- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

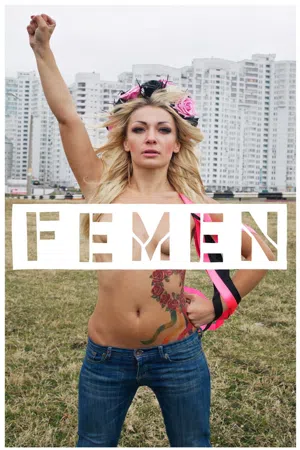

Femen

About this book

'Ukraine is not a brothel!' This was the first cry of rage uttered by Femen during Euro 2012.

Bare-breasted and crowned with flowers, perched on their high heels, Femen transform their bodies into instruments of political expression through slogans and drawings flaunted on their skin. Humour, drama, courage and shock tactics are their weapons.

Since 2008, this 'gang of four' – Inna, Sasha, Oksana and Anna – has been developing a spectacular, radical, new feminism. First in Ukraine and then around the world, they are struggling to obtain better conditions for women, but they also fight poverty, discrimination, dictatorships and the dictates of religion. These women scale church steeples and climb into embassies, burst into television studios and invade polling stations. Some of them have served time in jail, been prosecuted for 'hooliganism' in their home country and are banned from living in other states. But thanks to extraordinary media coverage, the movement is gaining imitators and supporters in France, Germany, Brazil and elsewhere.

Inna, Sasha, Oksana and Anna have an extraordinary story and here they tell it in their own words, and at the same time express their hopes and ambitions for women throughout the world.

Bare-breasted and crowned with flowers, perched on their high heels, Femen transform their bodies into instruments of political expression through slogans and drawings flaunted on their skin. Humour, drama, courage and shock tactics are their weapons.

Since 2008, this 'gang of four' – Inna, Sasha, Oksana and Anna – has been developing a spectacular, radical, new feminism. First in Ukraine and then around the world, they are struggling to obtain better conditions for women, but they also fight poverty, discrimination, dictatorships and the dictates of religion. These women scale church steeples and climb into embassies, burst into television studios and invade polling stations. Some of them have served time in jail, been prosecuted for 'hooliganism' in their home country and are banned from living in other states. But thanks to extraordinary media coverage, the movement is gaining imitators and supporters in France, Germany, Brazil and elsewhere.

Inna, Sasha, Oksana and Anna have an extraordinary story and here they tell it in their own words, and at the same time express their hopes and ambitions for women throughout the world.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

THE GANG OF FOUR

We’re sometimes called the ‘gang of four’. ‘We’ are Inna Shevchenko, Sasha Shevchenko (it’s a very common name in Ukraine, we’re not related), Oksana Shachko and Anna Hutsol. And ever since we formed the core of Femen, we’ve been inseparable. Three of us, Anna, Oksana and Sasha, are from the same town in western Ukraine, Khmelnytskyi. There we started to study philosophy and to be politically active, before arriving in Kiev. As for Inna, she comes from the town of Kherson, near Odessa, and she joined the other three founding members of Femen in Kiev, to become the fourth ‘pillar’.

What was life like for each of us before Femen? In what families did we grow up? Why did we feel the need to fight for women’s rights? How did we become atheists in a post-communist Ukraine where religion is taking over in ever more important areas?

1

INNA, A QUIET HOOLIGAN

I was born in a ‘godforsaken hole’ in southern Ukraine, in other words in a small provincial town, Kherson. They speak Russian there, like in Odessa, which isn’t very far away. It’s still a very Soviet town, where the USSR still seems to be in existence and nothing ever changes. It was in this quiet town, that’s infuriated me ever since my childhood, that I very soon started to tell myself I’d make a life for myself elsewhere.

When I was a little girl my only friends were boys, and I loved climbing trees. I dressed in shorts and sneakers; I hated dresses. This made Mom furious: she really didn’t like the fact I wasn’t like a model little girl. I didn’t even refuse to wear dresses, but Mom just knew I’d immediately get them dirty and tear them, either by climbing an oak tree or playing with stones on a construction site. Near our apartment block, there was one such site and in the evening, when the workers left, our little gang invaded it and built castles out of the bricks. I needed freedom, and instead of playing with dolls or messing about in a sandbox, I preferred to join the boys on more out-of-the-way expeditions. I didn’t want to be a boy, but I liked having them round me. I was a kind of quiet hooligan, who never took part in fights. The only person I quarrelled with from time to time was my older sister.

