![]()

1

CARTOGRAPHIES AND GEOGRAPHIES

1.1 INTRODUCTION

It is a salutary experience to begin by looking back at several texts widely used in courses on the UK’s human geography as recently as the early 1970s. Dury (1968) and Stamp and Beaver (1971) bore the imprint of geography’s determinist legacy in their inventories of physical resources and descriptions of the physical characteristics of places. Particularly noteworthy was their coverage of primary production and industrial patterns within a conventional framework of location theory. House (1973) and Chisholm and Manners (1971) took a rather different approach. Reflecting the spirit of the times, they displayed considerable faith in the capacity of various forms of planning. House (1973), for example, spoke optimistically of the scope for ‘more comprehensive regional planning’. He concluded with the statement that ‘the necessary further management of the UK space … will not be feasible without … greater and more decisive public intervention to channel market forces in the national interest’ (p.359). If the quotation ceased at ‘intervention’ we might regard this as ‘old Labour’ thinking, but the emphasis on working with the grain of market forces has a very contemporary ring.

These works were products of their times and should probably not be read through twenty-first-century lenses. Stamp and Beaver was in its seventh edition, having originally been published in the mid-1930s. Nevertheless several important lacunae should be noted. Almost totally absent was a consideration of political geographies: even that subdiscipline’s traditional concerns (electoral geography; subnational government) hardly feature. Nor is there explicit consideration of the role of the state except in a rather technocratic way rather than as a political entity. Social polarisation and poverty are hardly mentioned, notwithstanding the rediscovery of poverty in other disciplines during the early 1960s. Other planes of social division do not figure. There are some references to the uneven landscapes of welfare provision albeit at a regional scale (Coates and Rawstron, 1971). Apart from discussion of the imminent accession to the EC (in House, 1973) there is little sense of the UK’s place in a wider scheme of things while, despite concern about limits to growth, discussion of environmental issues receives little attention beyond resource inventories and consideration of how to maximise the supply of them.

These silences and exclusions reflect a discipline which was only beginning to engage with social issues and break out of its regionalist and determinist legacy. They also reflect what, with hindsight, appears as an era of steady growth, social harmony and rising prosperity, and political consensus. Neither of these sets of circumstances still apply; nor is there much industry to write about. Perhaps three contingent influences precipitated a dramatic change in the character of work on the UK’s human geography. First, there was the rising tide of radical ideas, drawn primarily from Marxist economic and political theory. Second, recessionary conditions in the early 1970s posed a challenge to conventional accounts of regional development. It became clear that explanations of the impacts of restructuring needed to go beyond narrow ‘location factors’ to consider the role places played in spatial divisions of labour. Third, the 1979 election result prompted a re-evaluation of the role of the state and, for some, symbolised a decisive break from an era of ‘one nation’ politics and its replacement by a divisive politics of inequality, with profound geographical consequences. Consequently, the widening of regional divisions in the UK during the 1980s, popularised in the notion of the ‘North-South divide’, was followed by a rash of texts on the human geography of the UK (Dickens, 1988; Ball et al. 1989; Hudson and Williams, 1995; Lewis and Townsend, 1989; Mohan, 1989; Balchin, 1990; Champion and Townsend, 1990; Cloke, 1992).

It is, of course, undeniable that the Conservative governments not only rewrote history but also reshaped geography, selectively reconstructing the map of regional inequality as part of a spatially selective ‘two nations’ project (see chapter 3). It was therefore an essential political and academic task that new academic geographies were developed to engage with the geopolitical bases and geographical consequences of the Thatcher administrations. But ultimately several stones were left unturned. Put crudely, some could be described as ‘cartographies of distress’ or as the ‘geographical consequences of Mrs Thatcher’. There were several demonstrations of the extent and character of regional inequality in the UK, often through rather broad-brush regional contrasts on a range of socio-economic indicators, with some disaggregation to the subregional level. There was a tendency to treat topics (deindustrialisation, reindustrialisation, housing, education, electoral geography, etc.) as discrete entities, rather than demonstrating the links between them. Such a cartography also requires a discussion of why, precisely, geography matters to the operation of society: of course there are variations in economic activity and levels of human welfare – there always have been – but are they anything other than cartographic curiosities? If not, then the authoritative evidence of inquiries such as the Rowntree Report (1995) has demonstrated the facts of socio-spatial inequality so convincingly that it is debatable what more can be contributed by geography.

