This is a test

- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Britain and Latin America in the 19th and 20th Centuries

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The first full-length survey of Britain's role in Latin America as a whole from the early 1800s to the 1950s, when influence in the region passed to the United States. Rory Miller examines the reasons for the rise and decline of British influence, and reappraises its impact on the Latin American states. Did it, as often claimed, circumscribe their political autonomy and inhibit their economic development? This sustained case study of imperialism and dependency will have an interest beyond Latin American specialists alone.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Britain and Latin America in the 19th and 20th Centuries by Rory Miller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

THE GROWTH AND DECLINE OF BRITISH INTERESTS

‘Spanish America is free,’ George Canning, the British Foreign Secretary, asserted in December 1824, ‘and if we do not mismanage our affairs sadly, she is English.’1 Almost at the very moment that Canning wrote, the Latin American wars of independence were drawing to a close with the defeat of the Spanish forces in Peru at the decisive battle of Ayacucho. Britain’s future in the region seemed assured. The leaders of the new nations regarded diplomatic recognition by the United Kingdom as essential for both their economic development and their political security. Canning’s sense of triumph was motivated by the fact that he had finally persuaded his colleagues to consent to negotiations with Mexico, Gran Colombia and Buenos Aires for commercial treaties which might provide a more solid basis for Britain’s trade with the new nations.

Canning’s success in advancing Britain’s economic interests during the period of Latin American independence marked the culmination of more than two hundred years of attempts by privateers, merchants and ministers to break into the monopoly of the Spanish and Portuguese empires and to promote Britain’s influence there against its commercial rivals, particularly the French. Statesmen and businessmen had long believed that the maladministration and inefficiency of the Iberian colonies in the New World concealed tremendous potential wealth, especially in the form of unexploited gold and silver deposits. For mercantilist theorists, who visualised a nation’s power in terms of its ability to accumulate bullion, the prospect of breaking into the Iberian monopoly was irresistible. While mercantilism lost its dominance as a mode of economic thought at the end of the eighteenth century, the avaricious capitalists of the early Industrial Revolution were equally tempted by opportunities to sell cheap cottons to people in Latin America who had been starved of access to foreign trade or to gain control of the renowned silver mines of Peru and Mexico.

The first real concessions came in 1810, when the British government negotiated preferential trading privileges in Brazil in return for its support for the Portuguese royal family during the Napoleonic Wars. In the Spanish empire, where the struggle for emancipation lasted from about 1810 until 1825, restrictions on direct trade between the colonies and other countries were gradually dismantled during the conflict. When it finally became clear, in the early 1820s, that Spain could do little to reverse the independence process, Canning took the first steps towards safeguarding Britain’s economic interests and recognising the new republics by sending out consular officials. The British mania for Latin America rose in a crescendo early in 1825, just after the government’s decision to grant formal recognition to some of the new nations. Merchants with cargoes of manufactured goods, particularly cotton textiles, established themselves in large numbers in ports along the Atlantic and Pacific coasts, while in London eager speculators invested their savings in loans to the young governments and in mining enterprises which promised a new El Dorado.

In practice, the reality proved somewhat disappointing. The speculation in loans and mining stocks turned suddenly into a commercial and financial crisis. Almost all the new governments, unable to raise the revenue they required to pay interest on their bonds, defaulted on the loans they had contracted in London. The mining companies largely failed, and the saturation of markets in Latin America brought ruin to merchants. Many republics lapsed into dictatorship or political anarchy, further hindering the development of economic relations with the outside world and prompting calls in Britain for government intervention to provide some security for business interests. For twenty years commercial relations with Latin America appeared to stagnate. Contemporary estimates of exports to the region in 1845 valued them at only £6.0 million, compared with £6.4 million twenty years before. At least a third of this trade was with one country, Brazil.2

The timing of the recovery varied from one country to another. Brazil never defaulted on its debt, and its trade always remained relatively healthy even when that of other countries collapsed. Elsewhere signs of revival began to appear in the 1840s, just at the time when the British government, through the abolition of import duties, colonial preferences and shipping restrictions, was instituting the system of ‘free trade’ which would endure until the 1930s. Latin America’s exports began to grow in value. Products like hides and wool from the River Plate, copper from Chile and guano from Peru found markets in Britain and elsewhere in Europe. The expansion of trade, and hence revenues, permitted governments to start to renegotiate the loans of the independence era.