Apart from that, I was a well-behaved child. My parents never gave me a spanking. In fact, I’m lucky to have a very nice family. I’d define my mother as an ‘ideal woman’ for Ukraine. She was a chef in a restaurant before becoming chef in a university cafeteria. She’s a typical Ukrainian woman who works full time but also keeps her house spotless, cooks, and takes care of her husband and children without losing her temper or, more precisely, without ever showing her emotions – a nice, quiet, positive and very pleasant woman. But she’s not a fulfilled woman, even if she doesn’t complain about anything. She bears her fate, like a donkey carries its load, without realizing she could have had a different life. I suffered for her. In those days, I didn’t know the word ‘feminism’, but I thought this life was unfair. And the fact it was the norm was no consolation to me. I realized early on that I never would live like her. On the other hand, my sister, who’s five years older than me, completely internalized this model. In fact, she married at nineteen, had a child at twenty-one, and lives and works in Kherson. However, we’ve remained very close, and she’s always supported me.

Dad is a very emotional man, sometimes short-tempered, but he has a good heart too. In the family, we never had any real arguments. With his sense of humour, my father’s always turned any conflict into a mere joke. Our parents argued with my sister and me, without it ever turning nasty.

Dad’s a retired soldier, a former major in the troops of the Ministry of the Interior. I’ll never be able to imagine him without his uniform. During our childhood, when our parents went out, my sister and I would take turns to dress up in Dad’s uniform, but we never had any desire to try on Mom’s dresses or high heels. And when he got promoted, we’d make a hole in his epaulette to screw in a new star. For us, it was a sacred ritual!

If I got good grades in school and worked hard, this was also thanks to my father. He always talked to me as if I was a grown-up and kept telling me I was studying for myself, for my future. When I started at primary school, he told me that my adult life was about to begin. I quickly realized that there was a hierarchy at school: some children are better liked by the teachers, who straightaway help them and stimulate them. It’s a virtuous circle: if you work hard, you’re appreciated by the teachers, and they push you to develop your abilities and become even better. From the first year, I wanted to be the class representative. And I conducted the first electoral campaign of my life. I was elected by a show of hands. In fact, the role gave me a serious responsibility because it meant keeping a register of late arrivals and absences, organizing and lining up the pupils for outings and so on. I held this position throughout my time at school, up until my final exams.

Around the age of twelve, I went through a bit of a crisis. I suddenly realized that the boys preferred girls with dresses and pretty little shoes. As I wanted to be first in everything, I started to dress in a more feminine way and I grew my hair down to my waist. The effect was instantaneous: a lot of boys fell in love with me, including some of my friends. There were plenty of girls who wanted to be my friend because I was the leader of the class, but I thought they were airheaded chatterboxes and I kept my distance. I’d just one girlfriend who was also an excellent pupil. We shared the same table and with her I felt comfortable. In my class, out of twenty-two pupils, there were only seven boys. With my one girlfriend and these boys, we formed a separate group, away from the other girls.

When I was about fourteen, I developed a new ambition: I got it into my head that I’d become president of the school. For us, this was an important function, much more than being just class representative. The school president attends school board meetings and voices the wishes and grievances of the pupils. He or she also organizes competitions and festivals – an important personage, in short. And then the title itself is rather flashy: president! In theory, you can take on this post when you’re in the fifth year of secondary school but, in general, pupils vote for people who are in their final year. So my chances of being elected in the fifth year were almost zero. Still, I decided to stand against the nine other candidates. We campaigned for three weeks. We handed out leaflets and each made two public presentations of our platforms. These presentations took place in the main hall where candidates had to go on stage and try to convince the audience. Almost all the pupils took part in the elections, we all wanted to play at democracy, that game for adults. In each class there were ballot papers and boxes. The count was conducted by teachers and pupils drawn by lot.

The day after the election, our class was on duty to maintain order in the school. As class representative, I had specific obligations: I had to place pupils at monitoring stations in the canteen, the schoolyard and so on. Just then, the headmistress ran up and whispered in my ear that I’d won. It turned out that I’d won the majority of votes in thirteen classes out of fifteen – it was an outright victory! That was how my career as president started, and I was re-elected twice, in the last two years at school. This was my first ‘political’ experience, an unforgettable one, the start of which coincided with the 2004 presidential campaign.

The two main presidential candidates in Ukraine were Viktor Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych, who was backed by the outgoing President, Leonid Kuchma. Back in Kherson, everyone supported Yanukovych, both my family at home and the teachers at school. And then pressure was put on us too. For example, Mom told us that, at her workplace, officials in the local government had threatened to fire anyone who voted for Yushchenko. I tried to explain to my mother that this was bollocks, but she was scared. In eastern Ukraine, most people were aware that Yanukovych wasn’t a good candidate, but, out of fear of retaliation or indifference, many were ready to vote for him in spite of everything.