Analysing spatial inequality clearly requires more than mapping a ‘two nations’ project. What this book attempts to do is shift attention from spatial patterns per se to analysing academic and political debates about these patterns. For example chapters 4 and 5 focus on how contemporary trends in the organisation of production are to be understood while chapter 6 addresses debates about flexibility in the labour market. Chapter 7 moves away from simply mapping incomes to considering the institutional influences on the distribution of money and finance. Other chapters are organised in similar ways.

The book also addresses the fact that regional and inter-regional divisions have not been abolished but have rather emerged in new forms. Questions of spatial separation and segregation have received increasing attention; for example, social policy is increasingly about the management of a spatially concentrated and marginalised segment of the population, which some would pejoratively describe as an ‘underclass’. The relationships between diverse social groups in an increasingly fragmented socio-economic landscape raise the question of whether support for a comprehensive welfare state can be maintained. Questions of territorial management have been thrown into sharp relief by the referendum campaigns in Scotland and Wales, the very different results of which reveal much about the differing bases of nationalist movements in the two countries (chapters 10 and 11). The pressures of globalisation have necessitated a reappraisal of the state’s conventional role in regional policy which appears set to re-emphasise the institutional capacities and resources of particular places (chapters 3 and 12). These are all grounds for saying that there is a need for a fresh discussion of the UK’s human geography. To frame the chapters which follow, then, there is first a discussion of the ways in which regional inequalities have been mapped. A consideration of myths of regional inequality indicates why these matters are of more than just cartographic significance, and a section on ‘realities’ attempts to put regional inequality into a comparative context. Discussion then moves to the geographies – the academic accounts of and explanations for the UK’s human geography, focusing principally on the changing economic landscape.

1.2 CARTOGRAPHIES: REPRESENTING REGIONAL INEQUALITY

Myths …

Regional inequalities have in a sense entered the realms of popular and literary mythology, in the form of stereotypical accounts of the character of places, and of their residents. Jewell (1994) demonstrates the longevity of such myths, showing that stereotyping of ‘Northerners’ as ‘ferocious, obstinate and unyielding’ is evident in the twelfth century. For this period there is much more evidence of what ‘Southerners’ thought than there is for their northern counterparts; Southerners, ‘from the more confident, dominant culture, were quick to categorise what they saw’ (p. 209) – an account which could clearly be given an Orientalist inflection. She attributes what were recognisable differences prior to industrialisation to different forms of agricultural organisation.

Much of the image of the ‘North’ derives from novels from the nineteenth-century onwards describing the sharp social and economic contrasts between London and the emerging industrial heartlands of the West Midlands and Lancashire. The novels and writings of Dickens, Disraeli, Orwell, Bennett and Sillitoe have forged an enduring image. Shields (1991, 210–11) shows how the ‘North’ is constructed as alien, if utilitarian: Dickens, in Hard times, for example, referred to ‘Coke-town’, widely believed to be based on Preston, Lancashire, as being a ‘town of unnatural red and black, like the painted face of a savage’, with chimneys belching ‘interminable serpents of smoke’. There was ‘nothing in this town but what was severely workful’ (quoted in Shields, 1991, 210). Such writings helped establish contrasts not just between places but between their inhabitants. Northerners came to be seen as warmhearted, generous, hardworking, dogged, collectivist, brusque and aggressive; Southerners as snobbish, soft and lazy, individualistic and living by brain rather than brawn. The North’s image of itself was as a place where wealth was made, while the South was where it was squandered (Pocock, 1979). Such literature has created influential images which have been difficult to break down.

