This is a test

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

A growing reliance on market disciplines and incentives characterised health care reform strategies in many countries in the 1990s, yet the country which relies most heavily on private health care - the U.S.A. - is the most expensive in the world and still fails to deliver affordable health care to millions of its citizens. This apparent paradox is the starting point for Markets and Health Care: A Comparative Analysis.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Markets and Health Care by Wendy Ranade in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Health Care Delivery. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

WENDY RANADE

This book starts with a paradox. Put crudely, in the study of health policy the United States has always been seen as a failure. While other Western democracies managed to combine a reasonably accessible and equitable system of health care for all their populations at an affordable cost to the nation, the United States - which alone of all the democracies still had a system based largely on private markets - combined the most expensive system in the world with millions of citizens uninsured or inadequately insured. As Moran puts it in Chapter 2, learning health policy lessons from the United States is rather like taking lessons in seamanship from the crew of the Titanic. Economic theory and practical experience seemed to combine to tell a forceful lesson: keep markets out of health care. Yet in the flurry of health care reform and restructuring that has characterised the 1990s the USA has gone from policy laggard to policy leader, the source of many of the ideas which underpin reforms elsewhere and in particular the introduction or strengthening of market principles in health care. The central point of our enquiry in this book is to try to answer the questions: why did this happen, and with what results?

A subtheme of the enquiry is the way in which policy learning and 'lesson drawing' between states takes place in an increasingly interdependent, information-rich world. Marmor (1995) observes that most policy debates in most countries are parochial affairs, rooted in national experience and developments, reflecting national political struggles and conflicting visions of the future. If (rarely) policy makers seriously look to foreign experience for solutions to problems it is used mainly as a tool of policy warfare in internal struggles, not policy understanding and careful lesson drawing. The international spread of promarket, pro-competitive ideas in health care reform has involved more than its fair share of myth-making, distortion and the selective use of evidence from other countries.

The book brings together an international group of health policy analysts with different disciplinary backgrounds: political science, health economics, public health and public management. Though each chapter reflects the disciplinary perspective of its author(s), the group benefited from a three-day colloquium held at the Longhirst campus of the University of Northumbria in Newcastle in July 1996 which enabled early drafts to be thoroughly debated and exposed to different disciplinary foci. Michael Hill, Professor of Social Policy at the University of Newcastle upon Tyne, attended the colloquium throughout the three days, and I would like gratefully to acknowledge his generosity in doing so, his contributions to the debate and his helpful comments on individual chapters. This sharing of ideas and perspectives enabled a richer analysis of complex and multifaceted phenomena to take place. The introductory chapter discusses some of the manifestations of the rise of the market in health care, clarifies some of the concepts and terms used throughout the book, briefly discusses some of the pitfalls of comparative analysis, sets out the contents and scope, and the rationale for the selection of countries examined.

The rise of the market in health care

What a market means in economic theory is discussed at length in Chapter 3, but all markets are also social constructions governed by formal and informal sets of rules and patterns of normative relationships. The core elements of any market are a structure of buyers and sellers, trading goods or services for money. Markets may be more or less competitive, more or less 'free' or subject to regulation by the state or other bodies (e.g. professional or industry associations).

Real health systems are more complex than the crude stereotypes used to describe them (as employed in the opening paragraph), and cannot be adequately described by a state-market or public-private dichotomy. For example, although the British look to the USA as the example par excellence of the market system, over 40 per cent of health spending there passes through government hands, either federal or state (mainly for the financing and administration of Medicare for the elderly, and Medicaid for the indigent) (Newhouse, 1996). Conversely, the American public regard the British National Health Service (NHS) as a prime example of 'socialised medicine' almost akin to the centralised systems of the former Soviet Union, yet at least 52 per cent of health spending by the NHS takes place in the private sector (Salter, 1995). All health systems are a mixture of public and private elements: the rise of the market in health care involves an incremental shift and the selected application of various market 'tools' or instruments to different parts of the health system, rather than a wholesale move from one kind of system to another.

