- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Listening in Language Learning

About this book

Examines listening as both a means of achieving understanding and as a teachable skill. The underlying theme of the volume is that an integration of cognitive, social, and educational perspectives is necessary in order to characterise effectively what listening ability is and how it may develop. It introduces listening from a cognitive perspective, and presents a detailed investigation of listening in social and educational contexts. The study concludes with an analysis of how listening development can be incorporated effectively into curriculum design.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction: Listening in verbal communication

1.0 Comprehension or interpretation?

One of the most important concepts associated with verbal interaction is that of understanding. To what extent can we say that the interlocutors in any interaction understand each other? To what extent do they ‘comprehend’ through the words that an interlocutor uses and to what extent do they ‘interpret’ ideas that are related to the words that an interlocutor uses? Is understanding a mental phenomenon recoverable through probing the mind of the hearer or is it a social phenomenon recoverable through examination of subsequent behaviour by the listener? These are fundamental questions underlying linguistic inquiry in general, and are clearly of concern for applied linguists and language teachers. Without a realistic view of understanding in verbal interaction, it is difficult to uncover a sensible paradigm for conducting research and impossible to arrive at a coherent pedagogy for developing understanding.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide an introductory discussion of the role of listening in verbal communication. In doing this, I will review essential contributions to applied linguistics from other disciplines, contributions which have an impact on how we view listening. After the construction of a preliminary model of verbal understanding that will be developed in subsequent chapters, an outline will be given of some of the historical issues concerning listening in language teaching in order to set the stage for later chapters that deal with listening in a language curriculum.

1.1 Information-processing and inferencing-based approaches

To explore the issue of understanding in verbal interaction it is necessary to outline the nature of content in language and the nature of roles of the interlocutors. Practically speaking, before we look at how people understand language (or more precisely, how they understand events in which language is used), we need to know what it is that is understood, who is responsible for creating this understandable content, and who is responsible for understanding it.

Most of us will have some ready answers for these questions, or at least some useful metaphors to describe the process of understanding in verbal communication. Let us take a closer look at some of the definitions of language understanding that we commonly use. Many of the metaphors we casually use to think about verbal communication allocate distinct roles to a speaker and a listener. For instance, we often speak of communication as the sending and receiving of information, with our image of one person ‘catching’ this information that another person somehow ‘sends’. Or we often refer to communication as a travelling-thoughts process, with one party ‘picking up signals’ we transmit. Although these metaphors account for both content and roles of interlocutors, the actual procedures they imply are of course impossible to carry out. Thoughts and messages obviously do not possess the physical properties necessary to travel, nor do people literally follow, pick up, or catch things in the communication process.

Many of these transfer-of-information metaphors are rooted in the rationalist tradition in philosophy, the philosophy which gave rise to information processing theory. In the rationalist tradition, words were seen as having meaning:

To make Words serviceable to the end of Communication, it is necessary that they excite, in the Hearer, exactly the same Idea they stand for in the mind of the Speaker. Without this [People] fill one another's Heads with noise and sounds; but convey not thereby their Thoughts, and lay not before one another their Ideas, which is the end of Discourse and Language.

(John Locke, 1689)

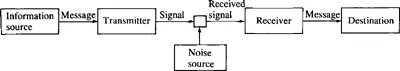

This rationalist view of communication was encapsulated in the popular information-processing metaphors of the 1940s (e.g. Shannon and Weaver, 1949), which viewed communication as a process which attempted to conserve the speaker's meaning — ‘the message’ — throughout a transmission process. The role of the receiver was to reconstruct the speaker's message as encoded in the signal (Figure 1.1).

FIGURE 1.1 An information processing model (from Shannon and Weaver, 1949)

Although this basic model was subsequendy modified to include listener feedback and noise distortion (e.g. Schramm, 1954; DeFleur, 1966; Dance, 1967), the fundamental information-processing paradigm remains: communication is seen as a potentially perfect encoding— decoding process, in which speaker and hearer approach an isomorphic match of meanings.

