![]()

1

Culture, Ethnicity, and Personal Relationship Processes: An Introduction

In a special edition of Journal of Social Issues devoted to gender and personal relationships, Winstead and Derlega (1993) declared, “We are born into a gender and into relationships.” As numerous reviews (e.g., T. L. Huston & Geis, 1993; Ickes, 1993; Spence, Deaux, & Helmreich, 1985; Wood, 1995) have indicated, the literature on gender-related personality characteristics, gender-role attitudes, and gender per se as multi-faceted influences on personal relationship processes is rich and voluminous. The rapid growth of this literature since the early 1970s undoubtedly attests to the impact of the Women’s Rights movement of the late 1960s, which in turn owes much of its impetus to the Civil Rights movement of the early 1960s (see Brown, 1986; Spence, et al., 1985).

Few scholars in the field of personal relationships would contest the relevance of gender to academic or lay perceptions of relationship processes (Berscheid, 1994). However, perhaps even fewer scholars in the field seem willing to acknowledge that ethnicity—which, after all, provided the focal point for the Civil Rights movement—also is relevant to the study of personal relationships. Most individuals cannot escape their ethnicity (which many scholars continue to view as equivalent to biological race, especially when considering African Americans; see Landrine & Klonoff, 1996) any more than they can escape their gender (which at least some scholars continue to view as equivalent to biological sex; see French, 1985). Nevertheless, a cursory reading of post-1970s books and articles on personal relationships reveals that ethnicity and related variables (e.g., culture, values) largely have been neglected by personal relationship researchers (Gaines, 1995b).

In this book, my colleagues and I shall examine the ways in which “ethnicity matters” (see West, 1993) as far as genuine understanding of personal relationship processes are concerned. Far from taking for granted the “declining significance of ethnicity” (see Wilson, 1980) vis-à-vis personal relationships, we maintain that culture, values, and ethnicity all are manifested in contemporary relationship contexts in important ways. Moreover, we propose that only by bridging the illusory gaps between the fields of ethnic studies and personal relationships can we as scholars hope to avoid committing the all-too-common “sins of commission” (e.g., falsely assuming that African American or interethnic male-female relationships inherently are dysfunctional); as well as “sins of omission” (e.g., falsely assuming that researchers’ witting or unwitting exclusion of Latina/o or Asian American couples from a given sample is tantamount to searching for “culture-free” truths regarding relationship processes) that plague much theorizing and research on personal relationships.

Laying a Foundation for the Study of Personal Relationships: Interpersonal Attraction as Reflected in Interpersonal Resource Exchange

As Heider (1958) observed, personal relationships are integral to the human experience. People have been fascinated by interpersonal relations since time immemorial. As inherently social beings, we want to understand why people interact with each other in a particular manner. As Berscheid (1985) pointed out, human beings are interested especially in understanding the cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes by which people are attracted to each other. Accordingly, some of the most prominent theories within psychology are concerned implicitly or explicitly with the recurring theme of interpersonal attraction.

Berscheid (1985) provided a useful framework for organizing theoretical perspectives on interpersonal attraction. At the most general level, we can identify “social psychological theories that have predictive implications for a number of social phenomena, including attraction” (p. 426). Among social-psychological theories, those that address reinforcement (Newcomb, 1956) emphasize the extent to which individuals receive tangible and intangible rewards as a result of interactions with their physical and social environments. Among reinforcement theories, those that address social exchange (Homans, 1961) emphasize the extent to which individuals receive tangible and intangible rewards as a result of interactions specifically with their social environments (i.e., with other people). Finally, among social exchange theories, resource exchange theory (Foa & Foa, 1974) emphasizes the extent to which individuals specifically receive intangible rewards (i.e., affection and respect) as a result of interactions with other people.

