This is a test

- 344 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Neuropsychology of Face Perception and Facial Expression

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is the first to offer an overview of the increasingly studied field of face perception.

Experimental and pathological dissociation methods are used to understand both the precise cognitive mechanisms and the cerebral functions involved in face perception.

Three main areas of investigation are discussed:

- face processing after brain damage;

- lateral differences for face processing in normals;

- neuropsychological studies on facial expressions.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Neuropsychology of Face Perception and Facial Expression by Raymond Bruyer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psicologia & Storia e teoria della psicologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | Introduction: Processes Underlying Face Recognition |

Hadyn D. Ellis

It was no accident that the first postage stamps, introduced in 1840, bore the features of Queen Victoria. This facial pattern was chosen in preference to others, partly at least, in order to reduce the risk of forgery: small changes in detail to a familiar face, it was assumed, would be readily noticed and thereby the counterfeiter would be foiled (Rose, 1980). Benjamin Che verton, whose design was accepted wrote, “Now it so happens that the eye being used to the perception of differences in the features of the face, the detection of any deviation in the forgery would be more easy … although (the observer) may be unable to point out where the differences lie.”

The assumption of the early postage stamp designers was that our ability to discriminate and retain facial information probably represents the acme of nonverbal perceptual skills. Indeed, not only can we distinguish among an infinity of faces, but we seem to be relatively good at recognizing large numbers of strangers’ faces following just a brief exposure to them. Moreover, familiar faces can be identified reliably from quite small fragments or under fairly poor viewing conditions (Ellis, 1981). It is difficult to ascertain just how many faces we can store together with other information about the person, but preliminary work by a group of my students indicated that on average we are able to name around 700 people who are known personally. The number of faces we can recognize, however, must double, triple, or even quadruple that figure—a “vocabulary” of faces that is, admittedly small compared with that which exists for words but which is nonetheless impressive.

The primary object of this chapter is to examine the likely stages involved in and leading up to final facial recognition. The ways in which these stages may be interconnected also are explored in an attempt both to review relevant, particularly recent, literature and to see how well these various studies can be integrated within an information-processing framework.

INTRODUCTION

Research into the processes underlying face perception and memory for individuals has accumulated at a very rapid pace during the last 2 decades. Work published before the mid 1970s was largely atheoretical and, although nonetheless of interest to cognitive and social psychologists, lacked any cogent explanatory ideas that might have guided research toward an understanding of the mechanisms underlying physiognomic processing (Bruce, 1979; Ellis, 1975).

Since then there have been a number of attempts at establishing the likely cognitive stages involved in identifying people by their faces (Baddeley, 1982; Bruce, 1979, 1983; Ellis, 1981, 1983; Hay & Young, 1982). The various models that have been advanced usually involve the implicit assumption that these stages are functionally modular and that they are largely independent of one another. This assumption seems warranted in the light of evidence that I review shortly and is one that has been considered essential in other areas of cognitive psychology (Fodor, 1983; Morton, 1981).

