![]()

Part 1

FROM THE BEGINNING

![]()

1

Sustainability – Clues for Positive

Societal and Ecosystem Change

Defining Sustainability

Sustainable practices are best understood after sustainability is defined accurately. Such a definition makes transparent the human goals and values that are integral to the term. However, defining sustainability has been challenging because of the need to include social, economic and environmental factors simultaneously. A narrowly written definition of sustainability will not be consistently interpreted in the same manner by everyone and will vary depending on the readers’ backgrounds. One definition cannot and should not encompass the complexity and capture the nuances that are inherent in the word ‘sustainable’. For example, the Eskimos have at least seven distinct root words for snow. Each root word describes some attribute of snow that is not revealed or communicated when one is limited to using one word. This does not mean that there is no value in this word.

The need to define sustainability broadly and the general overuse of the word ‘sustainability’, has made the most acceptable definition the one espoused in the Brundland Report, that is, ‘management and conservation of the natural resource base and … attainment and continued satisfaction of human needs for the present and future generations’ (WCED, 1987). This definition continues to be valuable for decision makers because it identifies the overarching goals that need to be included in a sustainability assessment. This is why the same definition still needs to be espoused. The 2002 World Summit on Sustainable Development held in Johannesburg, South Africa, used similar terms when asking participating countries to ‘ensure a balance between economic development, social development and environmental protections as interdependent and mutually reinforcing pillars of sustainable development’ (UN, 2002).

These broad definitions require tools to ensure a balance between economic development, social development and environmental protection. Well-worded definitions provide the overarching goals wanted by society, but they are difficult to measure. This book will explore how to measure sustainability, because it has implications for how society develops both its human and its resource capitals.

Why Sustainability Needs to be Unpacked

Because we have defined sustainability, this does not automatically mean that we understand how to implement practices to achieve its goals, nor does a definition provide a ‘roadmap’ to show us how to pursue sustainable practices. Today, there is a need to ‘decode or unpack sustainability’ so that both societies and environments can retain their resiliency and still allow the development of the world's human capital while continuing to consume the globe's resources; we cannot always count on luck to survive (Hsu, 1986). Because of population growth and the lack of uninhabited regions in the world, individual human decisions have a greater impact today than in the past. Societal decisions on what resources to consume cannot be a ‘cosmetic’ fix because of the potential for extensive negative repercussions from unsuitable decisions. Today, decisions can increase the vulnerability of humans and ecosystems to future disturbances (e.g. climate change). In addition, when ecosystems are degraded, they are less capable of providing resources in a sustainable manner.

The emergence of several rapidly industrializing and growing-economy countries is also forcing us to decode sustainability to provide a ‘roadmap’ for them. The historical approaches to industrialization followed by the current highly industrialized countries will not work in today's world. History has shown us how some advancing-economy countries reached their present status by confiscating and consuming resources owned by others. Such an approach will be less successful today because of instantaneous worldwide communications, possible media exposure and, in some respects, a more global economy. Sustainable practices need to be adapted for today's reality. These emerging-economy countries will be making many critical choices for their people; these should be based on how their societies can remain adaptive and develop both their human and resource capital, in the face of climate change.

We cannot continue to compete for ownership of the few new frontiers that sporadically become available. The global communities’ response to claiming new mineral deposits in the Arctic is a classic case of ‘modern-day colonization’. In 2008, the melting of the ice sheets in the Arctic exposed minerals that are now more accessible because of today's technology. The magnitude of these rich mineral deposits is driving a new period of colonization and only time will tell how it ends and who will own it.

