![]()

Part 1

The Crowded Planet

Books on sustainable business usually start in the same way. “All is not well on Planet Earth”, they explain; we are in a deep and dangerous ecological mess. These opening chapters invariably feature football pitches or Olympic-sized swimming pools to help readers grapple with the scale of the environmental challenges, supported by pronouncements from prominent business leaders, politicians and celebrities.

Part 1 is my version of “All is not well on Planet Earth”. But, rather than repeating crisis talk readily available elsewhere, this part instead addresses what I see as the main shortcoming of this chapter archetype: the failure to get to why pollution and wastes are created in the first place, and why they become such a problem. We explore this question in Chapter 1: What is it about the conditions we live in, what is it about the Planet, which means our activities have created such an ecological mess? Once we have identified the characteristics of our Planet and human activities on it, we can go about answering a further important question, far more accurately now that we have got to the root causes of unsustainability: what needs to happen to get out of this ecological mess? This is the question we explore in Chapter 2.

Part 1, then, is about the (very) big-picture context—the planetary scale— in which the global economy, and business activities of every single business that exists takes place. If we want to understand how individual companies are affected by, and affect, this bigger-picture context, we first need an accurate understanding of the conditions for sustainability, the current context of unsustainability, and what is required to get from the second to the first. So let’s take a step back and have a closer look at Earth and its 7 billion Earthlings—a Crowded Planet.

![]()

1

The economy-in-Planet

A first, unsurprising fact: All economic activity takes place on Planet Earth. And yet most of us are pretty ignorant about our planetary host. This chapter goes back to basics. It is first about the Planet, and how it creates opportunities for, and constraints on, economic activity. It also defines the characteristics of a new, sustainable economy, congruent with its planetary host: the “economy-in-Planet”.

The economic system is supported and constrained by its host planetary system

First and foremost, Planet Earth is a system. What is a system? Systems-thinking pioneer Donella H. Meadows defined a system as an “interconnected set of elements that is coherently organised in a way that achieves something” (Meadows, 2008). Like other systems, Planet Earth clearly has different elements: a biosphere, a lithosphere (or crust), an atmosphere, a hydrosphere. These elements are interconnected, for example through water cycles, the greenhouse effects and volcanic activity. Like other systems, the Planet can be understood as having stocks, flows and feedback loops. Its stocks are what we sometimes call resources: ores, metals, biomass (we return to these later); solar energy flows into the system from outside; and feedback loops that sometimes allow the system to achieve a certain stability (as with climate regulation) and sometimes create the potential for fundamental transformation (such as possible runaway climate change).1 Over the past 10,000 years, these elements—stocks, flows and feedback loops—have together created stable, self-regulating, conditions perfect for the flourishing of human life.2

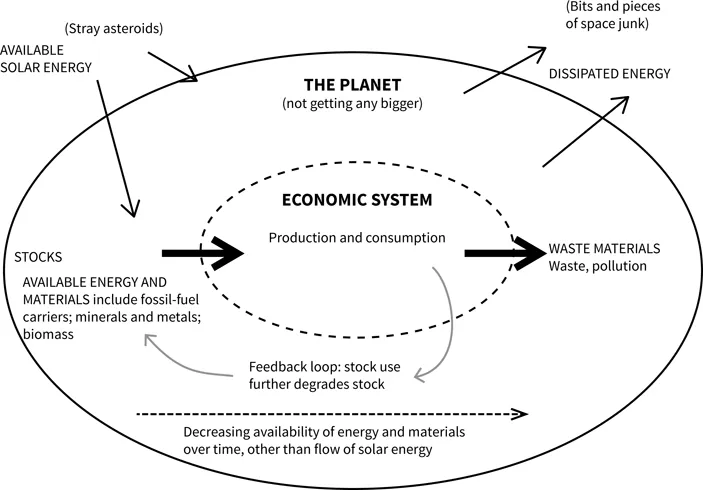

In addition, the Planet is a closed system; in other words, it exchanges energy with its surroundings, but not matter. The Planet receives solar energy, and releases heat into the surrounding atmosphere; but that’s it. No significant materials are exchanged with space (other than a few rockets and stray asteroids). As a closed system, Earth is subject to the Second Law of Thermodynamics, also known as the entropy law, which states that available energy that we can use is continuously transformed into dissipated energy that we cannot use (Atkins, 2010). In better news, the inflow of solar energy the Planet receives from space can be used as energy before it dissipates back into space.