I remember propagandists from the Donbas, the stronghold of Yanukovych, claiming, ‘He’s a local lad, he went to prison, like so many other people, for snatching hats.’1 This kind of activity is usually carried out by small-time thugs who snatch the hats off people’s heads and only give them back if they’re given a few coins in exchange. That said, metaphorically speaking, this is how the majority of Ukrainians live – committing petty crimes to survive when they’re living in poverty. So it was a clever propaganda technique to present Yanukovych as a man of the people challenging the intellectual Yushchenko, the candidate of the Ukrainian-speaking elite and married to an American. The Yushchenko couple also spoke Ukrainian at home, and their children wore traditional costumes, shirts with embroidered collars, which was both incredible and intolerable for people in eastern and southern Ukraine. Indeed, the Soviet propaganda that supported Yanukovych presented Ukrainian nationalism as a kind of backwardness. To have a career, you absolutely had to be Russian-speaking.

At the same time, people wanted change, and all Yanukovych could offer was a continuation of the crooked Kuchma regime. A new man, a new background, a new face, but the same words, whereas the ‘extra-terrestrial’ Yushchenko had something really original and interesting to say. He called on Ukraine to foster links with Europe and the West and to escape from the Russian yoke, and his appeals carried home. Then there was the story about Yushchenko being poisoned with dioxin during the campaign – we still don’t know who was behind it: it led to a wave of sympathy for him. The election campaign was very eventful. Even though I was too young to vote, I understood that Yanukovych could represent neither the interests of the country nor mine. For me, this former petty criminal who ‘snatched hats’ and couldn’t even express himself correctly in his native language, Russian, let alone Ukrainian, was shameful. As president of the school, I attended the educational committee meeting at which the headmistress, who liked me and thought highly of me, openly called on the teachers to vote for Yanukovych. I didn’t have the right to protest at the meeting, but the next day I launched into my act. I braided my hair and arranged the braid around my head to look like Tymoshenko, Yushchenko’s main ally. I turned up at school with my hair like that, with an orange ribbon tied to my briefcase. Seeing me, my main teacher took me outside and forced me to undo my braid. She confiscated my orange ribbon and told me school wasn’t a place for politics. I then asked why the headmistress was openly getting involved in politics, but the teacher, who was actually very fond of me, just asked me to keep quiet. I was really shocked.

I was even more gutted when the official results of the election were announced: Yanukovych was declared the winner. This announcement provoked a revolt in Kiev and also in the provinces, known as the ‘Orange Revolution’. This was an idealistic period in the history of independent Ukraine. It was also at this time that I learned about political activism. Everyone was talking about democracy, on television and in the streets. It was a new buzzword, especially in my region. Hundreds of thousands of protesters stood fast in the cold weather of December 2004. They camped for nearly two months out on the central square in Kiev, known as the Maidan. Even in the little, apolitical towns such as Kherson, people who had never been interested in politics took part in fights between ‘Orange’ supporters and the ‘Blues’ who were on the side of Yanukovych. That was the most important thing: for a few months, people ceased to be indifferent. Too bad this revolution turned sour later, despite Yushchenko’s victory, achieved in the third round under pressure from protesters.

After these few tumultuous months, I returned to my studies. The general level of education was awful but we still learned English better than the average students in Ukraine. By now, my hopes were pinned on winning the gold medal at the end of my studies. I badly wanted a medal, but it didn’t work out that way. To win a medal in the provinces, where the quota was very limited, you needed to get high marks not only in your last year at school, as in Kiev, but also in the two previous years. Unfortunately, I’d got one ‘good’, instead of a ‘very good’ mark a couple of years back, and that was enough to put me out of the running. I couldn’t stop crying!

Despite not winning this medal, which would have helped me gain admission to college, I decided to try for a place on the journalism course at the best university in the country, the National University of Kiev, named after the great Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko. Mom tried to change my mind by suggesting I should stay in Kherson, where there’s also a university. To her way of thinking, it was absurd to want to go to Kiev when my home and my parents were in Kherson. I couldn’t understand her logic: how could she not want the best for her child?

I left for Kiev with Dad. I took seven exams in a month. The day after each examination, at 7 a.m., I ran into college to look at the lists and see whether I’d been eliminated or not. It was a really horrible few days … Finally, I won a place in spite of the competition – there were five of us after each place – but I had to pay. In Ukraine, there are very few free places for higher education, and in practice they’re reserved for children of MPs and politicians. For an ordinary person, it’s simply impossible to benefit from free education, even if you’re a genius from a very poor family.

