![]()

PART 1

PERSPECTIVES

![]()

There are no rules or recipes that will guarantee successful curriculum development. Judgment is always required, and if this task is a group effort, sensitivity to one’s fellow workers is always necessary.

—Elliot Eisner, American scholar of education

The Educational Imagination, Third Edition, 1994

Questions

• What is a curriculum?

• Why do people care so much about curriculum issues?

• What kinds of work do people do in connection with curriculums?

• Who does curriculum work?

• What are the challenges of curriculum work?

• What can professionals learn that will help them do better curriculum work?

People Care about Curriculum

People demand action on curriculum matters, the media report these demands, and public officials and schools respond. What better evidence could there be that people care deeply about curriculum matters? Here, for example, are several news stories that report people demanding curriculum changes. These all appeared in the New York Times in 1999, but the Times and other news media report similar stories every year.

• “Schools Taking Tougher Stance with Standards” (September 6, 1999)

“No more fun and games: As children across the nation head back to school this fall, many are encountering a harsher atmosphere in which states set specific academic standards and impose real penalties on those who do not meet them.”

Americans often worry that children may leave school unprepared for work or higher education. As the demands of work and higher education increase, most Americans believe that public schools need to offer a more academically demanding curriculum.

• “Amid Clamor for Computer in Every Classroom, Some Dissenting Voices” (March 17, 1999)

Computers arejustoneexampleofmanychangesinhow people workandlivethat provoke calls for curriculum change. Most Americans believe that schools should at least consider changing their curriculums to reflect these changesinsociety, although individuals may disagree about whether a particular change is a good idea.

• “Board for Kansas Deletes Evolution from Curriculum” (August 12, 1999)

“The Kansas Board of Education voted yesterday to delete virtually any mention of evolution from the state’s science curriculum.…”

“Science vs. the Bible: Debate Moves to the Cosmos” (October 10, 1999)

“Scientific lessons about the origins of life have long been challenged in public schools, but some Bible literalists are now adding the reigning theory about the origin of the universe to their list of targets.”

Most Americans want schools to teach established truths and values that we all share. They shy away from teaching that contradicts religious convictions or that offends any racial, ethnic, or cultural group. Yet views change, and sometimes the public eventually accepts ideas that once were controversial. Conversely, views that once were accepted sometimes become offensive when sensibilities change. Most Americans believe that the school curriculum should be updated to reflect currently accepted views of what is true, just, and important, but when is it appropriate for schools to impose on dissenters views accepted by the majority?

• “A Gap in the Curriculum” (April 26, 1999)

“The ghastly horror in Littleton, Colorado, makes all of us repeat our favorite remedies for eliminating violence….” (The article concludes that schools need to help students resolve conflicts and deal with emotionally charged issues.)

“Earlier Work with Children Steers Them from Crime” (March 15, 1999)

“Programs that seek to reduce violence, drug abuse, pregnancy and other dangerous or unhealthy activities among adolescents are notorious for doing too little too late and at too great a cost. But a new study has shown that by starting early….”

Whenever many children seem to be having trouble, advocates call on schools to solve these problems. Americans often support curriculum changes intended to help children address nonacademic problems such as alcohol and drug abuse, teenage sex, reckless driving, smoking, and readiness for the world of work.

• “Serving the Less Fortunate for Credit and Just Because” (April 4, 1999)

“For the last few years, Stacy Joseph, a senior at Half Hollow Hills West High School, has volunteered regularly at a soup kitchen….” (The article goes on to describe community service opportunities offered in schools for academic credit.)

When a community feels itself to be in trouble, locals often demand that the schools address the community’s problems. Communities expect schools to help them address poverty, crime, threats to public health, a waning sense of community, and needs for cultural enrichment. Many communities also expect schools to prepare young people for jobs in industries important to the local economy.

Curriculum Work Today

A curriculum is a particular way of ordering content and purposes for teaching and learning in schools. A common curriculum responds to a deep need that many Americans feel to offer all young people a common foundation of essential knowledge and skill. Curriculum work is important because the curriculum affects what teachers teach and thus what students learn, and in so doing it helps to shape our identity and our future. Curriculums require a lot of work—debating ideas for curriculum change, creating curriculum plans, seeking agreement from important stakeholders on those plans, bringing those plans to life in classrooms and schools, and studying curriculums and their effects.

