![]()

I

GENERAL PERSPECTIVES

![]()

1

How Might Emotions Affect Learning?

Gordon H. Bower

Stanford University

The relation of emotion to learning and memory is a vast, complex topic. In earlier writings on the topic (e.g., Bower, 1981; Bower & Cohen, 1982; Bower & Mayer, 1989), I have concentrated almost exclusively on the “memory” part of that relationship and used only an informal, layman’s view of emotions. I advanced no particular conceptualization of what an emotion is, what taxonomies of emotions are plausible, what functions emotions might perform in a cognitive system, nor how they might be related to learning in general. Because several commentators have criticized my earlier neglect of these topics, I use this present opportunity to set forth my views on the broader issues of emotion theory before moving on to the more specialized topic of this handbook, namely, the relation of emotion to learning.

THE PLACE OF EMOTION IN A COGNITIVE ARCHITECTURE

One approach to theory development is to consider humans as biological machines endowed with a cognitive system (for acquiring and using knowledge), and to ask what role motives and emotions should play in such a system. This is the approach exemplified in treatments by Frijda (1986; Frijda & Swagerman, 1987), Oatley and Johnson-Laird (1987), Simon (1967), Sloman (1987; Sloman & Croucher, 1981), and Toda (1982). The following discourse borrows heavily from those writings.

Emotion is evolution’s way of giving meaning to our lives. Our lives are ordered and organized by our needs, motives, and concerns. Human actions are guided and motivated, firstly, by biological needs and all the instrumental plans that developed to achieve them, and, secondly, by social-cognitive motives and goals, and plans that issue from them. Evolution has endowed most organisms with inherent nervous mechanisms for detecting and evaluating internal states and external environments as beneficial or harmful to their plans, as reinforcing or punishing. Events come to be evaluated according to the evaluations of the situations they bring about or terminate.

In order to operate successfully in its ecological niche, each goal-seeking biological system needs to have certain design characteristics:

1. The system must have ways to detect the existence and urgency of its different needs and motive states.

2. It must have some means for prioritizing these needs according to their importance, urgency, and delay ability.

3. It must have some planning routines that can either construct an action plan or retrieve one from memory to pursue the satisfaction of whatever motive is accorded the foremost priority. The planner must be able to adjust its action sequence to the multiple constraints of the current situation; and it must be able to plan recursively to create subplans to deal with subgoals as they are generated. This ability requires both an attention controller that allocates processing resources to one among several prospective plans (and thereby inhibits competing plans), and a working memory that can keep track of the organism’s place in its currently active plan as well as hold the stack of goals and subgoals it may generate while planning and/or executing a plan. The more adaptive, “intelligent” planners will be able to foresee and have methods to resolve conflicting plans, to schedule work on plans (e.g., allocating times of the day to work on them), and to create compromise plans that can satisfy several goals concurrently.

4. The organism should have some sensors that monitor its internal and external environment for signals implicating its important concerns, and an ability to interrupt or suspend an ongoing plan in order to deal with an urgent crisis, whether positive or negative. This characterizes opportunistic planners that have a collection of resident goals prepared to be triggered whenever their appropriate goal-stimulus happens by.

A system without these components will perish when confronted with an uncertain, largely hostile environment within which it must pursue satisfaction of its biological motives and concerns. A system with these components will exhibit “emotions” as a by-product of translating its concerns into goal-directed actions in such an unpredictable environment (Frijda, 1986, especially champions this view). Events appraised as achieving its concerns, or aiding plans to achieve them, lead to the positive emotions of pleasure, pride, delight, relief, and enjoyment. Events appraised as thwarting a plan, causing injury or loss of a goal-state, lead to the negative emotions of sadness, fear, and anger. The specific emotion depends on the circumstances and the cognitions surrounding the event.

The unpredictability of the environment plays a central role in the life of the emotions. Our best laid plans oft go awry because unanticipated events create new outcomes or block expected ones, leading to the largely negative emotions. Our emotional reactions are triggered by “computational demons” in the brain that monitor how our plans are faring during execution, whether they are progressing towards their anticipated conclusions, whether a given plan is taking too much time or effort, whether some goal has become unattainable, whether the outcomes match the intended goal-objects or goal-states, and so on. A given plan may fail because it was blocked or thwarted by an adversary (leading to anger); an expected goal-object may not be forthcoming (leading to disappointment or sadness); a new event may threaten us with injury, harm, or rejection (leading to fear).

