This is a test

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Preface to Hopkins

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

An authoritative guide to the life and works of Hopkins, for those who require a good introduction from which to explore the author's works more fully.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Preface to Hopkins by Graham Storey in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

The Poet in his Setting

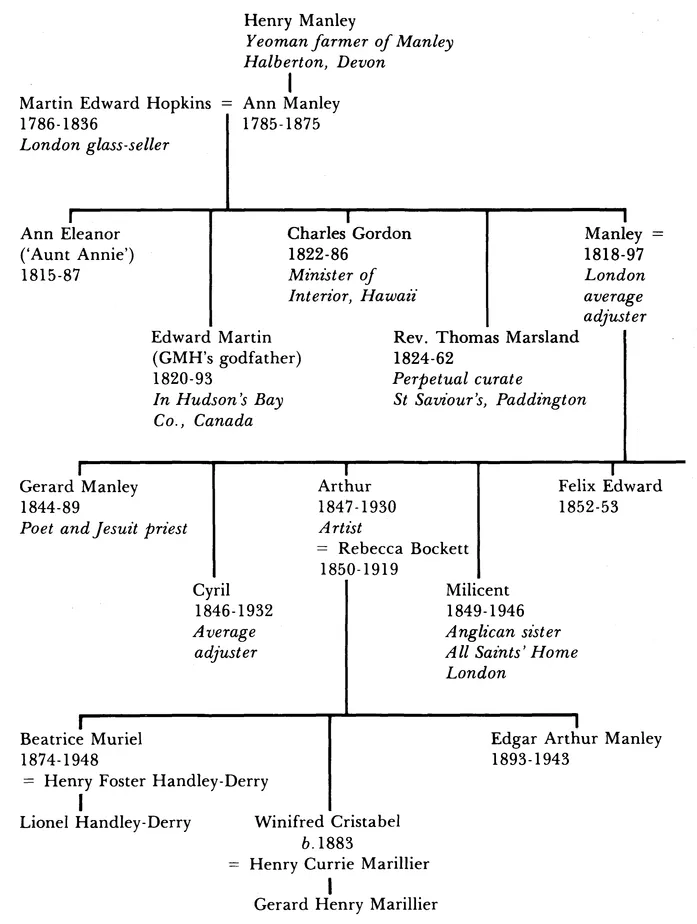

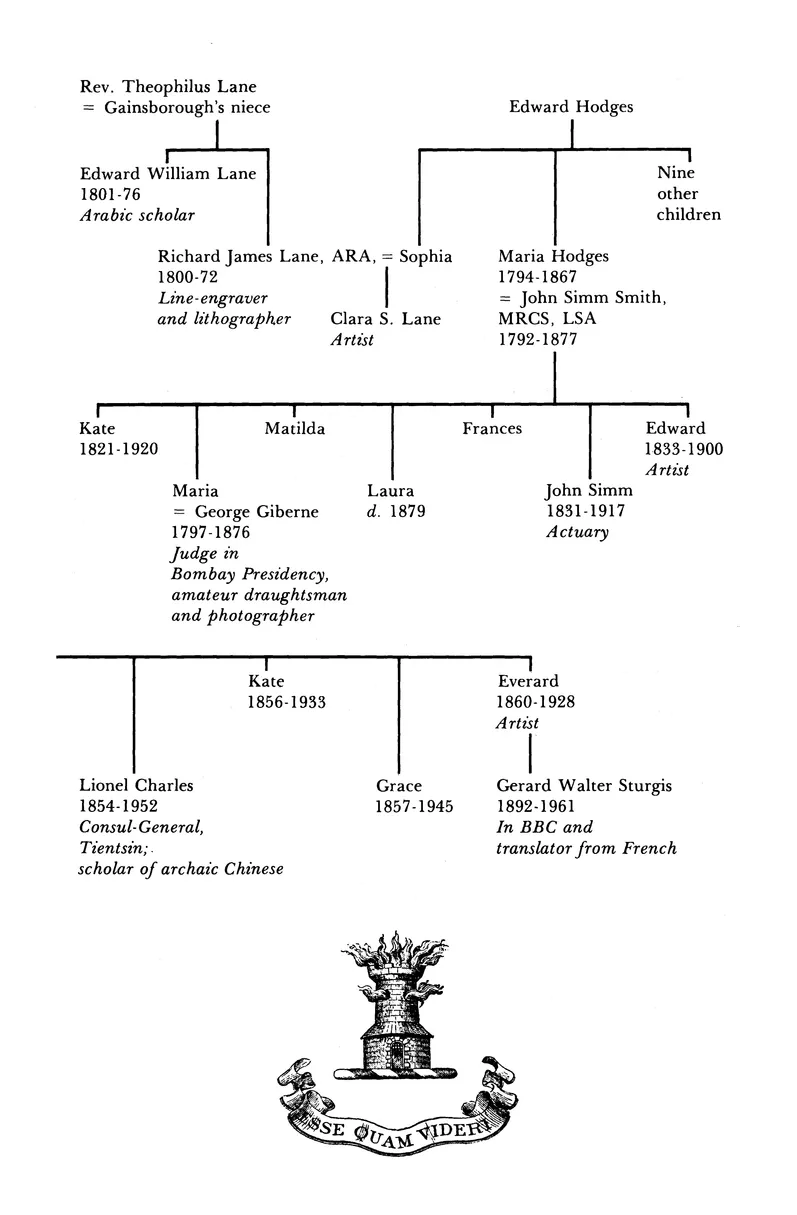

The Hopkins and Smith families

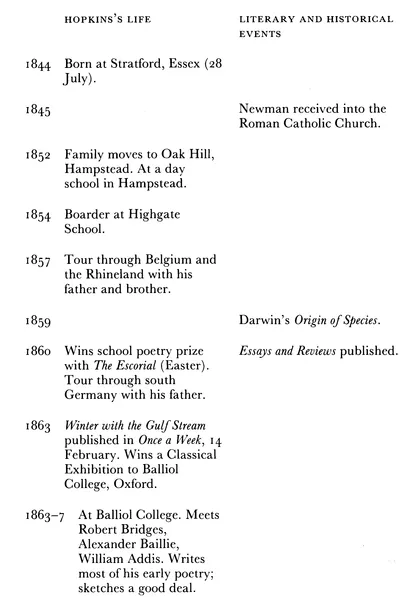

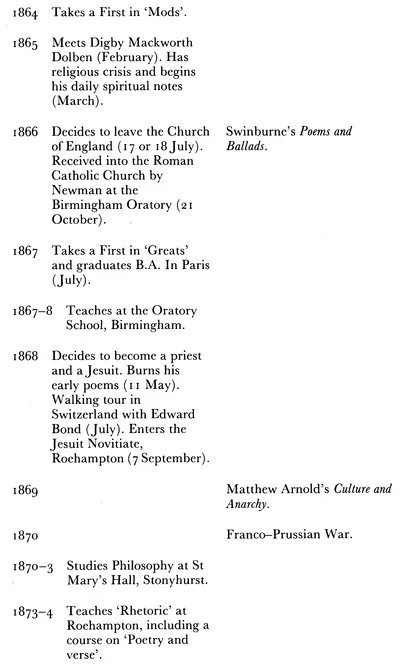

Chronological table

1 Hopkins's life

Family background and school

The Hopkins family was prosperous, cultivated and, on both sides, had connections with the fine arts. Hopkins's great-uncle on his mother's side, Richard Lane, was Gainsborough's great-nephew and himself a distinguished line-engraver and lithographer who exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy. His uncle, again on his mother's side, Edward Smith, was a professional watercolour painter. Two of his father's brothers married granddaughters of the portrait painter, Sir William Beechey; and one of them, Frances Ann Hopkins, whose husband was in the Hudson Bay Company, became well known in Canada as a painter of voyageurs, the canoemen in the fur trade. Other relations were minor artists.