During the subsequent decades the economic links between Latin America and Britain intensified. British and continental European markets grew rapidly and the costs of shipping began to fall, facilitating the export of bulkier products like wheat. Increasing numbers of British firms offered commercial services to Latin American producers and consumers, expanding the supply of credit, insurance, transport and marketing facilities. Britain’s own exports to Latin America rose in value to £13.6 million in 1860.3 National and provincial governments began to issue new bonds on the London capital market, while, for the first time since the collapse of the mining enterprises in the 1820s, numerous companies were floated on the Stock Exchange to invest in activities like railways, public utilities and commercial banking.

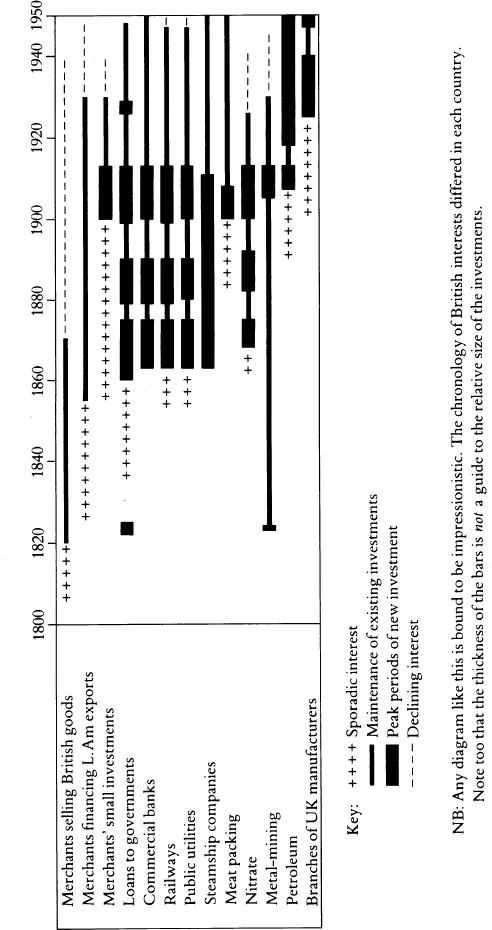

Figure 1.1, which outlines the timing of British economic activities in Latin America, illustrates the significance of the 1860s and 1870s for the growth and diversification of British interests. At the same time a marked change in their geographical focus occurred. While Brazil remained attractive, the old colonial mining centres, Mexico and Peru, lost much of their importance. The Anglo-French intervention of 1861–62, which resulted in the imposition of the Austrian Archduke Maximilian as emperor of Mexico, led to a rupture in diplomatic relations with Britain which lasted for almost twenty years. In Peru the ‘guano age’ drew to a close in the 1870s with default on the massive foreign debt which the country had incurred, followed swiftly by defeat in war with Chile and the loss of its valuable guano and nitrate reserves. British interest thus came to focus more on Brazil and the three southern republics, Argentina, Uruguay and Chile.

Between 1870 and 1914, despite setbacks caused by commercial and financial crises in the mid 1870s and the early 1890s, Britain’s economic interests in Latin America reached their peak. In the major countries their influence appeared pervasive and almost unassailable. Already, in the 1890s, even before the astounding growth of Britain’s interests in the River Plate which occurred between 1900 and 1914, the United States consul in Buenos Aires had claimed: ‘It almost seems that the English have the preference in everything pertaining to the business and business interests of the country. … They are “in” everything, except politics, as intimately as though it were a British colony.’4 Apart from their role as Argentina’s leading trading partner British businessmen accumulated substantial investments in government loans, railways, public utilities, commercial banks, meatpacking plants, and land in Argentina. These assets represented almost 10 per cent of Britain’s total overseas investment in 1913.5 In Brazil, where the level of Britain’s trade grew more slowly, they still appeared to possess a dominant role in public finance, shipping, the import trade, export credit, railways, cables and telegraphs. They had even obtained concessions to install a radio network. British investments in Mexico also expanded noticeably early in the twentieth century, despite the twenty-year hiatus in relations after 1867 and the United States’ domination of Mexico’s trade. In addition Britain possessed important interests in Peru, Chile and Uruguay, and many smaller investments elsewhere. Commentators in both Latin America and the United States began to believe in the existence of a close alliance of merchant bankers, companies and government officials defending and promoting British interests.