For example, most countries use a combination of different methods to finance health care, but three main methods predominate:

- public finance through general taxation (the 'Beveridge model') used by the UK, New Zealand, the Nordic countries, Canada, Italy and Spain;

- public finance through compulsory social insurance (the 'Bismarck model') used in Germany, the Netherlands, France and Belgium;

- private finance based on voluntary insurance or direct payments, largely used in the USA.

The extent to which the first two methods are supplemented by direct charges or private payments differs considerably from one country to another, but one sign of the rise of the market is the increasing use of co-payments or charges levied on patients. This may be coupled with tighter definitions of what will be provided by the public system, and what will be excluded. In the supposedly 'free' health systems of Europe about 80 million people have supplementary health insurance to cover them for services not provided by the public scheme or to pay for these out-of-pocket expenses (Moran, 1994).

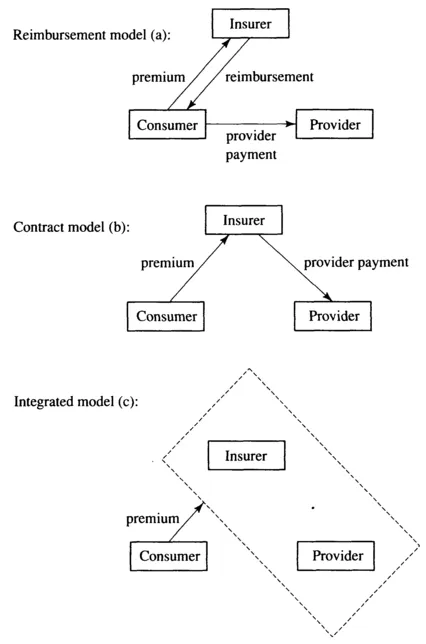

Once the funds for health care are raised, they are reallocated to providers, again by a variety of methods. Given the uncertainty and risks associated with health care - people cannot predict when they will need services and the costs may be very high - the industry is a prime candidate for some form of insurance. The use of intermediaries to bear the financial risks involved, and act as third party payers to providers on behalf of their insured population, is therefore widespread (this is discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3). Who undertakes this role, and the 'risk pools' covered varies considerably: it may be national or regional governments, government appointed bodies, voluntary or charitable organisations or private insurance companies. A useful way to categorise the variety of payment methods in the OECD countries is the classification provided by Hurst (1992), and is shown in a simplified diagrammatic form in Figure 1.1.

In the reimbursement model, used in Belgium and France, consumers pay providers directly and are reimbursed by the insurer, and there is no direct relationship between the provider and insurer. By contrast, in the public contract model, used in the Netherlands and Germany, the insurer contracts directly with providers to supply specified services to consumers. Finally, in the vertically integrated model, the insurer also directly owns and manages the providers, as in the UK National Health Service prior to changes in 1990.

A further sign of the rise of the market in health care has been a move by countries with vertically integrated systems towards the public contract model: putting a 'market' structure in place by splitting the insurance/third party payer function from the provision and management of services, and making providers compete for contracts (so called 'internal 'or 'quasi-markets'). The service providers may either be publicly or privately owned or have charitable status. In countries where the public contract model already exists, the emphasis may be, not on forming but, on 're-forming' the market, with moves to strengthen third party payers and make them more proactive and effective purchasers of care on behalf of consumers. Paradoxically this may entail integrating the purchaser and provider functions in health maintenance organisations and other forms of 'managed care' (discussed below). In some cases, as in parts of Sweden, consumers have been given much greater choice of providers, who are competing for the public funds consumers are indirectly bringing with them. In other cases (the Netherlands, Germany) consumers have also been given greater choice of health insurers, who purchase health care on their behalf.

Figure 1.1 - Three models of paying providers by third-party payers ('insurers)

Source: van der Ven, et al. (1994) p. 1407

Source: van der Ven, et al. (1994) p. 1407

A final example of the rise of the market, alluded to by Moran (1994) is the expansion of private providers in areas where the state had a virtual monopoly in the employment of medical labour, such as Sweden, the UK and New Zealand. This is coupled with an expansion of private providers in other areas: for example contracting out or 'outsourcing' many nonclinical services to the private sector is well-established in the UK, and, increasingly, the use of private capital to build hospitals which will then be leased back to the National Health Service is replacing publicly capitalised investment.

