This is a test

- 304 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Art and the Christian Apocrypha

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Christian canon of scripture, known as the New Testament, excluded many of the Church's traditional stories about its origins. Although not in the Bible, these popular stories have had a powerful influence on the Church's traditions and theology, and a particularly marked effect on visual representations of Christian belief. This book provides a lucid introduction to the relationship between the apocryphal texts and the paintings, mosaics, and sculpture in which they are frequently paralleled, and which have been so significant in transmitting these non-Biblical stories to generations of churchgoers.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Art and the Christian Apocrypha by David R. Cartlidge, J. Keith Elliot in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia antica. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Text, Art and the Christian Apocrypha

Christian theology has elevated the rhetorical arts in written form to the predominant position in its traditions. In addition, most Christians have a canon of written texts which they declare to be exclusively the rule and practice in the church’s life, although not all Christians agree on the contents of the canonical list of the Old Testament. New manuscript discoveries such as the Nag Hammadi codices have enlivened continuing discussions of the theological validity or wisdom of a ‘closed canon.’1

None of the above is news. That most Christians possess a canon of written literature and confess this canon to be the required basis by which to judge all other forms of faith and practice raises at least two problem areas for this particular study. Our subject is (1) the importance of extra-canonical traditions in (2) their iconic forms.

The church, the chirograph and the other arts

The church turned to the chirograph, that is, the written text, from its foundational art forms, namely from oral tradition in narrative (stories) and poetry.2 The consequences of this shift of medium have had lasting and defining effects upon the content of the Christian faith.3 Not the least of these effects is that the written text reigns over all media in the church’s judgment about the value of an expression of faith.

In respect to the medium of pictorial arts, one of the most influential passages in that written word, Exodus 20:4–6, may be and has been interpreted to forbid the iconic arts in the church.4 The Second Commandment was echoed and paraphrased in statements from certain early church theologians.5 Canon 36 of the Synod of Elvira (300–306 CE), which was a local and limited gathering,6 employs the language of Exodus to declare that picturas in ecclesia esse non debere, ne quod colitur et adorabitur in parietibus depingantur (‘There should be no pictures in the church building, lest what is worshipped and adored might be painted on the walls,’ or, ‘. . . lest what is painted on the walls should be worshipped and adored’). Discussions of the so-called aniconic texts from the early church abound in the histories of art.7 With early church pronouncements buttressed by the belief that the Judaism of late antiquity was aniconic and further strengthened by the apparently late appearance of recognizable Christian art objects (from the beginning of the third century, at the earliest), a consensus arose among many historians which stated that it was virtually a miracle that there was any Christian iconic art. Pope Gregory the Great is credited with the rescue of pictorial art for the Western Church. In his letters to the Bishop of Marseilles in 599 and 600 CE (Epistolae, IX, 209; XI, 10) he declared that church decorations are ‘for the instruction of the ignorant, so that they might understand the stories and so learn what occurred.’ Gregory’s pronouncements were not mainly intended to rescue an art form, as Kessler points out; Gregory’s intention was a clever missionary plan.8 In the Eastern Church, the iconographic wars and their aftermath settled the clash between iconic and aniconic voices.

But the existence of a prolific art early in the church’s history, set over against the perceived standpoint of the church’s theologians against such art, creates a dilemma for historiography. The historical question, in the light of seemingly strong resistance to iconic representations in the church (and Judaism), becomes: How does one account for the development of a Christian art? André Grabar puts the dilemma in the form of a challenge:

Whatever the degree of relationship between the two iconographies, Jewish and Christian, may have been, and the causes of the interdependence of their images, the historian of Christian iconography is faced with the question: Why did the two traditionally aniconic religions, which existed side by side within the Empire, equip themselves with a religious art at the same [i.e. the Severan] period?9

The dominant theory in answer to Grabar’s question was that, at least until the ‘baptism’ of pictorial art after Constantine’s triumph (c. 315), Christian art was a folk art which stood over against the wishes of the clergy and other church officials. Christian pictorial art developed ‘from below,’ from the laity. In particular, the art was desired by pagan converts who were used to images in worship, in the face of official doctrinal resistance.10 Sister Charles Murray calls this the ‘classical’ theory of the development of Christian pictorial art.11