One final but crucial point about the planetary system: it’s not getting any bigger. We cannot hope for an increase in the quantity of available materials and resources; the Planet, at its permanent, stable size, is all we’ve got.

These planetary characteristics are not quirky facts, but rather are crucial for understanding our economy. The Planet is after all where we conduct our business activity—as well as being where you and I, and everyone else, lives. The economy, then, is a sub-system of the planetary system: it takes place within it. And it relies entirely on its host system, the Planet, for its material basis, in a deep, irrevocable interrelationship.

Unlike the Planet, the economic system is open—that is to say, it exchanges both energy and matter with its host. Materials and energy flow from the natural world enter the socio-economic sub-system, are used, and are then ejected as waste and dissipated energy back into the planetary system. All our resources come from the Planet, and all our wastes go back into it as well. Moreover, the economic system is subject to the same laws and behaviour patterns of its host system. For example, the economic exploitation of planetary resources is fundamentally entropic: transforming valuable, low-entropy materials and energy into unusable, high-entropy materials and energy. This process is linear, and largely irreversible (although it can be delayed through recycling)—this is why we can’t reuse oil again and again (Georgescu-Roegen,1975).3 And, lastly, there are final limits to the material growth of the economic system, since the Planet itself isn’t growing: our supplies of freshwater, minerals, timber and fossil fuels are ultimately finite. As Donella H. Meadows observed, “No physical system can grow forever in a finite environment” (Meadows, 2008: 59).

If we conceptualise our society and economy accurately within its environment, our Planet, it might look something a bit like Figure 1.1.

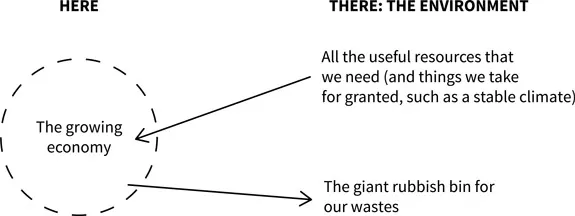

Yes, this is all a bit complex and confusing, but it nonetheless gets at something important. Part of the difficulty with this representation is that it differs so much from how we usually understand our relationship with the environment, which instead looks a bit like Figure 1.2.

This schema imagines our economy as separate from the environment. Sure, somewhere out there, there is something called the environment, which conveniently provides us with resources and an outlet for our pollution. But Nature is there for the picking, and the economy can grow in line with our desires. This view has prevailed since the Industrial Revolution, and it gives us an instrumental, anthropocentric view of the natural world, where nature is of interest principally as a resource. It is the view that has created the economy of the industrial era, the unsustainable economy that we have inherited, and continue to live with, today—what I call the legacy economy. There are obvious limitations to this view, but, for now, let’s keep our anthropocentric hat on and try to answer the following question: what has the Planet ever done for us?

Figure 1.1 The economic and planetary systems

Figure 1.2 Common misconception of the relationship between the economy and the environment

This diagram is inspired by Figure 1 in Rees, 2011.

The Planet creates the opportunity for economic activity through resources, sinks and natural regulation

Our Planet supports our economy in three ways: by providing us with the resources that we need, by providing sinks for the waste we produce, and by providing viable conditions in which to conduct our activities, through its regulatory capacity.

The most obvious way in which the Planet supports our activities is through resources—these are the planetary stocks I mentioned earlier. Resources provide the material basis for all business activity. Even services are more reliant on “stuff”—on natural resources—than their name suggests. A trip to the hairdresser will require cotton to clothe the hairdresser, fossil fuels to make and power the hairdryer, and wood for the customer’s chair. There are four broad categories of resources: biomass, construction minerals, fossil energy carriers, and ores and industrial minerals.4 As all economic activities require some resource use, in general a growing economy requires growing resource use. And all evidence suggests this is true. Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, global consumption of these resources has grown at an unprecedented rate, with a further dramatic increase since the end of the Second World War and an 80% growth in the last 30 years alone (Dittrich et al., 2012). Globally, we now use between 60 and 70 billon tons (Gt) of materials per year, or in the region of 9.2 tons per capita, representing an eightfold increase in the last 100 years.5 We are munching our way through planetary resources at an extraordinary speed. This raises a critical question: will resources be able to support forecast growth, or will the economy ultimately be constrained by the finite nature of the Planet and its stocks?6