Figure 1.1 Chronology of British economic interests in Latin America

Yet by the middle of the twentieth century Britain’s influence had disintegrated. The First World War permitted the United States to gain ground in Latin America at the expense of the European powers. It also transformed Britain from a substantial international creditor into a debtor, making it impossible for the City of London to regain its prewar eminence in the supply of overseas finance. In the 1920s the majority of new foreign investment in Latin America came through New York. The Depression, and the advent of Imperial Preference in Britain in the early 1930s, added further blows. Trade declined, and Britain’s investments in the region, with the exception of the petroleum and manufacturing interests which had been growing since the turn of the century, became largely unprofitable. Moreover, the oil companies, railways and public utilities all came under increasing attack from nationalist critics.

The Second World War reduced trade further and put Britain into debt to the major Latin American countries as well as to the United States. By 1945 Britain’s exports to the region amounted to less than a quarter of their 1938 level.6 Over the next few years many of the pre-1914 investments, which had become almost worthless, were surrendered to Latin American governments in exchange for a cancellation of Britain’s debts. While a handful of the old railway and utility companies and merchant houses remained in business after 1950, the only truly significant investments left were Royal Dutch-Shell’s interests in Venezuela, the Bank of London and South America’s branch network, and a few manufacturing companies. Both for the British government and for many businessmen, Latin America, in contrast to the United States, Europe and the Commonwealth, no longer possessed any real significance.

THE EVOLUTION OF LATIN AMERICA7

At the time of independence Latin America was still, in many respects, a frontier of European colonisation. Apart from the principal centres of pre-Columbian civilisation in highland Mexico and the Andes, Spanish and Portuguese settlements were largely concentrated near the coast. Much of the interior – the Amazon and Orinoco basins, the lowlands to the east of the Andes, Patagonia, the deserts of northern Mexico (which then included California, New Mexico, Arizona and Texas) – remained beyond their control. Population was sparse and the principal cities and ports small. The Peruvian census of 1827, for example, suggests a population of about 1.5 million, almost two-thirds of whom were ‘Indian’. Lima, the capital, had only 60,000 people.8 Brazil in 1819 had a population of about 3.6 million, almost one-third of them slaves.9

Enormous disparities in wealth, income and social status were evident everywhere in Latin America. Small ‘white’ elites comprising merchants, bureaucrats and landowners dominated countries in which most people were of mestizo (mixed race), African or indigenous descent. In Brazil, the surviving Spanish colonies in the Caribbean (Cuba, Puerto Rico and eastern Hispaniola), and parts of the Peruvian, Colombian and Venezuelan coasts, slavery remained essential to commercial agriculture. Elsewhere both mineral production and primitive manufacturing, as well as the large haciendas which often dominated the countryside, depended heavily on the labour of the indigenous population. Yet despite the poverty of many of the region’s inhabitants, complex networks of internal trade and migration had developed, especially, but not only, close to the mining centres. Agricultural commodities such as grain, sugar and wine, imported manufactures, artisan products like textiles, and other goods like mules, cattle, salt and, in the Andes, coca were widely traded.

Independence obviously stimulated a wholesale reorientation of Latin America’s external economic connexions. The struggles also caused serious disruption to the domestic economies of the new states. The Spaniards fleeing to the remaining colonies in the Caribbean or to Europe and the Portuguese who left Brazil took with them considerable amounts of capital. The warring armies seized cattle, food and mules, and recruited new soldiers in every area through which they passed. The loss of transport animals and money both disrupted existing commercial networks. Arable production normally recovered fairly quickly from the damage caused by war, but mining was more seriously harmed, for the stoppages often caused flooding and hence the need for new capital expenditure to restore output. Moreover, the newly independent governments were faced with a mass of claims upon them, especially from those who had supplied goods to the military or seen their property confiscated.