The first day in college, I felt like … a little girl from the provinces. Almost all the other students came from Kiev, from wealthy families. They’d already toured round half of the planet, while I was still just discovering the capital city of my own country. I was ashamed to show how little I knew of what they were talking about. I was so aghast that I even wondered if coming to this prestigious location hadn’t been a terrible mistake. However, I immediately started thinking up ways to impose my leadership because I couldn’t see myself otherwise than as a leader. It wasn’t easy, but one month later I was elected head of my study group, and in the same year I was elected president of the parliament of university students.

At Shevchenko University, they elect a parliament composed of students from all faculties, then this parliament elects its own president. So my role was to represent the students vis-à-vis the rector and the professors, to convey their demands and to inform the staff of students’ problems. For me, this was an excellent school for political struggle. The young people in the students’ parliament are often the children of real deputies – the younger generation intent on going into politics. There were some really interesting people among them, and several of these became friends of mine.

That said, my daily life wasn’t easy. I lived in the students’ residence, which was a long way from the main building of the university. The parliament sessions took place every Wednesday between 8 p.m. and 11 p.m., and I went home around 1 a.m., which was very difficult in winter when it’s dark and the temperature drops well below zero. Mom kept moaning on the phone: ‘What’s the point of it all?’

I was alone in Kiev, without any family. Yet I started to love this great, bustling city and I didn’t suffer from loneliness. In my second year, I was contacted by the city administration. One of them had seen me in the student parliament and was favourably impressed. During the interview at the city hall, they told me: ‘You’re a promising journalist, come and work with us.’ I was thrilled – it was a prestigious job, a real dream for a budding journalist like me.

So I started working for the press service of the Kiev city hall, and my first thrilled response quickly evaporated. In fact, I cried every night, realizing that I’d over-romanticized the world of journalism. Each morning they assigned me my task for the day: I’d have to churn out a report on the mayor or one of his assistants who’d solved a particular difficulty, to the great satisfaction of his fellow citizens. The problem was that I knew full well these were lies, but I had to comply. My reports appeared in various Kiev newspapers, with different bylines. The newspapers were paid by the city administration for all these publications, of course.

All this happened in 2009, while Yushchenko was president. That’s why I say the Orange Revolution quickly turned sour. In actual fact, the ruling elites, and especially the big capitalists behind them, never changed. It was the same people, those who’d taken the reins of power when Ukraine became independent in 1991, who still retained control of the country. They simply changed their look: now they wear Brioni suits instead of raspberry-coloured jackets, like the Mafia at the start of the post-Soviet era. But they’re essentially the same: they still have the same way of thinking and the same dishonesty, and in addition they’re stupid. Their strength is that they gang up and support each other. Even in his supposedly democratic entourage, Yushchenko was a rare bird, an idealist. At least I hope so, because I still have illusions about him. He’s a man of integrity who managed to leave power in 2010 while still preserving his dignity, but he wasn’t a good politician and failed to reform the system.

In fact, I now realize that even when I was still a child, I was looking for a purpose. At school and in my first year at college, I dreamed of becoming a politician and sitting in a real parliament, not in a school or student parliament. My life changed when I met the trio of Femen: Anna, Oksana and Sasha. It was winter, late 2008 or early 2009. I corresponded with Sasha Shevchenko on Facebook, with no particular aim in mind, just: ‘Hi! Your name’s Shevchenko? So’s mine.’ We arranged to meet up in McDonald’s, and she suggested I should meet ‘the girls’, without giving further details. They used to get together in the Ban’ka cafe,2 located in a Turkish bath dating from the Soviet era. It was a rather dirty place, with typically Soviet tiles. I felt like I was back in Kherson. At the cafe, there was a long table and thirty or so girls sitting round it. They were planning an action against prostitution. That’s where I heard the name ‘Femen’ for the first time. At first I was all at sea. I didn’t really warm to them to start with – I didn’t know what feminism was all about. I had the weird idea that feminists were women with shaved heads, who wanted to look like men and wore men’s clothing. In short, ugly women who didn’t get laid enough. But right from the start, I liked their energy – the readiness for action that I’d always been looking for.

2

ANNA, THE INSTIGATOR

My family is Ukrainian. As my name, Hutsol, indicates, my father is of Hutsul origin. This small ethnic group of mountain-dwellers live in the Carpathians and speak a specific dialect of Ukrainian: they’ve been immortalized in Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, the film by Sergei Parajanov. However, my father’s family preserved nothing of this legacy – they moved to the Khmelnytskyi region, in western Ukraine, a ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Plates

- Manifesto

- A Movement of Free Women: Preface by Galia Ackerman

- Part I: The Gang of Four

- Part II: Action

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Femen by Galia Ackerman, Andrew Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Feminism & Feminist Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.