![]()

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend my heartfelt thanks to the many people who have generously shared their time and knowledge in the writing of this book.

First of all, thanks to those I interviewed, many of whom are quoted in the case studies. They provided information, contacts, references and insights, without which this book would not have been possible. My valued “brains trust” included David Perchard, Rose Read, John Gertsakis, Russ Martin, Brett Giddings, Garth Hickle, Michael Waas, Cynthia Dunn, Kathy Frevert, Carmel Dollisson, Janet Leslie, George Gray, Lindsey Roke, Karen Warmen, Elizabeth Kasell, Mike Sammons, Stan Moore, Steve Morriss, Paul-Antione Bontinck, Sophi MacMillan, Carl Smith, Chris Hartshorne and John Webber.

Special thanks to Russ Martin, Chief Executive of the Global Product Stewardship Council, who was enthusiastic about this project from the start and encouraged me along the way.

Thanks also to Patrick Crittenden, who has been a friend and colleague for many years, during which we have collaborated on consulting projects that explored the business case for energy efficiency and packaging sustainability. Some of the ideas in this book emerged from that collaboration and I owe a considerable debt to his insights.

Patrick Crittenden, Rose Read, Brett Giddings, Garth Hickle, David Perchard and Jade Barnaby also peer reviewed chapters and made innumerable suggestions for improvement. Naturally any errors or omissions that remain in the book are mine alone.

![]()

1

Introduction: evolution, key concepts and business drivers

Steward (noun): A person whose responsibility it is to take care of something (Oxford Dictionaries, http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/steward).

If you bought a soft drink or a pint of milk in the 1950s, it was sold in a heavy glass bottle. You returned the bottle to a shop, dairy or soft drink bottler and were refunded the deposit you paid with the original purchase. This was typical of the way that many other products were used, reused, repaired or repurposed, a practice Susan Strasser calls “the stewardship of objects”.1

These practices started to change after the Second World War, when the growing popularity of “disposable” or “throwaway” packaging led to the demise of the refillable glass bottle. An advertisement in 1947 for one of the earliest disposable bottles in the United States, manufactured by Owens-Illinois Glass Company, promoted its convenience for consumers, with the claim that, owing to this new, liberating system, there’s “No more bother lugging empties back for refunds!”2 In Australia, chemical manufacturer ICI claimed in 1967 that its polyvinyl chloride (PVC) bottles were “here to stay” because of their efficiency and convenience: “For the consumer, disposability is a strong point in favour of PVC bottles, as normal household incineration will adequately dispose of them . . .".3

Not everyone shared the industry’s enthusiasm for convenience, as new forms of glass, plastic and paperboard packaging contributed to a growing litter problem. In the US there were hundreds of proposals by local and state regulators to restrict the use of disposable containers. The first of these, in Vermont in 1957, “sent shockwaves through the burgeoning disposables industry”.4 Many of these proposals were defeated, at least in part because of intense lobbying by packaging and beverage companies. The industry, led by companies such as the American Can Company, Owens-Illinois Glass Company and Coca-Cola, created a not-for-profit organization—Keep America Beautiful (KAB)—which launched a national anti-litter education campaign. Many of the same companies later supported the development of recycling programmes to divert used containers, particularly glass and aluminium, from landfill.

While criticized at the time and more recently as “greenwashing”,5 anti-litter and recycling campaigns by the packaging and beverage industries were some of the earliest examples of what we would now call “extended producer responsibility” (EPR) or “product stewardship”.

1.1 The idea of producer responsibility: history and evolution

By the 1980s solid waste had become a high priority public issue in many developed countries because of declining landfill space, increasing costs of disposal and opposition to new landfills. Those who were actively involved in recycling and waste management at the time realized that the solution needed to go beyond the expansion of recycling systems run by local authorities. In the early 1990s Thomas Lindhqvist, an academic at Lund University in Sweden, proposed an innovative solution that he called extended producer responsibility. The aim of EPR was to reduce the total environmental impact of a product by making the manufacturer “responsible for the entire life-cycle of the product and especially for the take-back, recycling and final disposal of the product”.6

EPR is now widely accepted as the basis for product-related environmental policies in the European Union (EU). Beginning with packaging in the late 1980s, producer responsibility policies have now been extended to waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE), end of life vehicles (ELV) and batteries. Other countries including Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and many Canadian provinces have followed the European lead by introducing EPR laws for similar groups of products. By 2015 there were more than 90 laws in the United States (US) covering a wide range of products including appliances, batteries, carpets, mobile phones, electronics, mattresses, fluorescent lighting, mercury thermostats, used paint, pesticides and pharmaceuticals.7

A related but more inclusive term for producer responsibility is “product stewardship”. This is the principle that everyone involved in the manufacture, distribution or consumption of a product shares responsibility for the environmental and social impacts of that product over its life-cycle. Product stewardship tends to have broader scope than EPR: encompassing voluntary action by companies as well as regulated schemes; social as well as environmental impacts; and initiatives at every stage of the product life-cycle.

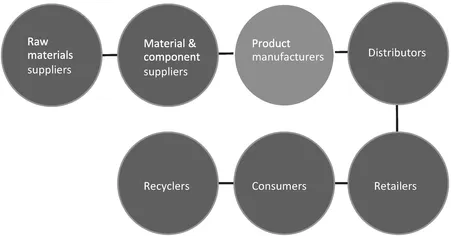

Producers—often defined to include manufacturers, brand owners and distributors—have a particularly important role to play because of their influence on suppliers, consumers and recyclability at end of life (Fig. 1.1).

Lindhqvist believed that producer responsibility could take many different forms, including economic or physical responsibility for collection, recycling or disposal of the company’s products. While acknowledging that the manufacturer, distributor, user, recycler and final disposer all influence the environmental impacts of a product and must be encouraged to do what they can, he argued for a focus on manufacturers because of their unique ability to prevent environmental impacts through environmentally conscious design.8

FIGURE 1.1 EPR focuses on the ability of manufacturers to influence the product life-cycle

While originally intended to cover the entire product life-cycle, the term “EPR” has generally been applied to regulatory initiatives that promote producer responsibility for waste management and recycling at end of life. The principle of EPR proposes a reallocation of responsibility for product waste management between industry, consumers and governments:

EPR extends the traditional environmental responsibilities that producers and importers have previously been assigned (i.e. worker safety, prevention and treatment of environmental releases from production, financial and legal responsibility for the sound management of production wastes) to include the management of products at their post-consumer stage.9

EPR programmes recognize that the environmental costs of waste management are not reflected in p...