Cognitive Abilities in Neurocognitive Perspective: The Atomistic View

People who work with people with dementia and their caregivers often find themselves in a curious dilemma: We (that is, researchers, students, medical and rehabilitation professionals) learn about ‘memory’, ‘cognition’, ‘brain disease’, and so forth through the perspectives of medicine, neuropsychology, psychiatry, or cognitive science, depending on our pathways through education, and these perspectives tend to have certain elements in common: by and large, they are tidy, they are atomistic and focus on categorization and dissociation, and they seek to generalize. And then we have to explain to so-called ‘lay’ persons what it all means. What does the diagnosis of ‘probable dementia of the Alzheimer’s type’ mean for my grandmother? What does it mean to have an MMSE score of 16? What does it mean when I’m told that I can expect that my father’s procedural memory and motor learning skills are likely to remain more intact for longer than his word-finding, verbal fluency, and short term memory? How is this going to translate into ‘real life’?

The atomistic, dissociation-focused view of cognitive and linguistic impairment (or skill, for that matter) is grounded in what Luria (1987a, b) referred to as ‘classical science’ (see also Sabat’s [2001] discussion of ‘classical’ versus ‘romantic’ science as applied to Alzheimer’s disease, with more detailed discussion of Luria’s distinction). The ‘classical’ approach, which for centuries has dominated mainstream medical and psychological research and practice, attempts to reconcile two basic strands of reasoning: one of generalization, and one of isolation. In terms of generalization, one attempts to isolate the common denominator in a category of people (defined by a complex of symptoms). Thus, people with recurring severe headaches, often confined to one side of the head, and in many individuals accompanied by one or several other symptoms, such as light aversion, nausea, and visual hallucinations (among others), might be diagnosed with recurring migraines, and thereby a category label is assigned to a symptom complex. Further investigation might reveal contributing causal factors: one individual may have allergic reactions to certain foods; in another, severe stress may be a trigger. The search for generalization is thus subserved by the search for isolable, and dissociable, factors or variables.

Dissociation of Memory Types

Students of dementia learn that memory impairment is a key impairment in dementing conditions. Further, we learn that memory is not a monolithic phenomenon, but rather that different subsystems of memory can be distinguished and experimentally verified and that separate memory subsystems are linked to specific neurological substrates and can be differentially impaired in different subtypes of memory disorder. The models developed by Baddeley, Squire, and colleagues have widespread currency in dementia studies (see, e.g., Squire, 1987, 2004; Squire & Kandel, 1999; Baddeley, 2002). A fundamental distinction is that between short term memory (STM) and long term memory (LTM). Two major components of STM are immediate memory and working memory. Immediate memory has a very limited storage capacity, both in terms of discrete units and time before information is lost (an upper limit of seven units, and less than 30 seconds unless information is rehearsed, are often cited; see, e.g., Squire & Kandel, 1999). The concept of working memory was established mainly through the work of Baddeley and colleagues (e.g., Baddeley, 2002, with earlier references). Working memory (WM) is understood as an information buffering center where information is held in conscious awareness, reviewed, and manipulated. Separate WM subsystems are distinguished: In the phonological input store, auditory traces are held active for a short time, and the articulatory loop serves as a subvocal rehearsal faculty. Visual and spatial information is kept active in the visuospatial sketchpad. The episodic buffer is an intermediary processor between WM and LTM. Further, Baddeley and colleagues distinguish a central executive, that is, a system that enables a person to focus attention, to access and retrieve information in long term storage, and to encode information and thus underlies the ability to make decisions and plans.

Researchers and diagnosticians distinguish two primary subsystems of LTM, namely declarative and non-declarative, or explicit and implicit memory systems. What the subsystems of non-declarative or implicit memory have in common is that they are generally considered not to be available for conscious, volitional review. Proverbial procedural skills are, for instance, those of swimming, or of riding a bicycle, that is, motor skill memories. These activities are learned by doing, rather than by conscious cognitive effort, reflection, or manipulation of information. They are also highly automatized, and once mastered, it is extremely unlikely that they are ‘unlearned’; in other words, one doesn’t ‘forget’ how to swim or ride a bicycle (what may become impaired, however, are other abilities that enable the execution of the skill, such as muscle function, balance, or vision). Other aspects of non-declarative memory are cognitive skills that are active without a person’s conscious awareness, priming, habitual behaviors, and conditioned behaviors.