Curriculum work succeeds when teachers and students enact a curriculum in the classroom that leads students to learn the intended content and achieve the intended purposes and that pleases teachers, school leaders, parents, and the public. Therefore, curriculum work is fundamentally work with and for teachers, but it also requires agreement and cooperation from many other stakeholders including students, parents, school officials, accrediting agencies, university admissions committees, and employers, among others. These stakeholders embrace various educational ideals, such as academic excellence, equality, and social relevance, and these ideals lead them to push for different curriculums. Many people feel strongly about curriculum matters and are willing to fight for their priorities, so curriculum work is often contentious. In schools, curriculum work is segmented by subject and by age or grade level and must often be done with very limited time and money. These conditions make curriculum work in today’s schools very challenging.

While curriculum work remains the same in many ways today as it has been for a half-century or more, several strong currents of change in education are changing curriculum work and portend a transformation in the near future. Public expectations for education are rising. A movement is underway to establish a system of national standards and to develop tests that will determine whether children have achieved these standards. Educational issues, especially curriculum issues, are increasingly being fought out in the political arena, with mayors, governors, state and federal legislators, and presidential candidates playing leading roles. The public is showing greater willingness to experiment with new educational institutions such as charter schools, home schooling, and vouchers. The teaching force is changing as older teachers retire and new ones enter the profession by various routes. New forms of information technology are making computer-assisted instruction, distance learning, and other new forms of teaching and learning possible. Also, new ways of thinking about teaching and learning based on cognitive science and brain research are leading to designs for more powerful learning environments and better ways to assess learning. These developments create exciting new challenges and opportunities for curriculum specialists. Effective curriculum work in this new environment will require a mixture of old and new knowledge and skill.

What is a Curriculum?

A curriculum is a particular way of ordering content and purposes for teaching and learning in schools. Content is what teachers and students pay attention to when they are teaching and learning. Content can be described as a list of school subjects or, more specifically as a list of topics, themes, concepts, or works to be covered. Purposes are the reasons for teaching the content. Among broad reasons for teaching school subjects are to transmit the culture, to improve society, or to realize the potential of individual students. More fine-grained purposes for studying particular topics are usually stated as specific goals or objectives students should attain. Content and purposes can be ordered in many ways, including the tight, hierarchical ordering common in mathematics, the linear ordering by time that is often used in history, and the broad themes common in literature or social studies.

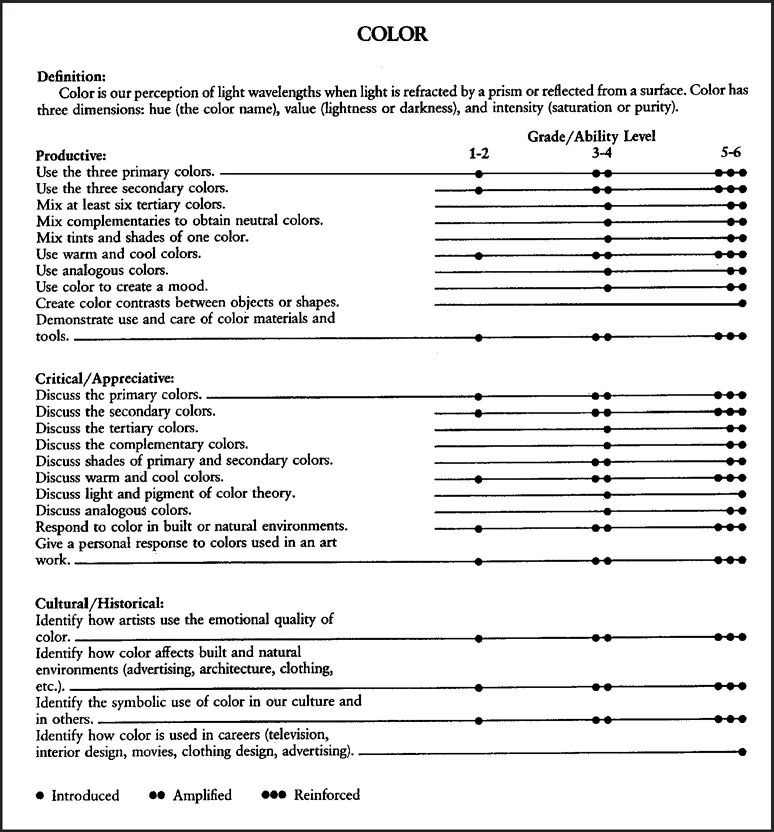

FIG. 1.1. A scope and sequence chart in elementary school art.

This chart lists objectives grouped in three broad domains (productive, critical/appreciative, and cultural/historical) and indicates when each is to be taught.

SOURCE: Arizona Art Education Association, 1982, Fall. Art in Elementary Education: What the Law Requires, InPerspective, The Journal of the Arizona Art Education Association 1:6–24.