When Gerard was born, on 28 July 1844, the eldest of three sisters and five brothers, his parents, who had married a year before, were living in Stratford, Essex. His father, Manley Hopkins, was clearly something of a dilettante, but achieved a fair measure of success in his remarkably diverse interests. He ran his own marine insurance firm in the City; was Consul-General for Hawaii in London for forty years; and published a variety of books, including three volumes of verse. The Hawaiian connection must have brought an unexpectedly exotic element into the Hopkins home.

Gerard's mother, Catherine Hopkins (nee Simm Smith), was the daughter of a successful London doctor. She greatly valued her son's poems and lived to see them published in 1918, when she was ninety-seven. Soon after Gerard's birth, her father moved from London to Blunt House, Croydon, a large house in what was then the country. Gerard certainly spent periods of his boyhood there (his younger brother Lionel described it as 'a second home'); and an early drawing, done when he was eighteen, is of weeds ('Dandelion, Hemlock and Ivy') in one of its fields.

As in so many Victonan homes, an unmarried aunt lived with the family and played a large part in educating the children: Manley's sister Ann Eleanor Hopkins, 'Aunt Annie', a talented amateur painter, who encouraged Gerard's early drawing and music. In 1864 he described her in a letter as 'deep in archaeology etc. etc.'. She clearly fostered similar talents in some of the other children too. Two of Gerard's brothers, Arthur and Everard,

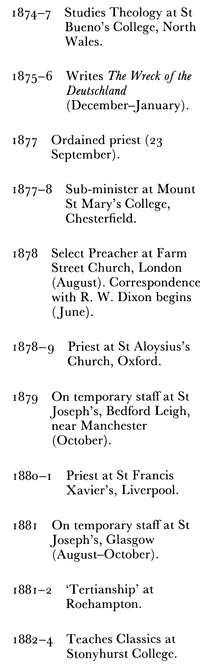

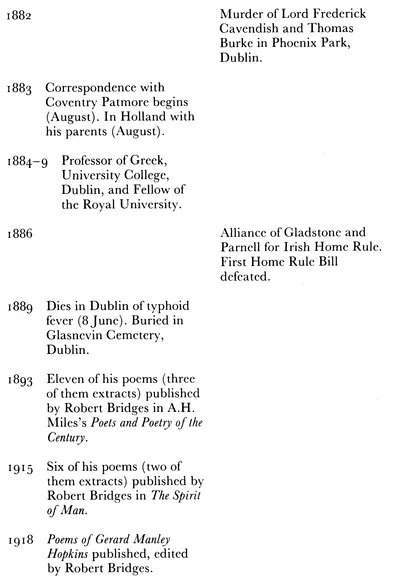

Hopkins, aged 14½, by Ann Eleanor Hopkins

Hopkins's, father, Manley Hopkins, October 1876

Hopkins's mother, Catherine Hopkins

became well-known artists and illustrators; and one sister, Katie, had a marked gift for drawing. Several of Arthur's sketchbook drawings, reproduced in All My Eyes See: the visual world of G.M. Hopkins, show a strong affinity with Gerard's early sketches. Another sister, Grace, was an accomplished musician and later set accompaniments to Gerard's melodies for poems by Bridges and R.W. Dixon. His eldest sister, Milicent, became an Anglican nun. Perhaps the most interesting of Gerard's brothers, for the way in which he used his linguistic talents quite differently to Gerard's, was the youngest, Lionel, who, after a career in the British Consular Service in China, retired early and became a scholar of worldwide reputation of the Chinese language. The last survivor of the family, he died in 1952, aged ninety-seven. He greatly admired Gerard, and the one letter from Gerard to him that has survived shows the philological interests they had in common.

The Hopkins family was clearly a closely-knit and affectionate one, with strongly shared interests in poetry, painting, music and word play. It is disappointing that no letter or comments which might have illuminated Gerard's relations with his mother and father, or with any of his brothers and sisters, seems to have survived before he went up to Oxford.