Declarative or explicit memory is knowledge about the world that is open to conscious review. Three distinct subsystems are distinguished: Semantic memory is memory for concepts and how they relate to each other, by way of propositions and schemata. Episodic memory is memory for events or episodes; one way to conceptualize it is as “semantic memory plus a context” (Bayles & Tomoeda, 2007, p. 42). Lexical memory is memory for words, their meanings, pronunciation, spelling, and cross-language equivalents or rough equivalents. Thus the word ‘bicycle’, and its German and Afrikaans counterparts ‘Fahrrad’ and ‘fiets’, respectively, are instances of lexical memory; these are of course closely related to the concept (an instance of semantic memory) of a two-wheeled vehicle powered by a pedal-and-chain transmission, with a handlebar and saddle, and prototypically built for single-person use. The memory of riding one’s bicycle to work on a sunny day last week is an instance of an episode, or a concept with a context.

In the neuropsychology of memory and dementia, much research has been devoted to the discovery of which neural substrates support which memory system, and the breakdown of which neurological structures is responsible for which facet of memory impairment in dementing conditions. We shall not pursue this aspect of memory science further here; reference to specific brain lesions will be made in individual chapters of this collection where necessary (for overviews, see, e.g., Becker & Overmann, 2002; Bayles & Tomoeda, 2007).

Neurocognitive Assessment and Diagnostic Translation

Assessment of cognitive and language functions in the context of dementia pursues multiple aims. Examiners look for the presence of dementia as evidenced by the balance of cognitive and communicative deficits and preserved skills. This balance serves to establish a baseline of deficits and skills that informs the assignment of a diagnostic label, such as dementia, or a specific dementia subtype, such as dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Further, the baseline informs intervention, whether pharmacological or behavioral, as well as the measurement of intervention efficacy (which is of course tricky in progressive conditions). In addition, there also needs to be a counseling aspect, both for the individual (to be) diagnosed and those who will most closely be involved with (future) caregiving; this latter will typically involve questions on the part of the person with suspected dementia, and their caregivers, what the likely path of future decline will look like (see, e.g., Tomoeda, 2001; Bayles & Tomoeda, 2007).

In the absence of sudden onset of cognitive, memory, or language deficit that can be linked to a clear precipitating event, the diagnosis of dementia, and any one subtype of dementia is essentially one of elimination.1 As well as a process of elimination, medical diagnosis of dementia is also a process of decontextualization: An individual may experience concerns about cognitive deterioration in daily life (‘I keep forgetting appointments’; ‘I can’t seem to remember things I did or said a minute ago’; ‘it’s getting so hard to do sums in my head’). She may approach her primary care physician with these concerns, who may refer her to a neurologist. An examination involving brain scan comes back as normal, as do other physiological measures (e.g., screening for endocrine function, infections, or deficit states). At this stage, a case is made for thorough neuropsychological assessment, which in essence consists in the search for functional deficits of cognitive subsystems, such as short term memory, or executive function, which in turn have been established in the diagnostic literature as to be measured independently of contextual influence.

To the ‘lay’ mind, the cycle of assessment of cognitive skills and determination of functional consequences may appear somewhat circular: an individual may be concerned because she is finding it progressively more stressful and difficult to drive in busy traffic or unfamiliar surroundings, or because she finds she ‘gets lost’ when she attempts to prepare a complicated meal. Her concerns are duly taken note of and verified through neuropsychological examination, which reveals moderately severe deficits on measures of immediate and delayed recall, complex attention, and of processing speed and reaction time, and she is counseled that these deficits are likely to have an impact on complex tasks, for instance, driving or cooking.