Thus, following the re-emergence of concern about the ‘North-South’ divide in the 1980s, media coverage established stereotypes of ‘two nations’. Shields (1991) summarises much of the writing on this topic. The ‘North’ is never a precisely defined and mapped-out region with clear borders, but despite this, certain defining features can be discerned. Consider the following:

Britain is split by a North-South Divide running from Bristol to the Wash. The victims of decaying smokestack industry live in the North, the beneficiaries of new hightech finance, scientific and service industries, plus London’s cultural and political elite, are in the South. Cross the Divide, going north, and visibly the cars get fewer, the clothes shabbier, the people chattier.

(The Economist, 7 February 1987; capitalisation of ‘Divide’ in original!) (quoted in Shields, 1991, 232)

This reiterates the demarcation of the divide (the Severn to the Wash) and the package of images which make up the myth of the ‘North’. These include the industrial character of the region, the chattiness of its denizens, who live in the conditions of an earlier age untouched by technical progress and economic growth, and a general atmosphere of shabbiness. Although there were attempts to overcome such crude journalism, the effect was in general to reconfirm ‘the position of the North in the national discourse on the British regions even while providing evidence of its nonconformity to the stereotypes of that discourse’ (Shields, 1991, 240). Such evidence included demonstrations of affluence and depression (e.g. the presence of very wealthy areas in some northern cities) or reports which showed that not all talent and entrepreneurship was confined to the South, nor was the North devoid of places of interest. Yet the kind of anecdotes typically produced (successful football teams, regional shopping centres, museums or individual entrepreneurs) do not, individually or collectively, constitute a revival of the North.

As Taylor (1991a and 1993) demonstrates, such regional images also have their negative consequences. He describes the difficulties of persuading civil servants to move to the North East because of their perceptions about the culture of the region and of its remoteness; perceptions shaped, one presumes, largely by media and journalistic coverage. There is clearly much to do in order to shake off the image of the North as ‘an abnormal place to which one travelled in order to be bitten by the surroundings’ (Colls, 1992, 15). Conversely, such regional images and myths can form the basis of territorially based identities and, on occasion, political movements, while they can also be mobilised in defence of – or in order to promote the interests of – particular regions. Consider, for example, the role of regional images in promotional campaigns, such as the ‘Great North’ campaign mounted in the mid-1980s to help attract investment to the North East. The stress on the heritage of the region, its proud history of industrial innovation, and the salt-of-the-earth characteristics of its workforce – these characteristics were all used selectively to promote an image of a place amply deserving additional investment. Of course, such campaigns often rely in themselves on a highly partial history which typically erases class conflict and poverty (Sadler, 1993).

…And realities?