In 1852 the family moved to Oak Hill, Hampstead, where they stayed for thirty-four years. For two years, Gerard went to a day school in Hampstead. Then in September 1854 he moved to Highgate School (originally Sir Roger Cholmcley's Grammar School, by then a small public school). For most of his eight years there he was a day boy, then finally a boarder in Elgin House. His headmaster was the Rev. John Bradley Dyne, D.D., former Dean of Wadham College, Oxford: a good teacher of the Classics (the study of which, according to Edmund Yates, who was at Highgate a few years before Gerard, he considered 'the primary object of our creation'); but, as a headmaster, heavy-handed and tyrannical (the 'Patriarch of the Old Dispensation' Gerard called him). It was probably inevitable that a boy as intellectually precocious, sensitive and sharply individual as Gerard should clash with such a man particularly if he felt a sense of injustice. But a letter he wrote in his final year to his friend Charles Luxmoore, who had just left, reads amazingly - even for 1862: 'Dyne and I had a terrific altercation. I was driven out of patience and cheeked him wildly, and he blazed into me with his riding-whip.' After 'a worse row' in which his covictim 'was flogged, struck off the confirmation list and fined £I', Gerard was 'deprived of [his] room for ever, sent to bed at half past nine till further orders, and ordered to work only in the school room, not even in the school library'. After a final misdemeanour, 'Dyne . . . sent me to bed at nine and for the third time this qriarter threatened expulsion, deprivation'. This harsh treatment seems all the stranger when we read the impressions of Gerard by his younger brother Cyril, who followed him to Highgate and later compared him to the young Swinburne:

There is a passage in Lord Redesdale's Memoirs relating to the school-days of Swinburne, so suitable to those of my brother Gerard that I cannot resist quoting it: 'Of games he took no heed — they were not for his frail build; football and cricket were nothing to him. And so he led a sort of charmed life, dreaming and reading, and chewing the cud of his gleanings from the world-harvest of poetry, a fairy child in the midst of a commonplace, workaday world.' And like Swinburne, he was not deficient either in moral or in physical courage, for he was a fearless climber of trees, and would go up very high in the lofty elm tree, standing in our garden ... to the alarm of onlookers like myself.

Any resemblance to Swinburne ends there. In the Poetry Review, 1942, Lancelot de Giberne Sieveking told stories of Gerard's visits to the Giberne family home at Epsom as a boy: of his intent listening to bird song, and his 'arranging stones and twigs in rows and patterns, with infinite care' (anticipating an old lay brother's memories of him at Stonyhurst in 1882, recorded by Denis Meadows in 1913: 'Ay, a strange young man, crouching down that gate to stare at some wet sand. A fair natural 'e seemed to us, that Mr 'opkins.') Mr Sieveking's stories came from his mother, Gerard's cousin; his grandfather was Gerard's uncle, George Giberne, retired Chief Judge of the East India Company, and a very early photographer.

Despite his rows with the headmaster, Gerard had an exemplary school career. He won several prizes for Classics, a gold medal for Latin verse, a school scholarship, and in 1863 an Exhibition to Balliol College, Oxford. By then he had also won a school prize for his poem, The Escorial, written when he was only fifteen; and also written A Vision of the Mermaids (illustrated with a pen-and-ink drawing), and Winter with the Gulf Stream. This was published in Once a Week, on 14 February 1863, when he was eighteen — almost his only poem to be published in his lifetime. And whatever his relations with the headmaster, he was popular with his schoolfellows. They found him likable if eccentric; but both sensitive and strong-willed to an unusual degree. The poet R.W. Dixon, who spent a few months in 1861 as a master at Highgate and later became a friend and important correspondent of Gerard's, wrote to him in 1878 that he remembered him clearly as 'a pale young boy, very light and active, with a very meditative and intellectual face'. His appearance, and his nickname of'Skin', probably belied the strength of his will, already exercised on one occasion at least on self-denial. Both his brother Cyril and Charles Luxmoore tell the story of how, for a bet — the real reason being 'a conversation on seamen's sufferings and human powers of endurance' - he abstained from all liquids for a week (Luxmoore says, impossibly, for three weeks). Gerard won the bet, but collapsed at drill with a blackened tongue, and was immediately punished by Dyne.