The ‘classical’ theory is itself under challenge. The early texts, under scrutiny, turn out to be less condemnatory of all images and more precisely aimed at the idolatrous use of images than the classical hypothesis maintains. In addition, there have been several developments in the history of art which have added weight to these challenges. There has been the discovery of profusely decorated places of worship in both Judaism and Christianity (at Dura Europos and other sites). The art of these early places of worship, as well as that in the catacombs, shows strong evidence that (1) it developed from prolifically illustrated sacred texts, such as copies of the Septuagint,12 and (2) that the existing art (from the beginning of the third century) reveals signs that it had considerable antecedents. Third, a study of the texts of the Judaism of the Imperial Period shows that Judaism was not a consistently aniconic tradition which took a fundamentalist attitude toward the Decalogue, especially in regard to pictorial art.13

It still holds, however, that there is no extant art which can be identified as indisputably Christian before the end of the second century. This fact does not, however, completely rule out the possibility that such art never existed. It is well known in iconographical circles that the Christians borrowed their art forms from the existing art vocabularies available to them in the wider social matrix. There is virtually no Christian iconic symbol in the earliest extant material that does not have a pagan counterpart. Thus, the earliest Christian art is often difficult to distinguish as Christian. The hypothesis of the classical theory mentioned above has become even more difficult to hold with the discovery in the 1950s of the catacomb below the Via Latina in Rome. There, Christian and pagan art mingle in startling fashion, but, more importantly, some of the images at Via Latina, like those of the church and synagogue at Dura Europos, display signs that they had a considerable iconographic tradition behind them.14

The problems accompanying the relatively late appearance of recognizably Christian art can be at least partially solved if we pay attention to estimates of the growth of the numbers of Christians in the Empire. Rodney Stark has provided some very important sociometric data to this point. Stark demonstrates that until about the year 150 CE, Christians would have made up about 0.07 percent of the total population. Between 150 and 250 CE, Christians would have grown to 1.9 percent; from 250 to 350 CE they increased to 10.5 percent in 300 CE and 56.5 percent by 350 CE. Given the generally accepted estimated population of the Roman Empire, that is, about 60 million people, there would have been only about 7,500 Christians in the Empire in the year 100 CE, 40,000 in 150 CE, 1 million in 250 CE, and just over 6 million in 300 CE.15

The population growth of early Christianity was therefore exponential. A curve of our accumulation of pictorial artifacts from the early church would show a similar pattern. The number of such artifacts which we can safely say are Christian is sparse at the end of the second century and through the middle of the third century; the number of these artifacts increases dramatically during the period of the greatest growth in Christian population in the Empire, that is, during the late third and fourth centuries. It should be noted as well that the number of rhetorical artifacts which have come down to us from the early church is also consistent with those of iconic items. With the possible exception of Papyrus Bodmer V (Protevangelium Jacobi), we have only fragments of early Christian writings until the fourth century.16 We assume that many of these fragments are from complete manuscripts of, say, the gospels or the epistles.

There is no doubt that certain elements in both Judaism and Christianity were suspicious of pagan practices and, of course, idolatry was a subject of ardent Christian suspicion. Ernst Kitzinger rejects the ‘classical’ hypothesis’ belief that it was the Second Commandment which delayed the appearance of Christian art and believes that it was the church’s abhorrence of paganism which accounts for the absence of Christian iconic art prior to c. 200 CE.17 The attitude of both the Christian and Jewish traditions toward the development of pictorial art appears actually to be in a distinction they made between the function of art as decoration and for heuristic purposes as opposed to the pagan idolatrous function, that is, the worship of an art-object. The latter was anathema.

