoring because it allows people to do information-intensive jobs from anywhere in the world. Automation and robotics reduce jobs on assembly lines throughout the world, and create only a few more jobs in designing and maintaining equipment. And although information technology also leads to new jobs, it does not produce enough jobs in the short term to balance the losses. Fourth, instability in global finance creates pressures for offshoring and makes recessions more frequent and longer. This intensifies the previous three factors by causing downturns that become structural as they increase the duration of unemployment. In sum, new jobs emerge in less-developed countries (LDCs), but these four forces destroy jobs in advanced industrialized countries with an instantaneous, worldwide system of communication.

Economic, Political Economy and Institutional Explanations

There are some differences between the way we use the term “structural unemployment” and the way economists generally use it. We take a macro-sociological approach based on a critical view of political economy. The strength of the economic approach is the creation of a tightly linked theory with a narrow focus on a limited number of variables. In a sense, most economic analyses of unemployment are generally limited to job vacancies, inflation, and economic growth, sometimes adding investment (especially when they move to explaining growth rather than jobs) (Daly et al., 2012; Acemoglu, 2009). The results seem to be tightly focused on mismatch – the first of our four explanations. While this explanation has some validity, sole reliance on it often leads to “blaming the victim” – it's the unemployed workers' fault that they have not retrained or chosen a better occupation. As a result, this approach has little to say about outsourcing, offshoring, ancillary technologies, and the detrimental effects of financialization on unemployment.1

Our wider view of structural unemployment builds on some of the mismatch analysis, but focuses more on the conflict between denationalized transnational corporations and employees in advanced industrialized countries (AICs). This is partially a class-conflict approach using elite or neo-Marxist theory with offshore-based profit taking, and an institutional or Weberian analysis of multination states struggling to maintain control of corporations and protect their citizens in a global economic environment. As one can see, the economic results of the last few decades have favored transnational corporations, with their high profits, and the upper classes getting a historically high proportion of income and especially wealth (Goldstein, 2012). Former middle-class citizens have suffered greater unemployment and then a downward shift to lower-paid jobs. In some ways a new social contract is in the initial stages of being forged, with the powerful transnational corporations having the upper hand at this point. This is why explanations that do not use a wider lens − focusing on financialization, the declining middle class, growing inequality, and transnational corporations − are quite myopic. We will discuss economic studies that we believe show that a structural shift has occurred, but our explanations will be much broader than most of these analyses. For instance, in the aftermath of the recession of 2008, Daly et al. say that “a better understanding of the determinants of job creation in the aftermath of recession is crucial” (2012:24). Thus, our intent is to explain unemployment with three additional arguments involving a panorama of American workers in a new and complex division of labor.

In the next sections we discuss (1) the definitions, levels, and types of unemployment, with a focus on structural unemployment, including the Beveridge and Phillips curves, the duration of unemployment, and the stigma involved in current increases in the duration of unemployment; (2) the impact of unemployment on inequality, which starts with unemployment and leads to decreasing one's expectations of work to the lower-level segments of the labor market; and (3) the four factors that cause structural unemployment – the shift to service jobs and skill mismatches, outsourcing and offshoring, new technologies, and structural financialization – which is the main focus of this book; and we end with (4) our governmental policy recommendations to alleviate structural unemployment.

Definitions, Levels, and Types of Unemployment

Unemployment is generally defined as the number of persons who are ready and willing to work who cannot find a job. The unemployment rate consists of those persons who are unemployed divided by the total labor force, which includes the unemployed. It is important to note that if a person is not ready and willing to work, which means that they are not actively searching for a job, then that person is considered to be out of the labor force and is therefore neither employed nor unemployed. These “discouraged workers” are removed from the unemployment figures and the overall labor force. People can leave the labor force by routes including retiring early, going on disability, working in the underground or illegal economy, or simply living upon the contributions of others (e.g., family, friends, or the government).

There are two methods for collecting unemployment figures. One method uses a sample survey of the population to find out the number of unemployed and those who are working. The other method relies on the administrative records of the employment service or other agency that gives out unemployment compensation payments and often gives job search advice. The survey research method of collecting the data is generally considered to be the most accurate way to determine unemployment rates because the administrative record method can miss people who do not want to receive unemployment compensation (Davis et al., 2010). Often those people who anticipate only a short stay on unemployment fall into this category, although there are a few people who are ideologically opposed to the idea of government and will refuse their unemployment compensation payments and use their retirement or other savings to tide them over during various bouts of unemployment.