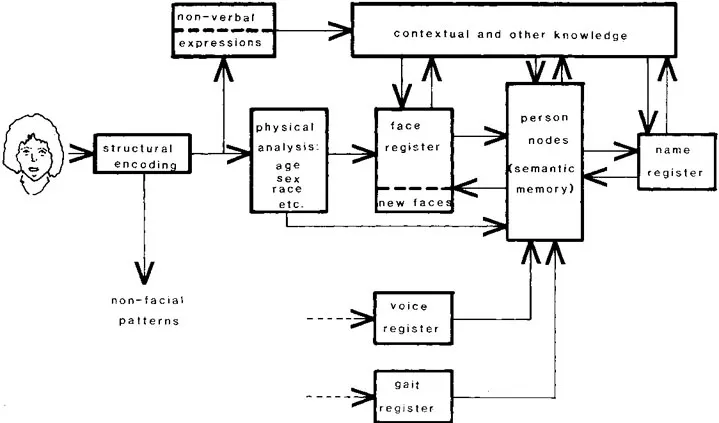

In order both to structure the present chapter and to focus attention upon specific modules preceding facial identification I have constructed the model shown in Fig. 1.1. This model is a hybrid of those already in existence and is offered as a heuristic rather than a definitive explanation. The emphasis of this chapter is on cognitive psychological research but, because much of the evidence for the particular model arises from the neuropsychological literature, it would be inadvisable if not impossible not to make some references to clinical cases of prosopagnosia. (These are considered at greater length in Damasio and Damasio and Tiberghien and Clerc’s chapters). The literature on brain-damaged patients provides evidence about face processing from cases where part of the system is impaired and, as such, offers some of the strongest evidence for functional modularity. The cognitive literature, on the other hand, tends to dwell on experimental evidence concerning the speed and accuracy of face processing and retention under various viewing and post-viewing conditions. Recently, however, Young, Hay, and A. Ellis (1985) showed that investigations of normal, everyday errors in face recognition can provide quite powerful information from which inferences concerning likely mechanisms underlying face processing may be drawn.

Inasmuch as I refer to the Young et al. findings throughout the chapter some indication of the nature of their investigation is appropriate here. They asked 22 people to keep a record of any difficulties or errors they experienced over a 7- week period in recognizing people. From the 1, 000 or so incidents recorded, Young et al. identified seven main categories of commonly occurring slips in person recognition, details of which are cited at appropriate points in the following text.

FIG. 1.1. An information processing model of fact recognition that is used to structure the literature review contained in this introductory chapter.

The model shown in Fig. 1.1, although complicated enough for present purposes, is undoubtedly an oversimplification: it depicts excitatory pathways only, ignoring likely inhibitory ones; and the connections that are shown give only a hint of the likelihood that some subprocesses proceed in a serial fashion whereas others operate in parallel. Furthermore, the system is shown as being vertical rather than horizontal (Fodor, 1983). No account of possible sharing of processing modules with other classes of stimuli has been shown but such cooperation cannot be excluded at this stage. Finally, the model indicates no exit points, but, of course, any processing system must have an output. In the present case it is possible that an output leading to conscious representation could occur at any point in the system but that normally our awareness is confined to the final state of knowing who a person is. Only under unusual conditions or in specific cases of brain damage, are we conscious merely of seeing a face, a female face or a familiar face that cannot be specified further.

There are two principal areas to the model, roughly involving early perceptual processes and later memory processes. Within each area there are a number of subprocesses each of which is considered separately.

Metaprocesses involving extra-facial factors such as environmental context and expectations are also important attributes of an overall face-processing system and these are also reviewed.

PERCEPTUAL PROCESSES

Although any sharp division between perception and memory is a gross oversimplification, it is certainly convenient to discuss them apart. Under the perception rubric I briefly describe putative modules for structural encoding; gross physical categorization; and detection of emotional expression.

Structural Encoding

The initial categorization of a visual pattern as being that of a face is a necessary preliminary stage to the rich processing capacity of what might be termed the general face schema. It is probably based upon an automatic analysis in which the essential “facedness” of the stimulus input—or the recognition that a pattern corresponds to what might be termed the facial syntax governing the arrangement of features—may be extracted, possibly through some mechanism like the “primal sketch” stage in Marr’s (1982) theory of perception.

