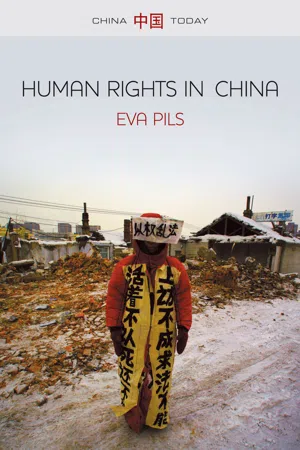

In the 2010 documentary film Emergency Shelter, a group of friends gather in a park in downtown Beijing. The friends are there to support a couple temporarily rendered homeless by a long-term fight with local authorities against the demolition of their house. Seated on park benches around the wheelchair-bound rights defender Ni Yulan and her husband, the small group chat about their own experience of petitioning and complaining against the authorities. Their conversation reflects the presence of history in contemporary Chinese discourses about law, rights and justice: the words people use, the ideas they draw on, some of the assumptions they make. Zhang Aixiang, a middle-aged woman who has brought her friends clothes and food, thinks that the officials of the legal system are all in collusion, and that this is why the authorities fail to handle complaints properly.

Wang Guihua, who points out that she has some teeth missing from an encounter with the authorities, says,

And Ye Guozhu cites the proverb, ‘No injustice (yuan) without perpetrator, no debt without creditor.’4 Clearly he thinks that corrupt and undutiful officials will get what was coming to them one day.

We do not learn much about the individual stories behind their comments, and we do not get to hear the government's argument in their respective cases. Only Ni's and her husband's story is told in some greater detail in the film: old Beijing residents, they lost their home along with thousands of others in the great construction wave in the early 2000s; and Ni – disabled as a result of earlier police brutality, she explains – was sent to prison for her attempts to advocate on behalf of their own and other families. At the time of the film, she has just been released, and she and her husband are camping out not far from where their home once stood. Focusing away from this individual story, the conversation with their friends shows how her experience is mirrored in theirs. We are given a glimpse of the way citizens are complaining to and reasoning with the government, and see them explaining their situation to the invisible videographer, and to us. They are deeply critical, for example when Zhang Aixiang comments on the official jargon of ‘social stability maintenance’ that is typically used to justify coercive measures against petitioners like herself:5

They are also sceptical about getting anywhere with their complaints, but nevertheless defiant: one can sense that, regardless of how difficult it may be, they are not going to give up easily. They have a sense of their own power: they know that even if they won't get justice (whatever this might mean) they can at least make life difficult for the officials supposed to deal with them and keep them in check. In Havel's phrase, one might call it a form of ‘power of the powerless’.7 It is a power connected to people's experience of injustice and their willingness to seek justice.

Through the individual chapters that follow, human rights and related ideas are interpreted and reinterpreted across a variety of national, cultural and political boundaries,8 and it is shown how deeply contentious they are: not only (for reasons discussed in chapter 2) and not even primarily in the courts, but also in the streets and on the internet, in books and bars, in lecture halls and on social media. Of course, one might say, views gathered in these venues are individual. For example, the above brief comments and attitudes of Zhang, Wang and Ye do not tell us much about the thoughts, expectations and aspirations of the 1.4 billion Chinese people as a whole. Taking stock of these as a whole would be a giant undertaking – and it would not be very helpful in any case, since all we would discover is that people in China, like elsewhere, disagree about big abstract ideas such as rights, wrongs and justice; and that what they say is not always coherent. Assessing what rights people hold as human rights, whether or how these are – or are not – protected, and how they are discussed and asserted and used in contentions between citizens and the state requires moral and legal judgment, according to the view adopted here. It cannot be limited to describing others' views, but needs to engage critically with the views and practices it describes, working through them towards a normative assessment.9 To do so, it is particularly important to examine the views and attitudes of those who, like the three speakers above, experience human rights violations, those who are involved in addressing them, as well as those who perpetrate or justify violations – often, but not always, government officials.

The purpose of the following sections of this chapter is to give a sense of the most important disagreements and debates affecting human rights in China, understood as an interpretive social practice. It sets out what one might usefully call the justice and governance traditions of China: the conceptions and practices related to justice reflected in its political and institutional history, as well as in its vast philosophical and literary heritage. These traditions remain present in contemporary official and public discourse about rights. Subsequent chapters will address some aspects of the legal-political system, some basic substantive rights or groups of rights, and wider social practices related to rights assertion.10 The picture that emerges is rich and colourful, as well as full of tensions. There are great differences not only in pre-PRC Chinese engagement with the concept of justice, but also within the history of the PRC, from the totalitarian years under Mao Zedong to the ‘post-Mao reform’ and what one might call the current ‘post-reform’ era. All of this history informs how justice-based claims and complaints about injustice are articulated and dealt with today. There are continuities, as well as tensions, ruptures and contradictions.

Three themes are particularly important. First, there is the tradition of bringing grievances and the closely related concept of yuan, ‘wrong’ or ‘injustice’. It centres in the belief that the wrongs suffered by any individual person must be addressed and righted. Second, there is the concept of rights, part of a liberal conception of law and justice, which began to be articulated and debated in China from the nineteenth century onwards. By now, human rights have become part of the justice traditions of China. Lastly, there are what I will call human rights counterdiscourses: an assemblage of influential ideas and arguments, practices and institutions that propagate a vision of order in which human rights would have no place or, at best, a very diminished function, even though the language of human rights might still be used when convenient: a politically authoritarian order claimed to be more appropriate for China. Those who propagate these countervisions of order sometimes use morally relativist arguments; but far from upholding a distinctly traditional, Chinese conception of justice (as moral relativism might suggest), they suppress the more indigenous yuan discourse when convenient. These counterdiscourses explain, in part at least, why human rights in China remains so fiercely contested a practice. As they are propagated beyond China's territorial borders, they play a ...