The answer varies from resource to resource. Given the central importance of fossil fuels in our economy, much effort has been expended to figure out if—or when—we will run out of oil. Attempts to estimate oil reserves go back to the 1950s, when M.K. Hubbert predicted that oil production in the United States would “peak” between 1965 and 1971.7 But attempts to predict the timing of peak oil production have not been easy thanks to the ongoing discovery of new fields and the exploitation of “unconventional” sources. Some now give a date of 2020; but, in the meantime, we are actually in the midst of an oil and gas boom. In other words, we are not “running out of oil” in the immediate future; rather, according to BP, we have at least half a century of proven reserves ahead of us, to meet the needs of global consumption.8 As for other fossil fuels, we have at least 64 years of natural gas and 112 years of coal. Since these figures refer only to proven reserves, they are likely to be massive underestimates. The situation for metals and minerals varies significantly depending on the particular material. Some, such as aluminium, iron and magnesium, are plentiful in the Planet’s continental crust. Construction materials such as sands, gravel and limestone are also plentiful. For other metals and minerals, estimating remaining reserves can be difficult. These are sometimes revised downward as ore is mined and extraction becomes more difficult. More frequently, they are revised upward as new deposits are discovered, or as the potential to exploit existing deposits is increased. Estimated copper reserves in 2012, for example, were more than double the 1970 estimate (US Geological Survey, 2013). “Rare metals” are, obviously, scarcer, but, as for fossil fuels, any economic constraint due to scarcity of metals and minerals does not seem imminent.

The situation for biomass is considerably more alarming, and we are already in what one study describes as a situation of “ecological overshoot”: that is to say, globally, our use of biomass is so great that it is undermining its replenishment. On a regional level, there is also considerable mismatch between biomass endowment and consumption. Most European countries “ran out” of biomass centuries ago, supplementing home production through trade or conquest. The latest version of this transfer of biomass from poor to rich are modern-day “land grabs”: foreign companies and countries purchasing large tracts of productive African lands to supply their customers or citizens, often with devastating effects for local populations (ETC Group, 2011).

The second way the Planet supports economic activity is by providing sinks. The Planet acts as a sink when it absorbs our spent energy and used materials that have left the economic sphere and re-entered the planetary system as waste and pollution. Remember, as the Planet is a closed system, there is no outside—nowhere to put waste and pollution away: it stays within the system. While we have to date not spent much time thinking about the Planet’s sink capacity, it is becoming clear that pollution and waste are now reaching extraordinary volumes, with devastating consequences for some ecosystems (think of the plastic islands floating around the Pacific Ocean, or the contamination of rivers and landscapes around mining operations). This is in turn affecting resource availability and quality of future resources, as well as interfering with the Planet’s third function.

Perhaps the most serious impact of resource extraction, pollution and waste is on the Planet’s regulatory capacity: that is to say, on the stable condition, the natural cycles that enable life on Earth. Much like the Planet’s role as a sink, we have pretty much taken this capacity for granted, and are only starting to notice it as it appears not to be working quite so well. For example, we now know that the use of neonicotinoid pesticides has had devastating impacts on bee colonies, affecting the yearly cycle of crop pollination. The global cycles of nitrogen and phosphorus may not be as visible as the honeybee, but they have been seriously disturbed by intensive agriculture, and this will affect future biomass resources. Climate change, belatedly recognised as the greatest challenge of our time by all major world leaders—described by Barack Obama as the “one issue that will define the contours of this century more dramatically than any other”, and by Ban Ki-moon as the “defining issue of our age”—is itself a problem of the Planet’s regulatory capacity.9 The failure of climate regulation is caused by the inability of a sink (the atmosphere) to absorb the pollution output (CO2 and other greenhouse gas [GHG] emissions) generated through intensive use of a resource or stock (fossil fuels [with land use changes also contributing to increases in CO2 concentrations]). Global GHG emissions due to human activity have grown significantly since the Industrial Revolution, with an increase of at least 70% in the last 40 years (IPCC, 2007).10 The last time the atmosphere had so much CO2...