Ask to see a school’s curriculum and you may be shown any of several kinds of documents, including:

• a list of courses offered or subjects taught,

• a weekly or yearly schedule of when various subjects are taught,

• a scope and sequence chart such as the one in Fig. 1.1, which combines a list of topics with a timeline showing when each is taught,

• a collection of textbooks or teachers’ guides.

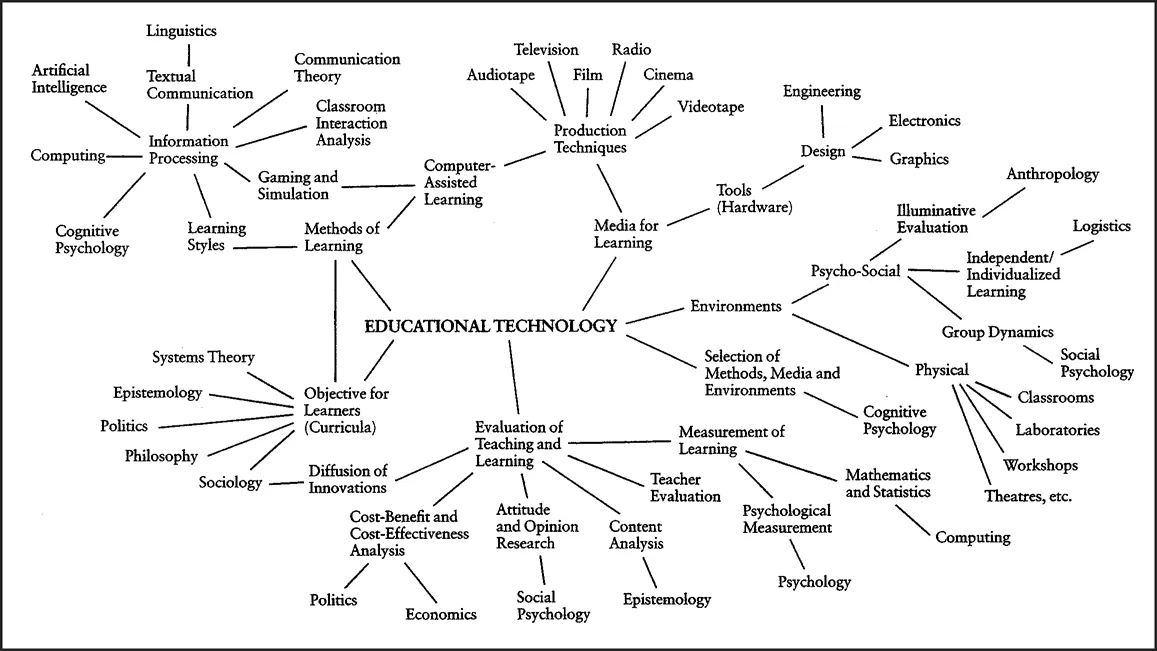

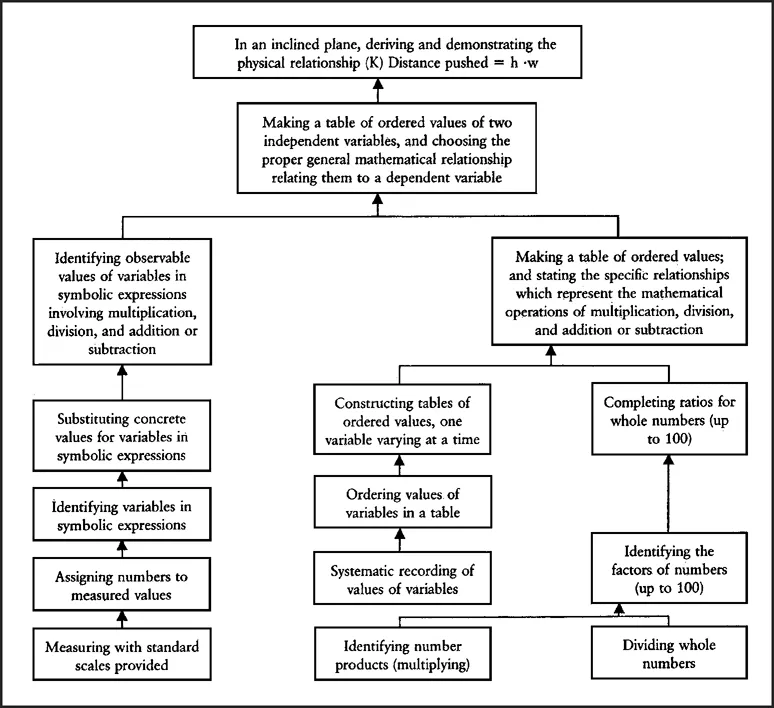

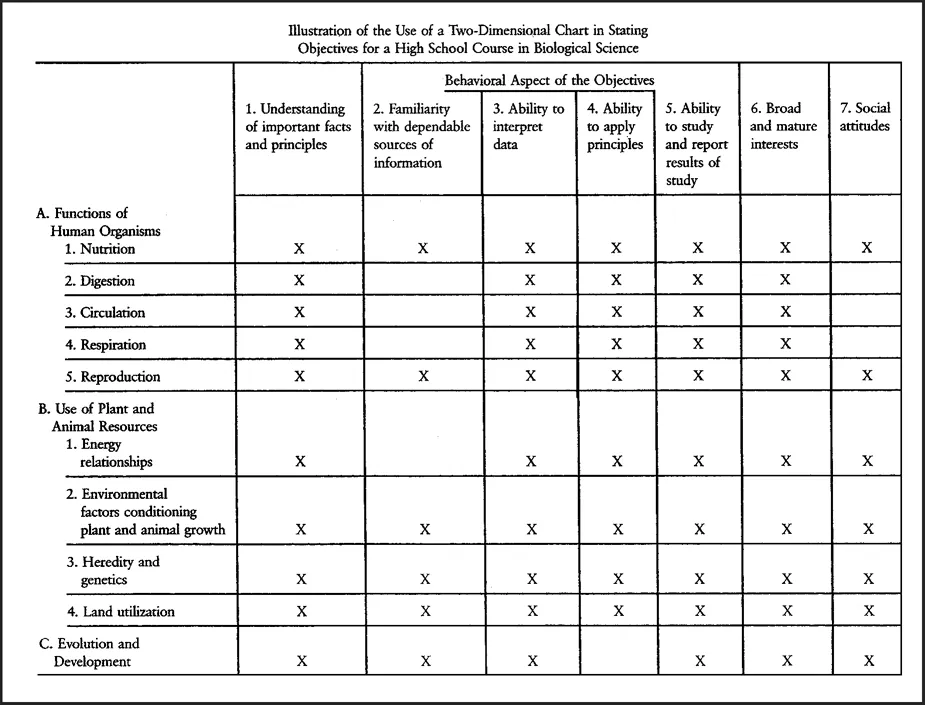

Curriculum planners often represent the elements of a curriculum in more specialized ways. They may use a concept map such as the one in Fig. 1.2 to represent relationships among items of content. They may use a diagram such as the one in Fig. 1.3 or a content x behavior grid such as the one in Fig. 1.4 to show relationships between content and purposes.

FIG. 1.2. A concept map of educational technology.

SOURCE: Hawridge, David, 1981. The Telesis of Educational Technology. British Journal of Educational Technology 12:4–18.

FIG. 1.3. A hierarchy of educational purposes.

SOURCE: Weigand, V. K. 1970. A Study of Subordinate Skills in Science Problem Solving (Robert M. Gagne, ed.) Basic Studies of Learning Hierarchies in School Subjects. Berkeley: University of California.

Such curriculum documents coordinate teaching and learning in vital ways. They help teachers keep in mind the big picture of what should be taught and learned over months and years and keep track of where they are in relation to planned progress at any given time. They remind teachers of why each topic is being taught. They help teachers coordinate their work with that of other teachers. They inform parents, school officials, and interested