![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

This is not just an urban design book, nor is it a social policy book or management guide – in fact it is a bit of all three plus some more. The challenge in creating and maintaining successful public spaces is to achieve an integrated approach, which includes design and management set within the broader context of urban policy. Many books have been written about public space from a design (usually visual) point of view and some books have been written from a policy viewpoint. I have undertaken the rather daunting task of straddling several disciplines, because I feel that only by taking this multifaceted approach will we succeed in producing more convivial spaces. As Ken Worpole, one of the most prolific and perceptive writers about public space, observes: ‘Given the deep social and economic nature of the circumstances that underpin or undermine a vibrant community and public space culture, it is clear that design or architecture alone cannot solve these problems, though in many places there is still a pretence that they can’ (quoted in Gallacher 2005 p11).

Overview

Why, when we have more overall wealth with which to potentially enrich spaces and places for citizens to enjoy have we often produced built environments that are bland or ill-conceived for public use and, in some cases, positively unpleasant?

What kind of public spaces do people prefer to be in? This book aims to tease out what gives some places ‘personality’ and ‘conviviality’, so that we can learn from the past and present to design, maintain and manage better quality built environments in future.

Drawing on theory, research and illustrated case studies, this book identifies the factors that draw people to certain places. In the 1960s and 70s there was considerable published discussion about what differentiates livable urban environments from unpleasant (and subsequently problematic) ones (see for example Jacobs 1961, Cullen 1961, Rapoport 1977). This important debate about the form and nature of successful spaces and places appears to have been superseded by narrower technical discussions about physical sustainability, security, management and aesthetics.

Many studies of the urban fabric (including a number written by this author) start with an analysis of what is wrong, but this book will also look at what is right and see if there are any replicable formulas for successful public spaces and places.

Figure 1 Unconvivial: Dublin docks area redevelopment

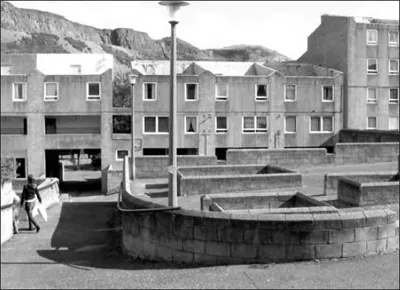

Figure 2 Unconvivial: Causewayside, Edinburgh

Figure 3 Convivial: Freiburg, Southern Germany

Figure 4 Convivial: Camden Lock, London

Discussion

I have spent most of my professional career working in or visiting the most unpopular and degrading parts of towns and cities, in an (often futile) attempt to help them improve. But in my travels to many towns and cities both here and abroad I have also tried to look at the flip side – what it is about some places that makes me feel good in them?

There has been a recent interest in making ‘better public places’, emanating both from the British Government (e.g. through their support for the Commission for Architecture in the Built Environment [CABE]) and the built environment professions (e.g. the Urban Design Group). In America, the drive for better place-making is spearheaded by the New York-based Project for Public Spaces and we now have the European Centre on Public Space driving a similar agenda on this side of the Atlantic. This has led to various guides on ‘place-making’ (e.g. the Good Place Guide and various CABE briefings). But this guidance is based on what professional designers consider a good place. Less research has been undertaken into what ordinary citizens want from their public spaces and what they perceive as good places to be in (i.e. convivial spaces). This book is based on a multidisciplinary understanding of what makes certain public spaces more successful than others and draws on user feedback as well as professional opinion and academic research. I have coined the term ‘convivial spaces’ to describe open, public locations (usually squares or piazzas) where citizens can gather, linger or wander through. In some cases, such as Stroget (the famous ‘walking street’) in Copenhagen, streets and their associated open areas can be convivial spaces. ‘Convivial’ is defined in dictionaries as ‘festive, sociable, jovial and fond of merry-making’, usually referring to people, but it can equally apply to a situation. Famously, Ivan Illich used the term in the title of his seminal work Tools for Conviviality. Places where people can be ‘sociable and festive’ are the essence of urbanity.

Figure 5 Siena, Italy

Without such convivial spaces, cities, towns and villages would be mere accretions of buildings with no deliberate opportunities for casual encounters and positive interactions between friends or strangers. The trouble is that too many urban developments do not include such convivial spaces, or attempts are made to design them in, but fail miserably.