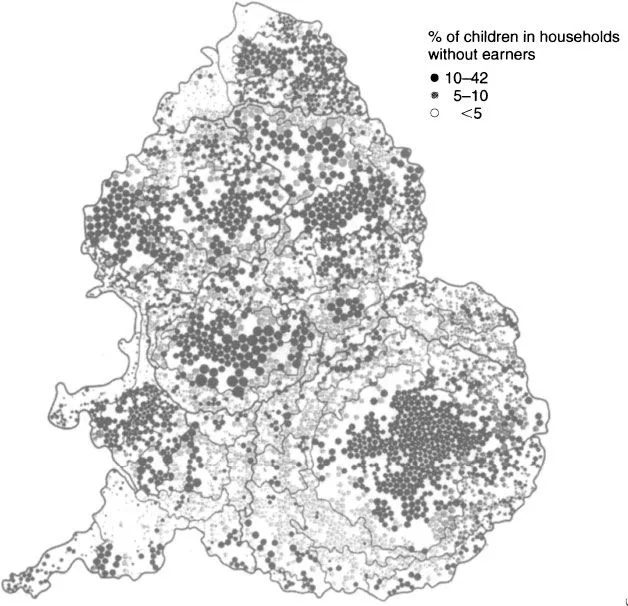

Is it possible to demonstrate, in any ‘objective’ or accurate way, the reality behind these myths? The endless procession of maps at the level of standard regions in academic texts certainly demonstrated the multifaceted nature of regional variation. Attempts at disaggregation of statistics naturally succeeded in showing the extent of within-region variation. These achieved a high level of sophistication in Dorling’s (1995) A new social atlas of Britain. He devised a cartogram in which it was possible to incorporate all electoral wards in the UK (approximately 10 000 in total) while maintaining their relative location. The consequence was, of course, massive distortion of the physical outline of the UK, but the benefit was a level of detail unmatched elsewhere. Moreover, the cartogram is scaled so that a constant area of map represents a constant unit of population. This focuses attention on areas where population is greatest and discounts peripheral rural areas with small populations. Figure 1.1 uses this technique to portray child poverty for electoral wards in England and Wales for 1991. The proxy variable used is the proportion of children living in a household where no adult was working at the time of the 1991 Census. Three types of ward are identified. In the richest third less than 5 per cent of children lived in households without earners. By contrast, in the poorest third of wards between 10 per cent and 42 per cent of children lived in households without earners. Attention is drawn immediately to the principal conurbations and former coalfields, where the cartographic technique used highlights wards with large populations.

Despite its technical sophistication, reliance on such quantitative indicators had its limitations. One response has been attempts to measure the more subjective dimensions of ‘quality of life’ (e.g. Rogerson, 1997). There are several reasons for this interest. Quality of life issues are held to be significant in underpinning migration decisions and processes, and in influencing the location decisions of private (and some public) organisations. Concern about simplistic and unreflexive use of economic indicators as one-dimensional measures of social development has also led to attempts to devise indicators of environmental quality. These debates are all tied in to the growing importance of environmentalism and to contemporary trends in social stratification – for example the ‘service class’ (see chapter 8) is said to attach considerable important to environmental quality. Drawing on national surveys which invited respondents to rank a number of attributes, the Quality of Life group produced weightings which were applied to measures drawn from published and unpublished sources (e.g. crime rates; house prices; leisure provision; scenic quality). The weighted measures were combined into one index of quality of life for 189 places. The contrasts between top and bottom on this index are revealing. The highest-ranking places are typically medium-sized towns in rural areas, with easy access to high-quality countryside and/or the sea, good educational and shopping facilities, and strong employment growth (e.g. Dumfries, Kendal, Hereford, Eastleigh) combined with historical attractions (York, Shrewsbury, Edinburgh). At the other end of the index, large cities are ranked badly (Hull, Nottingham, Bristol) as are a cluster of medium-sized towns in industrial parts of the Midlands and the North (Stockton, Wigan, Barnsley, Walsall, Mansfield). Interpreting these patterns is not easy, as the authors acknowledge; for example, there is some evidence of a preference for small towns but Edinburgh was ranked fourteenth despite being the fourth-largest city included in the study. These studies nevertheless provide endless ammunition for salvoes in place-marketing wars between local authorities competing for investment. More seriously they also reveal that, for those constrained to live in undesirable environments, a low quality of life can be a major source of stress and illness. Burrows and Rhodes’ (1998) study of unpopular places is a good example. They estimate that up to 25 per cent of residents in certain wards (dominated by public-sector estates) in many northern cities expressed high levels of dissatisfaction with their neighbourhood. This compares with less than 5 per cent at the other end of the spectrum.

FIGURE 1.1 Proportion of children in households without earners, England and Wales, 1991 (Dorling and Tomaney, 1995)

Thus far the spatial units used in the works referred to have all been based on geographical regionalisations – that is, each division of the country is self-contained and contiguous. Emphasising formal differences between places, based purely on geographical location, may conceal more fundamental functional differences. One way...