Within the transmission metaphor emerge some rather rigid views of what the receiver (the listener) does. Perhaps the most deeply ingrained set of metaphors are those which view listening as an outcome which can be measured quantitatively in relation to what language has been spoken. It is not uncommon to hear people say — particularly second language learners — that they have understood, say, 50 per cent of what a speaker said.1 The notion of quantity of understanding is apparently based on the belief that a speaker's message can be comprehended: a successful listener can actually enumerate structural units of some sort in what a speaker says and derive meaning directly from those units.

The information-processing model is useful as a hypothesis since it suggests answers to three questions:

(1) What is the content of verbal communication?

(Answer: information.)

(Answer: information.)

(2) Where does this content (i.e. the information) reside?

(Answer in the words the speaker uses.)

(Answer in the words the speaker uses.)

(3) How is understanding of the content achieved?

(Answer by the listener comprehending the words the speaker uses.)

(Answer by the listener comprehending the words the speaker uses.)

Although these are critically important questions in applied linguistics, the answers provided by the information-processing metaphor are at best overly simplistic and at worst possibly misleading. The information-processing model overstates the role of the denotative function of language, and distorts the role of the listener in the act of understanding. For these reasons the model must be re-examined.

The view of understanding that I wish to develop in this book is based on the growing theme in cognitive science that people construct rather than receive knowledge, and that understanding in verbal communication is a construction process. I will view verbal communication in terms of relevance theory (Sperber and Wilson, 1982, 1986) which holds that communication is fundamentally a collaborative process involving ostension (production of signals by a speaker) and inference (contextualizing those signals by a hearer).

Ostension, as an act by one interlocutor which is physically perceivable by another, provides two layers of information. First, there is the information which has been pointed out; second, there is the information that the first layer of information has been pointed out. For example, if you and I are sitting together in a room and I know that you like snow and I know that it is just beginning to snow outside and I open the curtains so that you can see the snow falling for yourself, I have performed an ostensive act of communication by opening the curtain.

In terms of relevance theory, for you to understand this act of ostension, you have to understand not only the first layer of information (that it is snowing now) but the second layer of information as well (that I wanted you to see it now). The first layer might be termed the ‘locution’ and the second layer might be roughly termed the ‘illocution’. I, the actor, had some intent in providing this locution to you.

Understanding the ostensive act is an inferential process of finding a relevant link between the two layers of information. It is vital to note here that the relevant link that you find to make sense of the communicative act need not be the only relevant link you could find, nor need it be the link that I had hoped you would find. You can achieve an acceptable understanding without knowing exactly what I had intended.

This placement of responsibility for interpretation on the hearer is a direct departure from the information-processing view of understanding. Relevance theory places responsibility for constructing an acceptable understanding (finding a relevant link) on the listener. This view suggests that understanding involves both decoding processes (in the example so far, you would need to be able to recognize the snow) and inferential processes based on the speaker's actions, which may be both verbal and non-verbal.

When speech is involved in ostensive acts, as it is in verbal communication, the interlocutors use inferential processes in the same way. If, for example, instead of opening the curtains for you to see the snow, I come in from another room and say, ‘Hey, it's snowing’, the inferencing you must do to understand my ostensive act (here, my saying, ‘Hey, it's snowing’) is the same, although the decoding process is different. You still must find a relevant link between the first layer of information (my claim that it's snowing) and the second layer of information — that I pointed this out to you now.

An important aspect of relevance theory, and a fundamental departure from the information-processing view of communication, is that successful ostensive-inferential communication cannot be guaranteed. There is no procedu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Series list

- General Editor's Preface

- Chapter 1 Introduction: Listening in verbal communication

- Chapter 2 Auditory perception and linguistic processing

- Chapter 3 Listener inference

- Chapter 4 Listener performance

- Chapter 5 Listening in transactional discourse

- Chapter 6 Development of listening ability

- Chapter 7 Assessing listening ability

- Chapter 8 Listening in a language curriculum

- References

- Glossary and transcription conventions

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Listening in Language Learning by Michael Rost,C N Candlin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.