According to Foa and Foa (1974), people need to be loved and held in esteem by significant others. Among the “commodities” or resources that significant others may possess, affection (i.e., love, or emotional acceptance of another person) and respect (i.e., esteem, or social acceptance of another person) are highly valued. Affectionate behaviors from relationship partners can bolster individuals’ self-love, and respectful behaviors from relationship partners can bolster individuals’ self-esteem. With regard to interpersonal attraction, not only do relationship partners’ affectionate and respectful behaviors per se promote attraction, but the exchange of affectionate and/or respectful behaviors between partners also promotes attraction.

Interestingly, Berscheid (1985) relegated resource exchange theory to an “auxiliary” status among theories relevant to interpersonal attraction. However, the importance accorded to the classification and exchange of intangible rewards as sources of interpersonal attraction suggests that resource exchange theory is an exemplar of what Berscheid (1985) described as specific theories “principally addressed to particular varieties of attraction … and/or to phenomena commonly believed to be associated with attraction” (p. 426). By applying resource exchange theory to the study of interpersonal attraction, therefore, we may gain important insights into human interactions in general and to personal relationship processes in particular.

So far, we have limited our attention to exchange theory (primarily resource exchange theory) as one major reinforcement approach to studying personal relationship processes. Alternatively, reinforcement approaches such as equity theory (Adams, 1963, 1965) and interdependence theory (Kelley & Thibaut, 1978; Thibaut & Kelley, 1959) might be just as relevant to the study of culture, ethnicity, and personal relationship processes. In response to such a critique, we contend that the exchange/equity dichotomy is false; exchange theory (including resource exchange theory) is a form of equity theory (Brown, 1986). Moreover, although recent applications of interdependence theory (e.g., Henderson, 1996; Lin & Rusbult, 1995) show promise as guides to understanding the impact of culture and ethnicity on personal relationship processes, one of the more comprehensive studies to date regarding culture, ethnicity, and relationship processes (Gaines, Rios, Granrose, Bledsoe, Farris, Page, & Garcia, 1996) represents a direct application of social exchange theory in general and resource exchange theory in particular. For these reasons, then, we chose resource exchange theory as one perspective from which to examine culture and ethnicity as predictors of interpersonal behavior within personal relationships.

A Core Model: Interpersonal Resource Exchange in Heterosexual Romantic Relationships

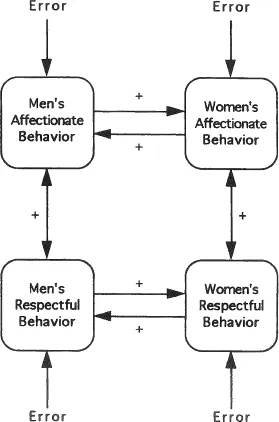

Throughout this book, my colleagues and S shall adopt the perspective that patterns of interpersonal resource exchange characterize heterosexual romantic relationships. In an empirical study of dating and engaged or married couples, Gaines (1996a) reported that (1) women and men tend to reciprocate affectionate behaviors; (2) women and men tend to reciprocate respectful behaviors; (3) women tend to give affection and respect simultaneously; and (4) men tend to give affection and respect simultaneously. From these elements of behavioral covariance, one can construct a core model of interpersonal resource exchange among heterosexual romantic relationships. The resulting core model is presented in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1:

Core model of interpersonal resource exchange

Explicit in the core model of interpersonal resource exchange is the assumption that individuals’ resource-giving behavior is influenced largely by their partners’ resource-giving behavior. A more implicit assumption concerning the core model is that individuals’ resource-giving behavior is not necessarily influenced solely or even primarily by their partners’ resource-giving behavior. In Gaines’s (1996a) study of heterosexual romantic couples, interpersonal traits—especially nurturant or affection-giving traits—explained significant variance in individuals’ affectionate and respectful behaviors beyond the variance explained by partners’ affectionate or respectful behaviors. According to Wiggins (1991), nurturance essentially reflects positive or socially desirable femininity, a gender-related personality trait associated in most people’s minds with women rather than with men (see also Gaines, 1995a; Wiggins & Broughton, 1985; Wiggins & Holzmuller, 1978).

