- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

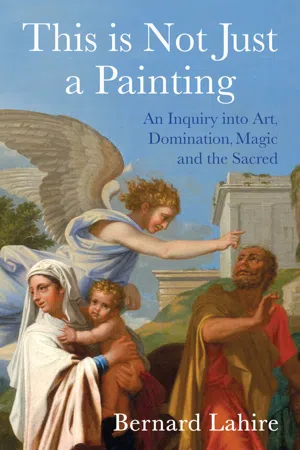

This is Not Just a Painting

About this book

In 2008, the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon acquired a painting called The Flight into Egypt which was attributed to the French artist Nicolas Poussin. Thought to have been painted in 1657, the painting had gone missing for more than three centuries. Several versions were rediscovered in the 1980s and one was passed from hand to hand, from a family who had no idea of its value to gallery owners and eventually to the museum. A painting that had been sold as a decorative object in 1986 for around 12, 000 euros was acquired two decades later by the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon for 17 million euros. What does this remarkable story tell us about the nature of art and the way that it is valued? How is it that what seemed to be just an ordinary canvas could be transformed into a masterpiece, that a decorative object could become a national treasure? This is a story permeated by social magicthe social alchemy that transforms lead into gold, the ordinary into the extraordinary, the profane into the sacred. Focusing on this extraordinary case, Bernard Lahire lays bare the beliefs and social processes that underpin the creation of a masterpiece. Like a detective piecing together the clues in an unsolved mystery he carefully reconstructs the steps that led from the same material object being treated as a copy of insignificant value to being endowed with the status of a highly-prized painting commanding a record-breaking price. He thereby shows that a painting is never just a painting, and is always more than a piece of stretched canvass to which brush strokes of paint have been applied: this object, and the value we attach to it, is also the product of a complex array of social processes– with its distinctive institutions and experts– that lies behind it. And through the history of this painting, Lahire uncovers some of the fundamental structures of our social world. For the social magic that can transform a painting from a simple copy into a masterpiece is similar to the social magic that is present throughout our societies, in economics and politics as much as art and religion, a magic that results from the spell cast by power on those who tacitly recognize its authority. By following the trail of a single work of art, Lahire interrogates the foundations on which our perceptions of value and our belief in institutions rest and exposes the forms of domination which lie hidden behind our admiration of works of art.

Information

Book 1

History, domination and social magic

Not much attention has been paid to the retreat of sociologists into the present. This retreat, their flight from the past, became the dominant trend in the development of sociology after the Second World War and, like this development itself, was essentially un-planned. That it was a retreat can become clearly visible if one considers that many of the earliest sociologists sought to illuminate problems of human societies; including those of our time, with the help of a wide knowledge of their own societies’ past and of earlier phases of other societies. The approach of Marx and Weber to sociological problems can serve as an example.Norbert Elias, ‘The Retreat of Sociologists into the Present’, Theory, Culture and Society, 4 (2), June 1987, p. 223

1

Self-evident facts and foundations of beliefs

The past is not fugitive, it stays put. […] After hundreds and thousands of years, the scholar who has been studying the place-names and the customs of the inhabitants of some remote region may still extract from them some legend long anterior to Christianity, already unintelligible, if not actually forgotten, at the time of Herodotus, which in the name given to a rock, in a religious rite, still dwells in the midst of the present, like a denser emanation, immemorial and stable.Marcel Proust, In search of lost time. II. The Guermantes Way, London, Vintage, 2000, p. 482

This fixation of social activity, this consolidation of what we ourselves produce into an objective power above us, growing out of our control, thwarting our expectations, bringing to naught our calculations, is one of the chief factors in historical development up till now. The social power, i.e. the multiplied productive force, which arises through the cooperation of different individuals as it is determined by the division of labour, appears to these individuals, since their co-operation is not voluntary but has come about naturally, not as their own united power, but as an alien force existing outside them of the origin and goal of which they are ignorant, which they cannot thus control, which on the contrary passes through a peculiar series of phases and stages independent of the will and the action of man, nay even being the prime governor of these.11

At each stage there is found a material result: a sum of productive forces, an historically created relation of individuals to nature and to one another, which is handed down to each generation from its predecessor; a mass of productive forces, capital funds and conditions, which, on the one hand, is indeed modified by the new generation, but also on the other prescribes for it its condition of life and gives it a definite development, a special character. It shows that circumstances make men just as much as men make circumstances. This sum of productive forces, of capital funds and social forms of intercourse, which every individual and generation finds in existence as something given; is the real basis of what the philosophers have conceived as ‘substance’ and ‘essence of men’.12

Table of contents

- Cover

- Front Matter

- Acknowledgements

- Plates

- Introduction: unravelling a canvas

- Book 1. History, domination and social magic

- Book 2. Art, domination, sanctification

- Book 3. On Poussin and some Flights into Egypt

- Conclusions

- Post-scriptum: the conditions for scientific creation

- Summary of information sources consulted

- Bibliography

- Supplementary bibliography

- Index

- End User License Agreement

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app