However, convivial public spaces are more than just arenas in which people can have a jolly good time; they are at the heart of democratic living (Carr et al 1992) and are one of the few remaining loci where we can encounter difference and learn to understand and tolerate other people (Worpole and Greenhalgh 1996). Without good urban public spaces, we are likely to drift into an increasingly privatized and polarized society, with all its concomitant problems. Despite some improvements in urban development during the last couple of decades, we still produce many tracts of soulless urban fabric that may deliver the basic functional requirements of shelter, work and leisure but are socially unsustainable and likely generators of future problems.

Figure 6 Brent, North London

There are far too many sterile plazas and windswept corners that are spaces left over from another function (such as traffic circulation or natural lighting requirements for tall buildings). This phenomenon is sometimes referred to as ‘SLOAP’ – space left over after planning. Urban land is at a premium, so in a profit-orientated society, space where people can just loaf around is not seen as a financial priority. Furthermore, contemporary worries about security, litigation and ‘stranger danger’ result in the urban realm becoming increasingly privatized and controlled.

Some town centres (e.g. Dallas, Texas) and suburbs have more or less given up on informal communal spaces altogether, on the presumed basis that they are costly to manage and might attract the wrong kind of person or usage. This privatized retreat has reached its apotheosis in the ‘gated community’ where no one, apart from residents and their approved guests, is allowed to enter. Can such places be genuinely described as ‘civilized’?

In this book I suggest that there is no single blueprint for a convivial space, but there do seem to be some common elements, which may be broadly categorized under the headings of physical (including design and practical issues), geographical (location), managerial, sensual (meaning how a space directly affects one or more of our five senses) and psychological (how the space affects our mind and spirit).

The book is structured to flow from the theoretical and political to the practical. So early sections cover the whys and wherefores of public space before moving on to principles and then some specific proposals and examples.

Defining Convivial Spaces

Francis Tibbalds, in his seminal work Making People-friendly Towns (1992), suggests that such places should consist of ‘a rich, vibrant, mixed-use environment, that does not die at night or at weekends and is visually stimulating and attractive to residents and visitors alike’. John Billingham and Richard Cole, in their Good Place Guide (2002), chose case studies that answered affirmatively to the following questions: ‘Is the place enjoyable – is it safe, human in scale, with a variety of uses? Is it environmentally friendly – sunlit, wind and pollution-free? Is it memorable and identifiable – distinctive? Is it appropriate – does it relate to its context? Is access freely available?’

Given that many convivial places seem to have grown organically through an accumulation of adaptations and additions, can we design such places at the drawing board? Critics of formal architecture and planning such as Bernard Rudofsky (Architecture without Architects [1964]) and Christopher Alexander (The Timeless Way of Building [1979], A Pattern Language [1977]) suggest that we are better off ‘growing’ good places and spaces, rather than trying to build them from a blueprint – this is discussed in ‘Designed or Evolved?’ in Chapter 4 (page 81). There are some ancient and modern examples to suggest that it is possible to design convivial places as a whole, but they tend to be relatively small in scale. The post-1947 culture of master-planning whole urban areas is less likely to accommodate the fine grain, local nuance and adaptability that seem to be at the root of convivial places.

You may disagree with me about the kind of places that are convivial; you may enjoy the buzz of a much more hard-edged, clean and symmetrical environment, such as Canary Wharf (London) or La Défense (Paris). You may even enjoy spending time wandering around the closely supervised and sanitized spaces of out-of-town shopping malls such as Cribbs Causeway near Bristol and Bluewater in Kent; many do, but for what reasons? And why do other people loathe such places? There are many such questions to be answered about the effect of different places on different people.

The rest of this book attempts to unpack the various factors and observations, outlined above, that constitute convivial spaces. By understanding what the ingredients of a successful public space are, we should be able to create more good ones, avoid constructing more bad ones and remedy some of the already existing bad ones. I recognize that good urban design is a crucial factor in all this, but unlike many books on the subject, I also stress the significance of management and geography and how all these objective factors affect our senses and psychology. Ultimately, conviviality is a subjective feeling, underpinned by, but not to be confused with, the actual physical state of a place.

This book is not an exercise in cosy nostalgia. Examples will be given of comparatively recent ‘unplanned’ places that have considerable ‘personality’ and recent developments or redevelopments that have transcended the sterility of many modern built environments. Although arguing for a more huma...