One of his closer school friends was Ernest Hartley Coleridge, grandson of the poet, with whom, in one long letter, Gerard discusses Theocritus, Aeschylus and Tennyson, and sends long fragments of three more of his own poems. Another was Marcus Clarke (the 'co-victim' above), who achieved some fame as a writer in Australia, particularly with his convict novel For the Term of his Natural Life. Clarke greatly admired Gerard, putting him into at least two of his stories; in return, Clarke was a recipient of Gerard's early fascination with words: 'Marcus Scrivener,' he called him, 'a kaleidoscopic, parti-coloured, harlequinesque, thaumotropic being.'

This sense of fun was one of the things that Charles Luxmoore most remembered in him: 'He was full of fun, rippling over with jokes, and chaff, facile with pencil and pen, with rhyming jibe or cartoon.' It comes out strongly in some of the charming, lighthearted drawings of his schooldays that have survived. It alternates too with one brief reference showing the seriousness with which he treated his friendships (and the pain they could cause him), which he quotes to Luxmoore from a Journal he kept for 1862 (parts of which he later burnt).

But his drawing was much more than fun. G.F. Lahey, S.J., writing about Gerard's boyhood, no doubt had evidence to state that, had Gerard not decided to become a Catholic priest, 'he would undoubtedly have adopted painting for his profession, as a future drawing-master strongly advised him to do'. (G.M. Hopkins, 1930, p. 2). After his first year at Oxford, Gerard wrote to his undergraduate friend Alexander Baillie: 'I have now a more rational hope than before of doing something — in poetry and painting . . . about the latter ... I have great things to tell.' And, after he had decided to take orders, four years later, he wrote to Baillie again: 'You know I once wanted to be a painter.'

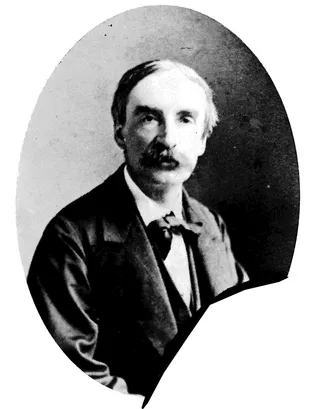

Gerard made two early visits to the Continent with his father: to Belgium and the Rhineland when he was thirteen, and to southern Germany at sixteen. From Nuremberg, says Lahey, he enclosed 'some first-rate sketches of Bavarian peasantry'. His surviving drawings date from 1862, two years later; the most impressive of them a group of seven pencil sketches done on a family holiday in the Isle of Wight in July-August 1863 (his first long vacation from Oxford). They are of rocks, waves, clouds, trees and — perhaps the best known - an iris; apart from their merit as remarkably fresh and beautifully observed drawings, they have a particular interest: for in their intense apprehension of nature they clearly anticipate the 'inscapes' (his own later coined word for a thing's distinctive, inner form) that both his Journal (kept from 1866 to 1875) and, ultimately, his mature poems aimed to express. More drawings illustrate his Journal - the most ambitious ones done on a Swiss tour of 1868, a few months before he entered the Jesuit novitiate. And many years later, in 1884, he wrote to his sister Kate, regretting that he had given up his drawing:

Shanklin, Isle of Wight. Sketch by Hopkins.

A dear old French Father . . . finding that once I used to draw, got me to bring him the few remains I still have, cows and horses in chalk done in Wales too long ago to think of, and admired them to that degree that he is urgent with me to go on drawing at all hazards; but I do not see how that could be now, so late: if anybody had said the same 10 years ago it might have been different.

Hopkins's last two terms at school witness a new excitement in writing. 'I have been writing numbers of descriptions of sunrises, sunsets, sunlight in the trees, flowers, windy skies etc. etc.', he told E.H. Coleridge, in a letter sending him three long fragments of poems.