persons outside the school about what students are studying and when. By providing a coordinating structure, curriculum documents help to bring a degree of order and predictability into a far-flung educational system that would otherwise be more bewildering for everyone involved.

The curriculum is a quiet, almost imperceptible presence in every classroom. Experienced teachers rarely need to consult curriculum documents because they have internalized them. Curriculum documents play a vital role for new teachers, but this role remains behind the scenes, invisible to classroom visitors. Visible or not, curriculum guides, frameworks, textbooks, tests, and similar written and unwritten expectations impinge in some way on almost everything teachers do.

FIG. 1.4. A content x behavior grid for high school biology.

SOURCE: Tyler, Ralph. 1949. Basic Principles of Curriculum and Instruction. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

The following fictional story about a new teacher shows some of the ways that a curriculum works through teachers to shape what happens in classrooms. The story compresses into one occasion many experiences that would normally occur over the first few weeks of teaching when novice teachers confront directly many factors originating outside the classroom that guide and constrain what they and their students will do there.

A New Teacher Meets a School Curriculum

Terry arrives at Washington Middle School for the first official day of her first teaching job. Today is a day for teachers to get ready. Students come next week. Terry meets her department chair for a scheduled orientation to teaching in the department. Margaret greets Terry cheerfully and gets right down to business.

“Hello,...