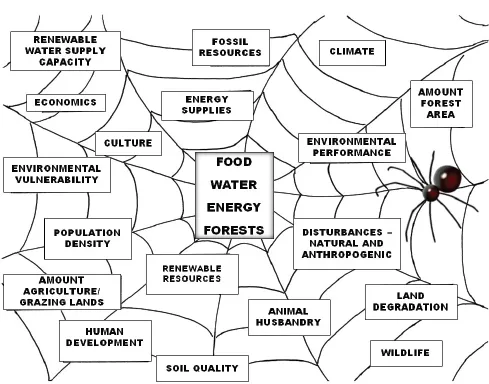

Another part of the problem in decoding sustainability is the need ‘to think and function like an ecosystem’; that is, to include social, ecological and economic factors with all their interconnections and possible feedbacks into one story. Many factors need to be included that may not, at first glance, appear to be relevant to writing the resource–sustainability story. Interestingly enough, sustainability is a complex endeavour that requires the assessor to think like ‘a spider spinning a web’ (see Figure 1.1). Each strand of our web relates to one of the many factors that influence one resource. Webs are not ‘linear’, and a resource is not influenced by only one factor. The successful development of a sustainability web needs to include so many factors that sometimes the primary result of its investigation causes ‘analysis paralysis’. In this state, the assessor gets lost in trying to analyse the volumes of data and forgets what the original goals or questions may have been.

Figure 1.1 The Sustainability Web: A conceptual figure representing some of the

factors affecting human consumption of energy, food, forest materials and water

Centre box = Essential survival needs; Satellite boxes = modifiers impacting these essential survival needs

Ecosystem thinking is a relatively recent idea and one where the principles are still being developed. It began in the early 1960s when ecologists recognized that environments needed to include all the parts of the ecosystem, from the microbes to larger animals and the plants (Vogt et al, 1997). It was not until the early 1990s that social ecologists and ecosystem managers recognized that humans were part of this ecosystem and could positively or negatively impact the sustainability of natural environments. Trying to link the ecosystem and humans at a landscape level has been difficult because of the need to develop mechanistic explanations that link the actions of people with their impacts on the environment. Without such an understanding, it is almost impossible to identify the indicators that can be used to measure the efficacy of past decisions in order to improve future decision making. A lack of understanding of the repercussions and links between protecting and managing forests and people's behaviour when they are denied access to resources continues to be a problem for society. Perla and Vogt characterize how environmental degradation and loss of social resilience is a possible outcome when not all stakeholder values are included when deciding to convert a managed forest into a park (Box 1.1).

Because social and environmental problems are complex and ecosystems-based, making sustainable decisions is not easy and may require difficult trade-offs to be made. We began writing this book because of our recognition that ecosystem thinking is not the norm for managing natural resources and the challenge is to recognize what practice or policy is not sustainable for either humans or an ecosystem.

Box 1.1 Social and Environmental Resilience in the

Skagit Watershed, Washington State, USA

Bianca S. Perla and Kristiina A. Vogt

When wilderness protection designation was given to the Skagit Watershed in north-western Washington, it impacted and altered the social and environmental resilience of people living in the upper and lower reaches of this watershed. Social and environmental resilience was impacted by resources, diversity, memory and connection; these factors varied with watershed location. Understanding how these factors were expressed in upper and lower portions of the watershed can be used to increase the efficacy of conservation when protected areas are established. The social and ecological landscapes that surround protected areas need to be managed if the system's resilience is a goal.

The upper Skagit Watershed, with 43 per cent forest cover, exhibits a short growing season, higher average elevations, steep slopes and poor soils, with limited job opportunities. In contrast, the lower watershed, with 8 per cent forest cover, has longer growing seasons and flat, rich, alluvial plains conducive to both farming and other industries. Lower watershed areas have consistently exhibited higher social resilience values than upper watershed areas (e.g. 9.6 per cent below poverty versus 12.7 per cent); conversely the latter has shown higher ecological resilience. In the 1960s and again in the 1980s, there was a level of community breakdown in the upper watershed as people left or started commuting downriver for jobs; these changes were associated with the designation of the protected area, decline in timber industry, closing of a cement plant and completion of the hydropower dam. Compared to downriver residents, more vulnerable upriver residents perceived more costs and fewer benefits from having a protected area designation in their landscape. The lower watershed has exhibited higher population retention rates; these residents also have higher incomes and education levels. Residents of the lower watershed have 1.7 different jobs over their lifetimes, while the average is 3.4 different jobs for the upper watershed areas.