Indeed, so biologically important is the identification of facial stimuli that some have argued that the facility is at least to some extent innate. In a rather obscure study by Goren, Sarty, and Wu (1975), for example, persuasive evidence was discovered for the attention-holding capacity of face-like stimuli shown to human neonates, which does not extend equally to faces with jumbled features. In fact, according to Meltzoff and Moore (1977) not just attention to faces but actual facial discrimination also may take place shortly after birth. Evidence for this claim centers on their observations that an infant will mimic certain facial expressions displayed by an adult. This capacity, they argue, normally may be important in the social bonding process between mother and baby. I do not wish to dwell on this line of evidence: it is contentious and not everyone has been able to replicate the observations of neonatal interest in faces (Hayes & Watson, 1981). The possibility remains, however, that facial configurations are such biologically significant stimuli for primates that a degree of hard wiring may be present that enables the early stage of face perception to occur without a learning stage being required (Ellis, 1981). One advantage of such a system may be that it is unlikely to malfunction. Indeed, it is most improbable that anyone viewing a face will erroneously encode it as some other object. The 1, 000 slips in person recognition collected by Young et al., for example, did not contain any such instances. Similarly, in the literature on cases of prosopagnosia it is striking that, in the vast majority of cases, faces are correctly categorized, though, of course, usually not specifically identified. For such patients facial features usually seem reasonably normal but they cannot be processed further to a state of complete recognition. In Bodamer’s (1947) third case, however, a degree of feature distortion was reported as was the case with the first patient described by Shuttle-worth, Syring, and Allen (1982). Further exceptions to the rule are to be found in cases where pronounced metamorphopsia occurs. Here faces may appear entirely distorted as in one of the cases reported by Whiteley and Warrington (1977), where the patient described faces as looking like fish heads. Psychotropic drugs also may produce distortions in face perception (Ellinwood, 1969). McKellar (1957) for exaniple, reported that mescaline may alter perception of the size of objects, including faces, and that distortions in shape also may occur.

Generally, however, distortions in facial features leading to an inability to assign correctly a face to the face category are rare, and even here they lead to perception of associated objects, like fish heads. More commonly, it would seem that the system actively selects ambiguous configurations such as those found in clouds and flames to interpret them as faces. By the same token, visual hallucinations and hypnagogic images, sometimes called “faces in the dark, ” frequently involve faces (McKellar, 1957). In other words, such a strong perceptual bias exists toward seeing patterns as faces that failures to assign a face correctly to the appropriate processing system are most unlikely.

Physical Analysis

When an object has been classified as a face rather than something else there then follows a process whereby it is categorized along a number of dimensions based upon physical features. It is not possible to establish at this juncture just how many dimensions there might be, but a cursory examination of the prosopagnosia literature suggests that the major ones may include sex, age, and complexion. Bornstein (1963) examined two prosopagnosic patients who were unable to distinguish male from female faces, and the patient described by Cole and Perez-Cruet (1964) had similar difficulties. Another of Bornstein’s cases involved a prosopagnosic patient who misclassified ages, being quite wrong when telling age from facial clues. Whiteley and Warrington’s (1977) second case of prosopagnosia thought all faces looked younger than they were. Their first case had difficulties in distinguishing white from black faces—an impairment also shown by patients described by Cole and Perez-Cruet (1964) and Shuttle-worth, Syring, and Allen (1982).

Although each of these examples may reflect difficulties in the operation of specific detection processes tuned to select various distinguishing features, it also is possible that they are the result of a fault in some mechanism common to the processing of all objects. This particular mechanism, for example, could involve the analysis of both the high and the low spatial-frequency information contained within complex patterns. Faces contain a range of spatial frequencies and, whereas it was once thought that the lower ones alone were entirely adequate for face recognition (e.g., Tieger & Ganz, 1979), it now seems clear that higher frequencies are equally useful for face discrimination (Fiorentini, Maffei, & Sandini, 1983). Under conditions of low contrast, facial discrimination may become particularly difficult because higher frequencies are not detected so easily and therefore only low frequency information may be effectively available. Indeed, Owsley, Sekuler, and Boldt (1981) demonstrated that a group of 74- year-olds were significantly less able than a group of 20-year-olds, with equivalent visual acuity, to detect and discriminate faces largely because of a diminished ability to detect lower spatial frequencies at low contrast levels (when high frequency information had all but disappeared for all subjects). Many proso-pagnosics complain that the world looks foggy or grey and that colors seem faded (Bornstein, 1963; Pallis, 1955), which may imply that ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Neuropsychology and Neurolinguistics

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- List of Contributors

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Foreword

- Chapter 1 Introduction: Processes Underlying Face Recognition

- Part I: Brain Damage and Face Perception

- Part II: Lateral Differences for Face Perception in Normal Subjects

- Part III: Neuropsychology of Facial Expression

- Author Index

- Subject Index