Marketisation or privatisation?

The major focus of this book is the introduction or strengthening of market mechanisms and incentives in the health care systems of a group of advanced Western states. Are these changes to be represented as marketisation or privatisation? Freeman, in Chapter 10, argues that conceptually and analytically these are distinct phenomena, yet they are often used interchangeably because there is little agreement on what we mean by privatisation.

In analysing Conservative approaches to privatisation in the UK, Stephen Young argued in 1986 for a broad definition:

In very broad terms privatisation can be taken to describe a set of policies which aim to limit the role of the public sector and increase the role of the private sector, while improving the performance of the remaining public sector.

(Young, 1986: 236)

Young argued that it was possible to discern seven different forms of privatisation in Conservative policy:

- Outright sales of public assets to the private sector.

- Relaxing state monopolies (deregulation or liberalisation) by changing regulations to allow private providers to enter the market.

- Contracting out or externalisation of services to the private sector, through competitive tendering exercises or other forms of 'market testing'.

- Increasing private provision of services presently monopolised by public providers, which may still be publicly funded.

- Using private investment capital to undertake development projects, for example build hospitals, the Channel Tunnel, etc.

- Reduced subsidies and increased user charges. Consumers pay the total cost or greater proportion of the real cost of providing services.

- Privatising from within - extending private sector practices into the public sector - imbuing the public sector with techniques 'tested developed and refined in market conditions' (Young, 1986: 243).

Although still a useful preliminary categorisation, Young's definition is too broad even for developments in the UK, let alone cross nationally: the planned market experiments between exclusively public providers in Scandinavia were not intended to increase the opportunities for the private sector, for example.

What Young could not foresee perhaps when he wrote this article was the growing importance of initiatives which broadly fall within his category 7 and the international pervasiveness of 'new public management' (NPM) doctrines (Hood, 1991) based on two, sometimes contradictory, streams of thought. The first is the critique of bureaucracy represented by public choice economics which leads in the direction of markets, competition and user choice, either through contracting out, quasi- or internal markets, the increased involvement of private companies and not-for-profits in public service provision and capital investment (Young's categories 2, 3,4 and 5). Secondly there has been a new wave of managerialism based on private sector theories and practices. This has led to a reassertion of management authority over labour, the break-up of traditional government bureaucracies into separate more focused agencies, the extensive use of contracts or quasi-contracts to regulate internal and external relationships, devolution of operational autonomy down the line, the setting of clear standards and measures of performance and a shift towards output controls rather than inputs.

Conceptually it could be argued that the new public management has led to the marketisation of public services by incorporating market methods and incentives into the management of public services in the belief that this will improve their efficiency and effectiveness. As a consequence this may lead also to increasing privatisation, if for example, more contracts are won by the private sector in tendering exercises, or if, in the private financing of public facilities discussed above, there is a transfer of ownership. Indeed, one of the most influential NPM texts, Reinventing Government by Osborne and Gaebler (1992), argued that the role of government should change from being largely a provider of services delivered through state bureaucracies, and become more entrepreneurial and catalytic: governments should 'steer and not row', in their famous phrase. Others, notably the private sector but also the voluntary and community sector, should do the rowing.1 Marketisation and privatisation are not interchangeable concepts therefore but, in practice, one may lead to the other.

'Managed care' and 'managed competition'

The concepts of 'managed care' and ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- The Contributors

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Explaining the rise of the market in health care

- 3 Economic perspectives on markets and health care

- 4 The procompetitive movement in American medical politics

- 5 Canada: markets at the margin

- 6 Reforming the British National Health Service: all change, no change?

- 7 Reforming New Zealand health care

- 8 Managed competition: health care reform in The Netherlands

- 9 Health reform in Sweden: the road beyond cost containment

- 10 The Germany Model: the State and the market in health care reform

- 11 Conclusions

- Index