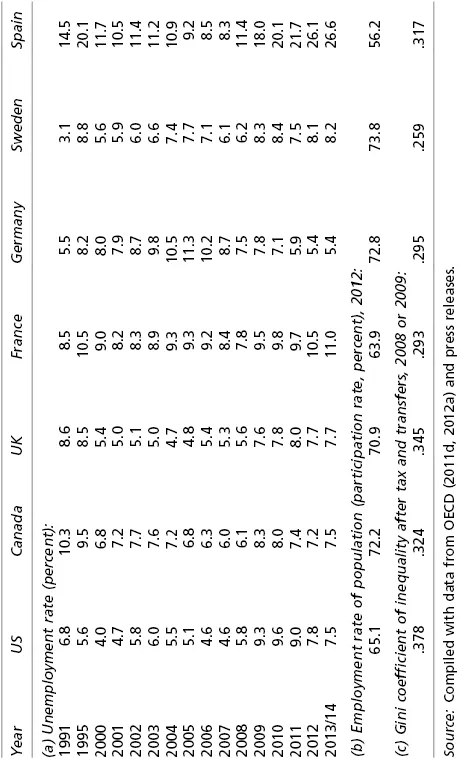

The OECD has devised a method to standardize or harmonize these two diverse methods of collecting unemployment data so that countries can be easily compared. Section (a) of table 1.1 shows some of these harmonized rates for a number of countries, and figure 1.1 graphs the US unemployment rate from 1950 to 2012. Clearly, the unemployment rate has increased since 2000. Figure 1.1 shows US unemployment rates going back to 1950 and up to 2012. The latest figures there match the previous post-World War II peak figures during the oil crises of 1973–4 and 1980–2, when a clear structural factor – OPEC raising the price of oil – increased unemployment. This brought about a massive government effort to support training and create jobs through the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act. Since then OPEC has largely disintegrated as a unified force raising gas prices (Carollo, 2011), but new structural forces involving global trade and offshoring have taken OPEC's place from 2000 to the present.

Table 1.1: Harmonized unemployment rates and inequality for seven countries, 1991–2013/14

There are three types of unemployment: frictional, cyclical, and structural. Frictional unemployment is short-term in the sense that employers and workers more or less cannot find each other in weeks or months. It presumes that there are no other barriers to employment other than the right employees getting to the job openings that already exist in firms. This is often addressed through the relationship of vacancy rates in firms and unemployment outside of them. Improving information in the economy through better job placement information is often seen as a solution to this problem.

Cyclical unemployment refers to jobs not being available because the economy is in a cyclical downturn that occurs with the generally expected business cycle. This is short-term unemployment of one to two years. Some say that as worker wage rates decline, employers will be more able to hire workers and more interested in doing so. This neo-classical economic theory ran into trouble during the great depression when the jobs took an inordinately long period of time to reappear. It was also accompanied by currency deflation, which exacerbated the problem. With employers engaging in repeated cuts to save money, the economy hit a downward spiral with more and more unemployment. In this sense, cyclical unemployment can become structural. Nonetheless, the post-World War II economy went through a number of business cycles that were somewhat temporary, and unemployment compensation generally tided workers over until the economic cycle reversed and jobs became more available. But in the last recession, this support has not lasted as long as the drought of jobs.

Evidence for Structural Unemployment

When Baily and Lawrence (2004) ask “what happened to the great US job machine?” they are not talking about a short-term blip. Structural unemployment indicates that there is something long-term and even permanent about the nature of unemployment. Jobs are not going to reappear, or they are not going to reappear for the specific unemployed people who are seeking them. Consequently, the duration of unemployment is long-term and workers cannot simply endure until the passing of temporary frictions or the recovery from the business cycle. This does not necessarily mean that unemployment lasts for decades, but it does mean that workers are unemployed and then enter into a process of accepting lower-level jobs, going on disability, or becoming homeless. Structural unemployment indicates that there is something else going on that alters the structure of the labor market, and that is what this book is about – the more enduring changes in the economy that make unemployment and declining social mobility a longer-term problem. And as part of these structures related to unemployment and labor markets, we will use an approach that indicates that there are different types of forces that structure economies through segmented labor markets that influence one's search for employment.

It is often difficult to differentiate between structural and cyclical unemployment. When unemployment first appears it is often labeled cyclical or due to a downturn in business, and when it hangs around, then the term structural unemployment may be used. There is no “label” that comes with unemployment so that one can differentiate these terms. If you ask someone who has lost their job if they are cyclically or structurally unemployed, they will just react with a puzzled look. Much debate goes on about this issue, but we point to five types of evidence that indicate that unemployment is structural: (1) long-term increases in unemployment for more than ten years, (2) the slowdown in the speed that jobs are filled, (3) the lengthening of the time spent in unemployment, (4) the declining participation rate in terms of people actually working, and (5) the increasing financial instability that makes cyclical crises more frequent than in the past.

First, economist J. Bradford DeLong, among others, argues that if unemployment “stays elevated for two or three more years” it “converts cyclical unemployment into structural unemployment” (2010a:1). While this does not pinpoint the actual structures of unemployment, persistently high and climbing unemployment rates above 5 percent over an extended period of time clearly lead to structural unemployment. If we look at Figure 1.1, we can see that from a trough in January 1970 to a peak in January of 1983 (13 years) unemployment rose to over 10 percent. Similarly, from the trough in January of 2000 to a near peak of January of 2013 (another 13-year period), unemployment rose to 10 percent. Each period clearly entailed structural unemployment, using DeLong's definition.

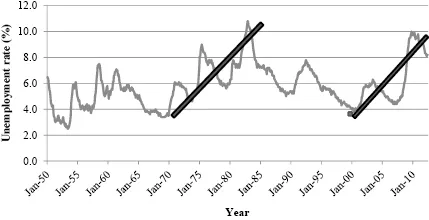

Second, the Beveridge curve measures the relationship of job openings to unemployment over time. Generally, one would expect that the more the job openings or vacancies, the lower the unemployment rate. Hence, the curve with vacancies on the vertical axis and unemployment on the horizontal axis should show a downward slope. Figure 1.2 shows a Beveridge curve from 2001 to 2013. Generally, the curve is relatively straight, but for the most recent period it has shifted to a more sluggish relationship between job vacancies and unemployment. In other words, the jobs are there but people are still unemployed. This shift to more joblessness for the most recent points suggests that the curve has moved to a higher level where unemployment persists even though there are more job openings. This is direct evidence...