In computational models of the system (e.g., Bower & Cohen, 1982; Dyer, 1987; Frijda & Swagerman, 1987), the emotional demons can be represented by a collection of production rules that specify a class of external situations that will be recognized as ones appropriate for turning on that emotion. For example, one rule for triggering an “anger demon” would recognize when someone deliberately harms us or causes us unpleasantness. Upon matching such a situation, the rule would fire, causing activation of an “anger emotion” in the system. In an earlier paper (Bower, 1981), this process was modeled as the activation of a specific emotion unit or node connected into an associative network.

Upon activation of a given emotion in a given situation, a collection of memories and a repertoire of action plans will be activated. In the classical learning theories of Hull (1943) and Estes (1958), motive (drive) states were presumed to have corresponding internal drive stimuli that entered into, and activated, stimulus-response associations. In particular, for biological motives like hunger and thirst, the responses associated to the drive stimulus would be those that in the past had been followed by reduction of the drive via successful consummation of the goal-object (the so-called “drive reduction” theory of reinforcement; see Miller, 1951).

For humans, an important kind of memory triggered by a primary emotional or motivational condition is the person’s estimate (based on past experience) of his or her ability to cope with whatever threat has just arisen. Comparing a threat or danger to one’s ability to cope with it is the process called secondary appraisal (by Lazarus, 1966), and it can either reduce or heighten the emotional activation caused by the initial threat.

The repertoire of responses made available by an emotional signal consists of several types. First, for signals of imminent injury, organisms have fast, preprogrammed reflexes for exhibiting startle (flinching, ducking, shrieking), orienting (pausing to listen intently, freezing), and possibly fleeing (running away) or fighting. These early reflexes are fast, often preemptive, difficult to inhibit, and associated with innate facial expressions. Second, as noted before, the action plans retrieved from memory are those that in the past have been generally appropriate to that motive or emotion in similar situations. The general plan is to approach and maintain contact with sources of positive emotions (e.g., good tastes, pleasant friends, beautiful scenery) and to remove or escape from sources of negative emotions. For example, fear retrieves plans for avoiding the danger, minimizing the threat, escaping the harm; anger retrieves plans for circumventing the frustration, removing or overcoming an obstacle, taking revenge upon an offending perpetrator. Many of these action plans are social and require interactions with others, to enlist aid, invite sympathy, bargain, intimidate, threaten, provide rewards (smiling), and so forth. Facial expressions of emotions often function for social communication between individuals; by appraising someone’s facial expression, we pick up clues as to how to smooth or coordinate our interactions with them. We use the boss’ facial expression to tell us whether it is best to ask for a raise now or to postpone the request.

Of particular interest to this chapter is the relation between the emotional or motivational state and the memories that it may call to mind. We return to this topic later after a digression on the development of emotions.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF EMOTIONS

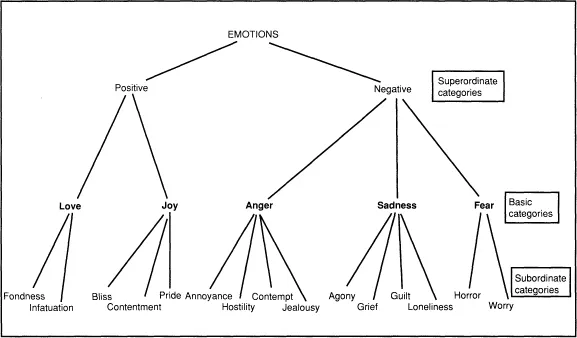

Human emotions and emotional responses develop by a long process of acculturation acting upon an infant’s biological substrate. Infant researchers agree that within the first year of life human infants display the facial expressions and gross action patterns appropriate to basic emotions such as fear, anger, sadness, affection, and joy. These emotions can be elicited by reasonably simple stimuli (e.g., a loud startling noise; confinement of movements; tickling), they have an almost reflex-like quality and tend to be cross-cultural. As time passes, infants develop a broader range of emotions and a more complex, differentiated set of emotional appraisals involving more culturally specific interpretations of situations involving emotional displays. Different observers have classified and organized these inter-related families of appraisals into hierarchies of emotional categories. For example, Shaver, Schwartz, Kirson, and O’Connor (1987) proposed a hierarchy with three layers, from superordinate (groupings of positive or negative emotions) to basic, universal emotions, thence to subordinate emotions (more differentiated and specific to different situations). Their proposed hierarchy is depicted in Fig. 1.1.

The basic emotions are presumably universal, biologically based, present from infancy, and have associated facial expressions and primitive action scripts. Their names are typically the first emotion words that children learn, and words referring to them (or close equivalents) exist in most cultures. One can dispute whether Fig. 1.1 has listed all the basic emotions (for example, Ekman, 1984, would add disgust to the list). However, the general layout of the emotion domain in Fig. 1.1 seems intuitively compelling.