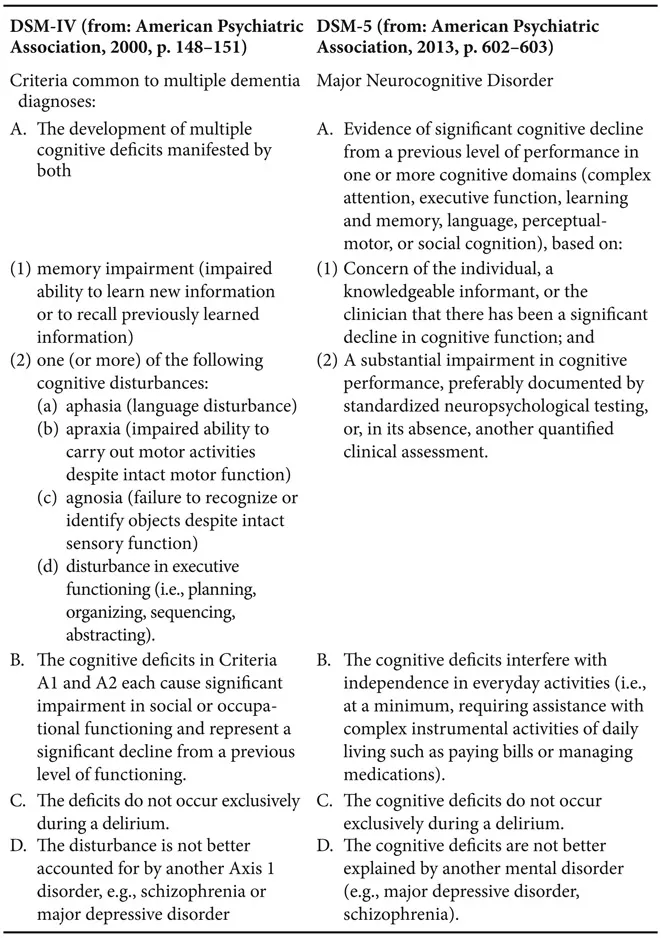

An Example of Diagnostic Categorization and Labeling: The DSM

The standard reference work used in the US context for the diagnosis and classification of dementia and its subtypes is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM. The fourth edition, text revision (DSM-IV-TR; henceforth DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2000) of this work was in current use at the time of chapter preparation, with the fifth edition (DSM-5, APA, 2013) just published before this volume went to press. DSM-5 introduced substantial revisions of several major diagnostic categories, among them dementia, and was published among a flurry of (at times very critical) discussion in various quarters, such as the US National Institutes of Mental Health.2 In Table 1.1, we offer a brief side-by-side comparison of DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. In DSM-IV, the superordinate category for dementia and its subtypes is “Delirium, Dementia, Amnestic, and Other Cognitive Disorders.” DSM-5 introduces the superordinate category Neurocognitive Disorder (NCD), which includes delirium (which we don’t discuss any further in this collection), major NCD and mild NCD, and their etiological subcategories. The defining difference between major and mild NCD is that the former involves “significant cognitive decline from a previous level of functioning” and the associated deficits “interfere with independence in everyday activities,” whereas in the latter, cognitive decline is “modest” and does “not interfere with capacity for independence in everyday activities” (APA, 2013, p. 602, 605). DSM-5 makes the caveat that “the distinction between major and mild NCD is inherently arbitrary” and “the disorders exist along a continuum” (APA, 2013, p. 608).

The major categorical and terminological change in DSM-5 is obviously the removal of the term dementia as the label for the superordinate diagnostic category, although DSM-5 states that the “term dementia is retained in DSM-5 for continuity and may be used in settings where physicians and patients are accustomed to this term” (APA, 2013, p. 591). According to a report by the DSM-5 Neurocognitive Disorders Work Group, one motivation for this change was the “pejorative / stigmatizing connotation” associated with the term dementia (Jeste et al., 2010, p. 7).

While in earlier versions of DSM, memory impairment was treated as the core and defining symptom, DSM-5 removes memory impairment from the focal position and bases diagnostic criteria for the various subtypes of NCD around a set of six cognitive domains (see Table 1.1). While memory impairment is of course the hallmark symptom of dementia of the Alzheimer’s type (NCD due to Alzheimer’s disease, in DSM-5 terms), in other NCDs (such as frontotemporal degeneration), memory may be impaired relatively late in disease progression (or not at all), whereas other domains, for instance executive function or language, may be impaired much earlier (Jeste et al., 2010, p. 7).

DSM-5 criteria aim to be more specific than previously in terms of the evidence used to establish a diagnosis, requiring both observational evidence (patient, informant, and/or clinician concern) as well as

Table 1.1 Comparison of DSM-IV and DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Dementia versus Major Neurocognitive Disorder

objective assessment (for major NCD defined as performance of > 2.0 SD below the mean, or 3rd percentile or below of an appropriate reference population, on a domain specific test; for minor NCD, defined as performance between 1–2 SD below appropriate norms, or between the 3rd and 16th percentiles).

Potentially the most far-reaching innovation in DSM-5 is the inclusion of the category of mild NCD, for which there is no direct equivalent in earlier DSM editions. This category is to apply to persons who present with identifiable levels of cognitive impairment that are, however, not sufficiently severe to warrant the diagnosis of major NCD; the change being “driven by the need of such individuals for care, and by clinical; epidemiological; and radiological, pathological and biomarker research data suggesting that such a syndrome is a valid clinical entity with prognostic and potentially therapeutic implications” (Jeste et al., 2010, p. 9). Table 1.2 illustrates how the differentiation between major and mild NCD is applied to the specific etiology of Alzheimer’s disease, in comparison with the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for dementia of the Alzheimer’s type.

The category mild NCD due to Alzheimer’s disease clearly looks to the future of biochemical brain research and imaging research to support reliable early di...