- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

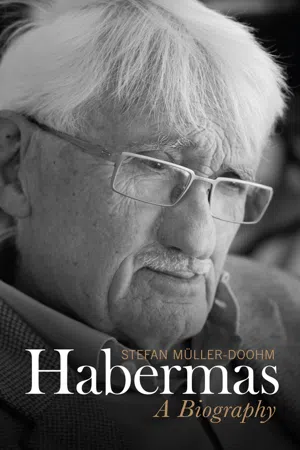

'Jürgen Habermas', wrote the American philosopher Ronald Dworkin on the occasion of the great European thinker's eightieth birthday, 'is not only the world's most famous living philosopher. Even his fame is famous.' Now, after many years of intensive research and in-depth conversations with contemporaries, colleagues and Habermas himself, Stefan Müller-Doohm presents the first comprehensive biography of one of the most important public intellectuals of our time. From his political and philosophical awakening in West Germany to the formative relationships with Adorno and Horkheimer, Müller-Doohm masterfully traces the major forces that shaped Habermas's intellectual development. He shows how Habermas's life and work were conditioned by the possibilities offered to his generation in the unique circumstances of regained freedom that characterized postwar Germany. And yet Habermas's career is fascinating precisely because it amounts to more than a corpus of scholarly work, however original and influential that may be. For here is someone who continually left the protective space of the university in order to assume the role of a participant in controversial public debates Ð from the significance of the Holocaust to the future of Europe Ð and in this way sought to influence the development of social and political life in an arena much broader than the academy. The significance and virtuosity of Habermas's many writings over the years are also fully and expertly documented, ranging from his early work on the public sphere to his more recent writings on communicative action, cosmopolitanism and the postnational condition. What emerges from this biography is a vivid portrait of one of the great public intellectuals of our time Ð a unique thinker who has made an immense and lasting philosophical contribution but who, when he perceives that society is not living up to its potential for creating free and just conditions for all, becomes one of its most rigorous and persistent critics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

Catastrophe and Emancipation

The moment of catastrophe is also the moment of emancipation.1

1

Disaster Years as Normality: Childhood and Youth in Gummersbach

Our life-form is connected to the life-form of our parents and grandparents through a mesh of familial, geographical, political, and also intellectual traditions which is difficult to disentangle – through an historical atmosphere, that is, which made us what and who we are today.1

Nineteen hundred and twenty-nine. Jürgen Habermas was born on 18 June 1929 in Düsseldorf, on the Rhine, the second of three children. It was a beautiful summer that year – the same year that Thomas Mann received the Nobel Prize for Literature and Erich Maria Remarque’s anti-war novel All Quiet on the Western Front became a bestseller – but it was also a time shaken by economic crises and by attempts, from both the left and the right, to destabilize the Weimar Republic, whose imminent demise was slowly becoming apparent. Since the spring of that year, it had been clear that an economic depression could no longer be avoided. The year 1929 would go down in history as the beginning of the worldwide Great Depression. After the heroic times of the arts had long faded, the ‘Golden Twenties’ came to an end and real wages, which had up until that point been comparatively high, began to fall. People still danced the Charleston and the ladies’ skirts still became shorter and shorter; from January, the picture houses showed Ich küsse Ihre Hand, Madame [I kiss your hand, Madame] – one of the last silent films, which, however, contained a single song. The film starred Marlene Dietrich in the female lead role, and the tango song, released the previous year and sung by Richard Tauber, became a hit, selling half a million copies.* In Munich, performances by Josephine Baker were banned because clerical circles feared for public decency, while in Berlin the newspapers reported acts of censorship by magistrates aiming to prevent scandals at the Theater am Schiffbauerdamm. What could not be prevented were the gunfights between National Socialists and communists that broke out in the Reich’s capital. These street battles were the tip of the iceberg, indicating growing political and ideological tensions.

Thus, for instance, monarchists fought against republicans, conservatives against liberals and social democrats, völkisch nationalists against proponents of a state based on citizenship [Staatsbürgergesellschaft], anti-Semites against the advocates of a continuing social integration of Jewish Germans, those who glorified war against those who were sceptical towards war, mystagogues of the Reich against political realists, those who defended the thesis of a German ‘Sonderweg’* against self-critical pragmatists, religious socialists against orthodox Lutherans, prophetic dreamers against supporters of routine politics, geopolitical dogmatists against clear-headed representatives of particular interests, those who sympathized with Italian fascism against the defenders of the republic, advocates of the total state against liberal democrats – it was a true witches’ cauldron of political theories and phobias in which very categorical and often fundamentalist oppositions always set the tone.2

The death of the liberal-conservative politician Gustav Stresemann in October 1929 would lead to fatal consequences for sensible German foreign policy. In him, the country lost its most important representative – someone who had aimed to balance interests and to achieve understanding with other nations. He had, for instance, offered German support for Aristide Briand’s extraordinary suggestion at the League of Nations to create a ‘United Nations of Europe’.