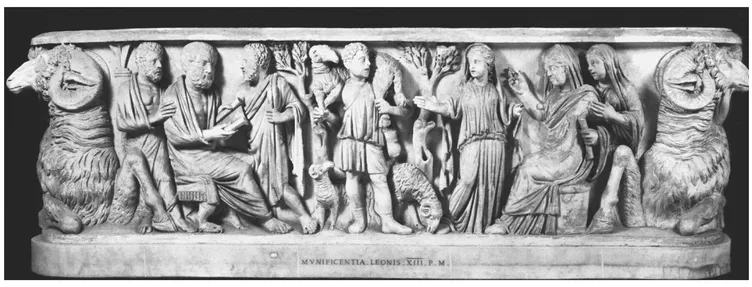

Just when Christians began to use and to create pictorial art is therefore not settled. Both issues fall into the ‘Abominable Snowman’ problem. That is, it is virtually impossible to prove that something does not exist; it is also easy to summon hypotheses to theorize that this something might have existed, whether it did or not. There are a number of images which fall on the cusp between the Christians’ using images which they acquired from pagan culture and their creation of images as ‘their own.’ In his lecture at a symposium connected with the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exhibition, ‘The Age of Spirituality,’ immediately after he insists that Murray is in error in her insistence that Christian art appeared earlier than what she calls the classical theory would allow, Kitzinger gives a brilliant ‘reading’ of one of the sarcophagi [Figure 1.1] in the exhibition to show how this art object is Christian and how Christians would have seen it. Ironically, it is this very sarcophagus which, in the published catalog of the exhibition, Carder employs to show how some very early ‘Christian’ art may or may not be Christian.18

Paul Corby Finney19 has added a fruitful element to the discussion of the ‘begin-ning of Christian art.’ Noting that the first collection of Christian iconic art is in the cemetery of S. Callistus (Callixtus) from which there are funereal decorations (frescoes) which were painted approximately at the end of the second century, he employs the Callistus paintings as a paradigm for the cultural and social development of Christian iconography. It is no accident, says Finney, that this development took place at about the same time as the early Christian apologists were writing. Both were a sign that a hitherto small, poor and loosely organized group, that is, the Christians, began to go public. The paintings in the catacomb, including their decorations (borders, birds, fish, and so on), demonstrate a group who were employing the basic funereal iconography of paganism and beginning to Christianize it. A chief element in this development was the fact that Christians had begun to arrive at a period in their growth when they were (1) organized enough to plan for such a project, and (2) had the economic means to purchase the land and to pay for the excavation and decoration of the cemetery.

Finney also points out that the development of such an iconographic enterprise as the digging and the decoration of S. Callistus does not preclude the employment of pagan personal or household art in Christian homes. Finney employs the well-known Wulff oil lamp (Wulff 1224)20 as his main example. Several of the ‘Shepherd Lamps’ can be acceptably dated in the period of 175–225 CE. It is not only on lamps of the late second and early third centuries that the Good Shepherd appears. We know that Tertullian mentions the use of the image on Christian drinking glasses. Finney, building on studies which have identified an Annius as a major manufacturer of these lamps in the period, concludes:

Thirty years later, on the example of the painted shepherd carrying the oversize sheep in the lunette decoration over the Dura baptismal font, the practice had spread from Rome to the Syrian limes. In Rome, the shepherds carrying their sheep began to appear around 260 in relief sculpture ... commissioned by the new religionists. Last but not least, within the literary culture of the new religionists ... there existed a long-standing exegetical tradition that associated the founder of the movement with shepherding metaphors. Under such circumstances as these, it is reasonable to suppose that at least an occasional Christian customer will have been prompted to purchase one of Annius’ shepherd lamps on the basis of its discus [a roundel on the top of the lamp which contains an image or inscription] subject.21

In short, from evidence such as that presented by both Finney and Stark, we can reasonably assume that there was ‘Christian art,’ that is symbols available and acquired on artifacts from the larger social matrix which Christians interpreted as Christian, before we find iconic representations that can be positively identified as produced by a Christian aesthetic.

Figure 1.1 Teaching scene and orant. Sarcophagus, late third or early fourth century. Museo Pio Cristiano, Vatican. Found in the Via Salaria, near the Mausoleum ofLicinius Paetus. Photograph: Graydon F. Snyder.

The church clearly did overcome whatever reluctance it had toward pictorial art, although in the East it required passage through a bloody war before the issue was settled. One central criticism of pi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Permissions and Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1 Text, Art and the Christian Apocrypha

- 2 Mary

- 3 Images of the Christ

- 4 The Life and Mission of Jesus

- 5 Paul, Thecla and Peter

- 6 Apostles and Evangelists

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of Extracts from Apocryphal Texts

- General Index