Despite their success in achieving independence the ‘patriots’ left the political future of Spanish America undefined. Liberal hopes of political stability and constitutional progress were almost everywhere quickly disappointed. Instead, the new republics, with the exception of Chile, lapsed into what liberals, and many foreign commentators, viewed as the anarchy of the caudillos. While some constitutional norms such as periodic elections and sessions of Congress might still be observed, most governments seemed to rise and fall on the whim of the military veterans of the independence wars.

The precise reasons for the political instability and its nature varied from one country to another, but there were some common problems. One was that most governments remained desperately short of money. In the Andes the liberal ideal of eliminating legal distinctions based on ethnicity was quickly reversed; by the end of the 1820s colonial taxes on the indigenous populations had been reimposed under new names simply to raise revenue. These ‘contributions’, besides confronting liberal sensibilities, were difficult to increase. Apart from minor property and production taxes, therefore, the most obvious source of income for the new states was foreign trade. However, success in collecting import duties in adequate amounts was often limited, for it depended on the probity of officials, their ability to reduce contraband, and the level of economic activity. In addition, many governments incurred much greater expenditure than they had anticipated; the new loans which they obtained to cover the deficits, usually from local merchants, simply added to the claims arising from the independence struggles, thus increasing the internal debt.

Closely associated with these fiscal problems were the problems of external security and the intense civil conflicts which developed after independence. Mexico faced an invasion from Spanish forces in 1829, the secession of Texas in 1835–36, a French intervention in 1838, and war with the United States in 1846–47. Buenos Aires and Brazil fought over ownership of the Banda Oriental (modern Uruguay) from 1825 until 1828. Attempts at federation in Gran Colombia, Central America and Peru–Bolivia all disintegrated in the decade after 1829. Struggles within the republics also increased in bitterness, due to ideological disputes over the role of the church, constitutional questions like the relationships between the executive and legislature or national and provincial governments, and the economic conflicts which developed among different provinces or sectors of the elite. Military caudillos, who often possessed considerable popular appeal, allied themselves with particular groups within the civilian elites. As instability increased, power often trickled away from the national capitals towards the regions.

The outcomes of the political struggles varied. Mexico, Peru and Bolivia all provided extreme examples of instability. Between May 1833 and August 1855 the Mexican presidency changed hands thirty-six times; at the peak of the conflict, between 1835 and 1840, twenty ministers of finance held office.10 In such countries the central government’s inability to obtain revenues, and the bitterness of ideological and economic conflicts within the elite, made it impossible for any one leader to create a coalition powerful enough to preserve order for any length of time. Elsewhere, however, certain caudillos did succeed in establishing more stable governments by constructing firmer alliances with landowners and regional leaders, developing their popular support and, at times, eliminating their opponents by force. In Paraguay José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia remained in power from 1814 until his death in 1840, creating a mestizo nation largely isolated from the outside world and under his personal authority. In the River Plate, Juan Manuel de Rosas, a leading estanciero (cattle-rancher) who became governor of Buenos Aires in 1829, dominated Argentina by means of alliances with other provincial governors, the support he cultivated among poorer urban groups, and the occasional use of terror, until rival caudillos from the littoral...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures and Maps

- Abbreviations

- Glossary

- Preface

- 1. Introduction

- 2. The Origins of British Interest in Latin America: the Colonial and Independence Eras

- 3. The British Government and Latin America from Independence to 1914

- 4. Latin America and British Business in the First Half-Century after Independence

- 5. The Merchants and Trade, 1870–1914

- 6. The Investment Boom and its Consequences, 1870–1914

- 7. Three Perspectives on the Links with Britain before 1914: Argentina, Brazil and Chile

- 8. The First World War and its Aftermath

- 9. The Loss of British Influence: the Great Depression and the Second World War

- 10. The Relationship between Britain and Latin America in Retrospect

- Appendix: Chronological Table

- Bibliographical Essay

- Select Bibliography

- Maps

- Index