The unemployment figures rose month on month during that year and passed the 8 million mark. On 24 October 1929, the New York Stock Exchange crashed, triggering a worldwide economic crisis: the Great Depression had begun. As a consequence, the National Socialists were able to raise their share of the vote in state elections significantly. Their propaganda was directed predominantly against the result of the negotiations in June over the conditions of Germany’s payment of reparations following its defeat in the Great War, despite the fact that the so-called Young Plan actually meant a reduction of the annual burden and allowed Germany to pursue independent financial policies again.

A coalition cabinet of five major parties headed by the social democrat Heinrich Brüning governed this republic that lacked republicans and whose president was, in 1925, an aged Generalfeldmarschall who was himself an opponent of republicanism. The government’s obvious weakness in leadership meant that the very party fundamentally opposed to the Weimar Republic succeeded in becoming a mass movement. The ‘Sturmabteilung’ was expanded into an effective terror organization and the Nazi Party set about creating its own media company from scratch. Gradually, the National Socialists began to dominate public debate on all sorts of topics, developed new initiatives for ‘self-help’ to combat unemployment, and started aggressively propagating the almost messianic image of the ‘Führer’.3

This mixture of cultural sensations and politically explosive, economically catastrophic events would certainly have been observed by the people of Gummersbach, a small town with a population of 18,000 in the Oberbergisches Land, set in the Prussian part of the Rhine area. This was the home of the family of Grete and Ernst Habermas. Perhaps later, when growing up, the boy would have been told about the important events that took place in the year he was born, a year in which there was certainly more shadow than light. The Gummersbach Habermas would remember as an adult was a place which, after the Gründerzeit* and the turn of the century, had been transformed into an ‘urban community’ and an ‘industrial city’.

The route to the Gries butcher’s shop passed the Gasthof Winter, the Café Garnefeld and the Wetzlars’ house; and, on the way to my piano lessons in Winterbecke, I saw the Hotel Koester and the old Magistrate’s Court once a week. … From my youth I remember more strongly the electric tramway …, the indoor swimming pool, the town hall, the Schützenburg, the community hall, and Schramm’s toy shop.4

Worth mentioning too is the Vogteihaus† in the centre of the city, known as ‘Die Burg’, as well as the Oberbergisches Land cathedral, which was built in the eleventh century in Romanesque style as a hall church, and the many dams in the densely wooded area of the Oberbergischer Kreis.

In his childhood, the world of Karl May took a hold of the imagination of the adolescent boy, who confesses that for a long time he was egocentric and preoccupied with his own psychological problems.5 As a pupil, he found plenty of books to read in the family library, among them the novellas and novels of Gottfried Keller and Conrad Ferdinand Meyer. Later, he would read Ernst Jünger’s Copse 125 and his diary The Adventurous Heart. The Björndal trilogy by the Swedish author Trygve Gulbranssen and the novels and plays by Selma Lagerlöf and Knut Hamsun also formed part of Habermas’s literary education.

The Protestant family in which Habermas grew up was the product of petit bourgeois elements from his mother’s side and a lineage of civil servants from his father’s, who had climbed up the social ladder.

The name Habermas first appears in documents from Western Thuringia in the second half of the century of the Reformation: around 1570, Hanns Habermas was given the rights of a citizen in Treffurt, a place north of Eisenach. From then on, there were several generations of Habermases who lived in the residential city as well-respected master cobblers.

The family. Ernst Habermas (1891–1972), the son of a parson, who was later director of the teachers’ seminary, and a large-scale farmer’s daughter, first entered the teaching profession at grammar school level at the Oberrealschule* in Gummersbach.6 He gave up his first profession for financial reasons in 1923, shortly before his wedding, in order to become the representative of the local branch of the Bergische Industrie- und Handelskammer (IHK) [Chamber of Industry and Commerce]. Already politically active in an association, he studied, alongside his job, at Cologne University, where he was awarded the title of Doktor der Wirtschaftlichen Staatswissenschaft [Doctor of economic state science] for a thesis entitled ‘Die Entwicklung der oberbergi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Illustration Acknowledgements

- Prologue: The Other among his Peers

- PART I CATASTROPHE AND EMANCIPATION

- PART II POLITICS AND CRITIQUE

- PART III SCIENCE AND COMMITMENT

- PART IV COSMOPOLITAN SOCIETY AND JUSTICE

- Epilogue: The Inner Compass

- Genealogy

- Chronology

- List of Habermas’s Lectures and Seminars

- Visiting Professorships

- List of Archives

- Bibliography of Works by Jürgen Habermas

- Secondary Literature

- Index

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Habermas by Stefan Müller-Doohm in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Philosophy & Modern Philosophy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.