When protected areas occur in resilient social systems, desirable consequences result; they translate into environmental benefits as well. Relationships between parks and neighbouring areas are an evolutionary process, rather than a one-time effort. Exploration of social and environmental resilience in the Skagit watershed shows that maintaining social resilience is essential to maintaining environmental resilience. This means that effective protected area managers must become increasingly responsible for understanding and promoting social resilience of park borderlands. In short, any type of conservation mandate cannot be successful if it exceeds the ability of social systems to absorb the changes imposed on them. Unstable social systems deteriorate natural systems in the long run.

In an attempt to understand the complex factors impacting human acquisition of basic survival needs, researchers have compiled many stories on resource production and consumption by different societies. It is expensive and time-consuming to collect the data needed to write these stories. They are invaluable to make sustainable decisions for the actual location where they were originally developed; however, they may be totally inappropriate for a neighbouring land. In addition, resource stories are sparse that meticulously document the ecosystem interconnections and possible feedbacks across multiple temporal and spatial scales.

Humans are especially fascinated by stories of societies that collapsed. The success of Jared Diamond's book Collapse (Diamond, 2005) attests to this interest. These stories about the collapse of past societies are interesting to read, but today it is more important to read stories about how and why societies did not ‘collapse’. Societies that did not ‘collapse’ have done something right and their stories may provide us with a greater understanding of what factors are required to be sustainable. Unfortunately, the examples of societies that collapsed will not enable us to make adequately informed decisions so that we can avoid a similar fate, for these stories may simply illustrate a unique condition that does not pertain or is not applicable, to any other situation or area in the world. However, it is clear that most of these examples are linked to over-exploitation of a natural resource that reduced a society's capacity to survive on its own lands. For example, it is clear that during a 4,000-year period the usefulness and economic opportunities provided by Lebanon's cedar trees drove their over-exploitation. Many fierce battles were fought over the ownership of these resources. Loss of these cedar forests triggered the erosion and leaching of salt-rich sediments into the lowland agricultural areas. These sediments reduced agricultural productivity by more than one-half and decreased the capacity of these soils to feed the people dependent upon them (Jacobsen and Adams, 1958; Hillel, 1991). This general statement of over-exploitation as the cause of collapse is further confounded by the fact that several of these societies had survived for hundreds of years and were highly developed until climate change, typically, severe droughts, pushed them towards being unsustainable (Fagan, 2008).

If we look beyond the over-exploitation of a resource as the simple answer as to why a society collapsed, then we shall have a greater chance of making choices that are sustainable. Over-exploitation is only one of the many diverse factors that impinge on whether a choice is sustainable. There is a need to be able to identify why some societies collapsed while others flourished under what initially appear to have been similar ecosystem conditions. There is a need to understand the ‘connections’ between decisions made regarding the use of both human or natural resources and the increased societal vulnerability to their environments. These connections are not always obvious because ecosystems are complex and the repercussions of decisions may be spatially and temporally displaced from the decision itself. Also, most tools available today do not have the ability to integrate the various dynamics of the water, food, energy and forest resources needed by humans to survive.

Decoding Our Current Perceptions of Sustainability

and Is There a Right Model?

History would suggest that humans have not been very capable of living within their social, environmental and economic footprints; this means that we do not have acceptable models that can be used to learn what works, to increase the possibility that a country will make sustainable choices. Traditionally, the expansion of the human footprint has been driven by the economic development activities of industrializing countries. However, several emerging and growing economies are rapidly expanding their resource footprints while pursuing opportunities to participate in the current industrialization visions made possible by carbon compounds. We contend that part of the problem of humans not living within their footprint is that humans address each problem individually and not as a linked set of problems, where a decision made for one problem will have repercussions on another human or environmental problem. Our societal approach to deal with complex environmental and social problems is typically a disciplinary-based approach and is symbolically addressed by using a bandage to control a symptom and not the disease. This means that a bandage solution to a complex environmental problem does not make the ...