The superordinate groupings into positive and negative emotions abstractly characterize events that either produce beneficial gains or noxious losses. In behavioristic parlance, they describe positive or negative reinforcers. Children appear to learn very early labels to apply to people, events, and situations that arouse these generic emotions: They are termed nice, like, good versus bad, mean, don’t like. This positive/negative polarity exists in all cultures and seems fundamental to human cognition (see, e.g., Osgood, Suci, & Tannenbaum, 1957).

FIG. 1.1. A simplified version of the emotion hierarchy reported by Shaver et al. (1987). Only a few of the subordinate emotions are included here. (Reproduced by permission from “How emotions develop and how they organize development,” by K. W. Fischer, P. R. Shaver, & P. Carnochan, in Cognition and Emotion, 4, 1990, 81–127.)

The subordinate emotions (only a few are shown in Fig. 1.1) develop in later years as differentiations and refinements within the basic-level categories. These are often more complex, socially constructed emotions such as pride, jealousy, resentment, and guilt. Children only gradually learn how to apply labels for subordinate emotions as they come to discriminate relevant features of social success versus failure, of accidental versus intentional actions, and of moral responsibility (see Stein & Levine, 1989). The subordinate emotions display considerable variation across cultures and across different historical periods within a culture. Some subordinate terms designate a constellation of basic emotions elicited in a given social relationship; for example, jealousy involves both fear of loss (of a loved one) and anger at the loved one for threatening to withdraw his or her affection.

Taxonomies of Emotion Terms

Attempts to classify human emotions and to analyze their subtypes inevitably encounter the vagaries of emotional language, and the imprecise way linguistic terms map onto human experience (e.g., Fehr & Russell, 1984). For all practical purposes, human experience is infinitely diverse; yet, to communicate we need some words and concepts to classify our many experiences. There are over 600 words in English alone referring to affective experiences; yet few of us would claim that there are that many distinctly different types of emotions. But how can one decide what is to serve as a label for a basic emotion in a hierarchy such as Fig. 1.1? What is to count as the name of an emotion as distinct from some alternative type of psychological state?

The classification and taxonomy of the emotion domain is a topic of currently active debate. One attractive taxonomy provided by Johnson-Laird and Oatley (1989; Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987), identifies five basic or primitive emotions. Each emotion corresponds to some juncture in the goal-planning process. Specifically, happiness arises when some goal is achieved, sadness when some major goal is lost or plan fails, anxiety when a self-preservation goal is threatened, anger when an active plan is frustrated, and disgust when a gustatory goal is violated (see Oatley & Johnson-Laird, 1987, Table 1, p. 36).

Another taxonomy, provided by Ortony, Clore, and Collins (1988; also Clore & Ortony, 1988), followed upon an earlier semantic analysis of the affective lexicon by Ortony, Clore, and Foss (1987). These authors start with the observation that the 600-plus items in the affective lexicon comprise an amalgam of poetic metaphors, slang, extensions, historical accidents, and conceptual confusions. They argue that any serious scientific investigation must begin by carefully distinguishing between what is “properly” considered to be an emotion term as opposed to the many nonemotional terms found amongst the affective lexicon of English. The taxonomy of Ortony et al. (1987) distinguishes, first, between terms referring to external conditions that may cause emotions as opposed to internal conditions. Thus, terms like abandoned, neglected, lonely, guilty, safe, or quiet refer first and foremost to objective factual descriptions of a person’s situation or behavior but are not themselves emotion terms. They are judged to be not emotion terms because it is entirely sensible for them to fit in the frame “I am X even though I do not feel X.” An alternative indicator is that people rate “feeling x” (guilty, abandoned, etc.) as more like a prototypical emotion than “being X.” Thus, although “feeling abandoned” may refer to a complex of emotions (such as fear and sadness) typically associated with a given external condition, abandoned itself does not designate a basic emotion. It appeared to be an emotion term only because of various tricks of ellipsis in English, whereby expressions like “I’m lonely” come to serve as short-hand for “I have those feelings typically experienced by someone who believes he or she is alone and who does not like it.”

A second distinction in their taxonomy is between words describing mental versus nonmental conditions. The latter include terms referring to physical and bodily states such as sleepy, nauseous, aroused, and faint. Subjects rated these either as not emotions at all or as very poor examples. In further semantic brush clearing, Ortony et al. (1987) noted distinctions between affective terms that refer to occurrent states (that might be emotions) versus traits, the latter referring to long-term dispositions or frames of mind, capt...