I have begun the story of the Corinthian capital; of course you know it; I think we spoke of it before. I have done two thirds of 'Linnington Water, an Idyll', and am planning 'Fause Joan' a ballad in the old style. All these things are done in scraps of time.

His love of the Classics remained, indeed grew stronger. But he had clearly outgrown Highgate and its restrictions. 'The truth is I had no love for my schooldays and wished to banish the remembrance of them', he wrote years later to his friend Canon Dixon. Oxford was to be very different. He went up to Balliol College to read Classics in April 1863 and thrived from the start. 'Not to love my University would be to undo the very buttons of my being', he wrote to Baillie seventeen years later.

Oxford

The Balliol that Hopkins went up to in April 1863 was a small college of fewer than a hundred undergraduates, but a very distinguished one. After a long period of intellectual lethargy that had afflicted most of Oxford, Balliol had been one of the first colleges in the 1830s to reform itself, to set high standards of scholarship and intellectual enquiry and, above all, of dedicated teaching. Most of the undergraduates, like Hopkins himself, read Classics - Literae Humaniores ('Greats'), as the Honours school is called at Oxford Greek and Latin language and literature, ancient history and philosophy; and, academically, the 1860s were probably Balliol's most impressive decade. In the four years that Hopkins was up, Balliol men gained nearly a quarter of the first class degrees in Classics awarded throughout the University. Hopkins shared in this impressive achievement by taking firsts himself, as he was expected to, in both Honour 'Mods' (in 1864) and 'Greats' (in 1866).

Academic success was rated highly in Balliol and Hopkins's diaries and letters are full of delight at his friends' achievements and commiseration for the 'disasters'. He was intensely proud of his college. 'He is the cleverest man in Balliol, that is in the University, or in the University, that is in Balliol, whichever you like', he wrote to his mother about one contemporary. But Balliol was also the centre of advanced thought at Oxford, and of the religious controversy that went with it. Both were identified to an unusual degree with Benjamin Jowett, a Fellow since 1838 and far and away the most influential of the Tutors. Jowett was a legendary figure long before he became Master of Balliol in 1870; and both his supporters and detractors are agreed on the remarkable influence that he exerted. The aim he set himself as a teacher was the Socratic one: to reach the truth by questioning; to clarify, not to impart ideas; to encourage his pupils to use their own minds. He was totally dedicated and immensely hard-working: besides his college lectures and tutorials, he lectured, as University Professor of Greek (at a salary of £40 a year), on Plato's Republic: the beginning of his great translation of Plato that made him famous. Hopkins was never a 'Jowett-worshipper', as Jowett's inner circle of pupils were called, but it is clear that he came under his spell. According to Hopkins's friend Martin Geldart, a Balliol contemporary, it was Jowett's 'purity' which struck Hopkins: 'what had he been but a Catholic, he would have called his "saintliness"' (A Son of Belial, 1882, Geldart's thinly disguised autobiography). This is the more striking, since tutor and pupil stood at opposite ends of the religious spectrum: Jowett, the acknowledged leader of the Oxford Broad Church party; Hopkins, a devout Anglo-Catholic ('my Ritualistic friend', Geldart calls him in A Son of Belial). Hopkins wrote essays for Jowett and was advised to take great pains with them; was embarrassed by his famous silences, but, when he could get him to talk, found him 'amusing'. Jowett, according to Jesuit sources, said later that he 'never met a more promising pupil'; Fr Lahey, Hopkins's first biographer, says that Jowett called Hopkins 'the star of Balliol'.

His other Balliol tutors and their lectures Hopkins sums up succinctly in his first letter to his mother:

Among the other tutors are Riddell ... he lectures on Aeschylus and Homer; he and his lectures...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- FOREWORD

- Dedication

- INTRODUCTION

- PART ONE: THE POET IN HIS SETTING

- PART TWO: CRITICAL SURVEY

- PART THREE: REFERENCE SECTION

- INDEX