Given that gender-related personality characteristics appear to be reflected in patterns of interpersonal resource exchange, is it also true that cultural value orientations are manifested in interpersonal resource exchange among heterosexual romantic couples? At least one study (Gaines, Rios, et al., 1996) has examined empirical links between cultural values and resource exchange; we shall comment further on that study in Chapter 5 of this book. For now, we can assert that individuals’ resource-giving behaviors are a function of social-psychological attributes that individuals bring into their relationships and of resource-giving behaviors displayed by relationship partners. Such an assertion is consistent with social exchange theory (see Jacobson & Margolin, 1979) and with Lewin’s (1936) field theory (i.e., behavior is a function of the person and of the environment). Once again, we see that resource exchange theory allows us to examine relationship-specific behavior as well as social behavior in general

In this book, we will be concerned primarily with applications of resource exchange theory to heterosexual romantic relationships, particularly those that involve at least one person of color. By limiting our focus in this manner, we inevitably invite criticism regarding the external validity of the models presented in this book beyond heterosexual and/or romantic relationships. A study of same-sex and cross-sex friendships by Gaines (1994b), for example, indicated that reciprocity of respect-related behaviors characterizes male-female friendships but not male-male or female-female friendships. In addition, reciprocity of affection-related behaviors does not appear to characterize any friendships, whether same-sex or cross-sex in nature. Regarding same-sex romantic relationships, we do not know of any study that has examined interpersonal resource exchange among gay or lesbian couples (see Gaines, 1995b; M. Huston & Schwartz, 1995).

Granted the limitations imposed by our emphasis on heterosexual romantic relationships, we encourage our colleagues in the field of personal relationships to ponder the implications raised by the models of culture, ethnicity, and interpersonal resource exchange presented in this book. In some respects, we have chosen the path of least resistance, given that most theories and research on personal relationships take heterosexual romantic relationships as their point of reference (Berscheid, 1985). In other respects, though, we have departed from the practice of focusing mainly upon Anglo couples that typifies scholarship within the field of personal relationships (Gaines, 1995b; Wood & Duck, 1995). We hope that personal relationship theorists and researchers will consider the plausibility of our conceptual models regarding culture, ethnicity, and interpersonal resource exchange—at least within the circumscribed context of heterosexual romantic relationships—and challenge future researchers to test the limits of applicability of our models.

Culture and Ethnicity as Influences on Personal Relationship Processes

In order to demonstrate the need for a conceptually inclusive, empirically testable account of culture and ethnicity as influences on relationship processes, we must first define key concepts and then document the lack of such an account in current theories and research on personal relationships. Culture, according to Ullman (1965), may be defined as “a system of solutions to unlearned problems, as well as of learned problems and their solutions, acquired by members of a recognizable group and shared by them” (p. 5). According to Wilkinson (1993), ethnicity refers to “not only a national heritage but also a distinct set of customs, a language system, beliefs and values, indigenous family traditions, and ceremonials” (p. 19). One additional concept that will be crucial to our understanding of the interplay between culture and ethnicity is that of values, defined by Smith (1991) as “both features of the world toward which people are oriented and … features of people that govern their orientation to the world” (p. 5).

As Reed (1996) has noted, the interplay between culture and ethnicity necessarily is dynamic. That is, the extent to which individuals from a particular ethnic group incorporate the implicit or explicit tenets of a particular culture into their overt and covert behaviors in everyday life may be conceptualized and measured in terms of individuals’ internalized value orientations (Braithwaite & Scott, 1991). As such, values are indicative of the transmission of certain aspects of culture into the social-psychological lives of individuals within a given ethnic group. More germane to the present discussion, though, is the notion that cultural value orientations are abstract and of little practical utility in the lives of individuals within a given ethnic group unless they are manifested in social behavior (Gaines, 1995b).

In Meaningful Relationships: Talking, Sense, and Relating, Duck (1994) made a compelling case for the importance of culture in the relational lives of individuals. Duck observed that cultural values provide individuals within ethnic groups with particular ways of viewing the world as well as expectations regarding individuals’ behavior in a variety of social contexts. This is not to say that all individuals within a specific ethnic group embrace the same cultural values to the same extent. Rathe...