In the aftermath of World War II, there was increasing concern among the international community about the long-term protection of cultural and natural heritage sites and out of this growing recognition emerged the concept of a common heritage for humanity. The Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage, known henceforth as the World Heritage Convention, was adopted by the General Conference of UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) in 1972. As noted in the preamble to the convention, there was a general awareness that ‘the cultural and natural heritage are increasingly threatened with destruction not only by the traditional causes of decay, but also by changing social and economic conditions which aggravate the situation with even more formidable phenomena of damage or destruction’ (UNESCO, 1972).

Since the World Heritage Convention came into force, the rate of change of social, economic and environmental conditions globally has continued unabated. The concept of sustainable development has emerged in response to the resulting environmental concerns and it is promoted across the globe as a means to address the vastly complex environmental and societal problems in an equitable and integrated fashion for both current and future generations. As the World Heritage Convention aims to protect the world’s diminishing cultural and natural resources, it is important to ask by what means the concept of sustainable development has been incorporated into the ethos of the convention and how the principles of sustainability are practised through the global network of World Heritage properties. The convention needs a coherent strategy to determine the desired goals of the sustainable development of World Heritage properties.

This chapter provides a contextual background to the World Heritage Convention and outlines the historical background and the shift towards the concept of a heritage of humanity. The role of World Heritage in the context of sustainable development is considered as well as the question of what sustainable development means in practice. Debate and definitions of sustainable development have initially rested on three dimensions: the economic, the environmental and the social. Until relatively recently ‘culture’ has often been overlooked as a significant component and this chapter considers its promotion as a fourth dimension. UNESCO, the United Nations (UN) System and the role of other conventions that are linked to the World Heritage Convention in conservation and sustainable development are also explored.

Evolution of the World Heritage Convention

The history of the World Heritage Convention is tied to the emergence of UNESCO following the establishment of the UN in 1945. The inter-governmental body of UNESCO was formed in the hope of perpetuating peace, through ‘humanity’s moral and intellectual solidarity’ (UNESCO, 1945, preamble). UNESCO gained recognition as a neutral international organization that could assist in the reconstruction of education systems and culture in war-torn countries. This put it in a unique position to generate international support to rescue the Nubian monuments in Egypt in light of development plans to build the Aswan High Dam on the river Nile.

The convention emerged as a tool to unify the member states of the UN in safeguarding heritage, a unique and irreplaceable property ‘to whatever people it may belong’ (UNESCO, 1972, preamble). The emphasis is on the concept of heritage for all humankind and of the international community’s responsibility to protect and conserve it through interdisciplinary means.

Formation of UNESCO

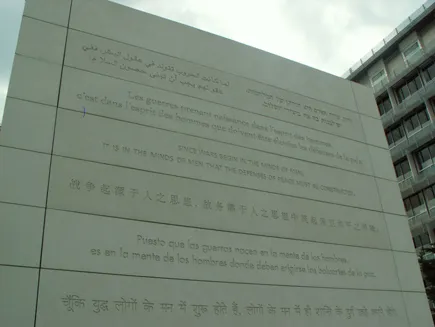

The United Nations was formed by 51 countries in 1945 to replace the League of Nations which had failed in its mission after World War I to ‘promote international cooperation and to achieve international peace and security’ (League of Nations, 1919, preamble). Soon after its formation in October 1945, the UN held a conference for the establishment of an educational and cultural organization. This organization was to secure a lasting peace based on advancing mutual understanding between peoples through education and the spread of culture and, consequently, the UN Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization was founded (UNESCO, 2012a). The preamble of the UNESCO Constitution captures this sentiment of peace and understanding by stating: ‘since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed’ (UNESCO, 1945, preamble). This message is engraved in ten languages on a stone wall standing in the Square of Tolerance at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris, inaugurated in 1996 (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Stone wall at Tolerance Square, UNESCO headquarters in Paris (credit: Elene Negussie)

The promptness with which UNESCO was founded following the establishment of the UN was due to the prior efforts of the Conference of Allied Ministers of Education (CAME) held during World War II. CAME promoted the establishment of an international educational organization out of concern for the need to reconstruct education systems after the war. The early conception of an intellectual and educational organization necessary for the construction of a peaceful, democratic and civilized international society proved popular and the endeavour gathered momentum following ratification of the UN Charter (Mundy, 1999).

UNESCO’s formation should therefore be understood in the context of post-war feelings and the shared conceptualizations of an ideal post-war world order. This collective vision had been set in motion by the Atlantic Charter of 1941. The Charter was a policy statement drafted by President of the USA, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and British Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, and agreed by the Allies, which set out ‘certain common principles on which they base their hopes for a better future for the world’ (Atlantic Charter, 1941, para2). The eight goals included self-determination of peoples, freer trade and ‘assurance that all the men in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want’ (Atlantic Charter, 1941, para8). The Charter inspired the creation of multilateral institutions such as those agreed at the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944 (the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT); the International Monetary Fund (IMF); and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD, today the World Bank), as well as the Declaration of Human Rights, the first draft of which was considered at the first session of the UN General Assembly in 1946). Unlike earlier forms of multilateralism, the post-war agreements and charters promoted concern for issues of social policy and human well-being as well as setting goals for security, peace and establishment of a stable, liberal, world economy. Furthermore the Atlantic Charter had set an unconventional precedent as an international instrument that recognized individuals or ‘all men in all lands’ rather than limiting its scope to the interests of the traditional sovereign nation states (Borgwardt, 2006).

These sentiments are reflected in the UNESCO Constitution which declares that ‘a peace based exclusively upon the political and economic arrangements of governments would not be a peace which could secure the unanimous, lasting and sincere support of the peoples of the world, and that the peace must therefore be founded, if it is not to fail, upon the intellectual and moral solidarity of mankind’. Furthermore, ‘the wide diffusion of culture, and the education of humanity for justice and liberty and peace are indispensable to the dignity of man and constitute a sacred duty which all the nations must fulfil in a spirit of mutual assistance and concern’ (UNESCO, 1945, preamble). Consequently, UNESCO’s mission statement as defined in its Constitution is ‘to contribute to peace and security by promoting collaboration among nations through education, science and culture in order to further universal respect for justice, for the rule of law and for the human rights and fundamental freedoms which are affirmed for the peoples of the world, without distinction of race, sex, language or religion, by the Charter of the United Nations’ (UNESCO, 1945, article 1). UNESCO’s mandate continues to be highly relevant as culture is increasingly at the frontline of conflict with extremist groups such as the so-called Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) in Iraq and Syria targeting individuals and groups on the basis of their cultural, ethnic or religious affiliation. The ongoing systematic nature and scale of attacks on culture highlight the strong connection between the cultural, humanitarian and security dimensions of conflicts.

International safeguarding campaigns

The identity of UNESCO as a neutral, multilateral agency dedicated to furthering peace and security was critical to the success of its landmark project to save the Nubian monuments of Egypt and Sudan. In 1954, the Egyptian government put together a proposal to build the Aswan High Dam on the River Nile. This was at a time of political instability in the region, following a military coup in Egypt in 1952 and the forced withdrawal of British troops from the Suez Canal in 1954. Funding from the World Bank for the construction of the dam fell through and Egyptian President Abdel Nasser accepted aid from the former Soviet Union. The situation was further complicated when President Nasser nationalized the Suez Canal, which provoked a widely condemned invasion by Israeli and Anglo-French forces. During this time UNESCO supported the establishment of the Documentation and Study Centre for the History of Art and Civilization of Ancient Egypt in Cairo. In 1955, it funded a field expedition to document and record the Nubian monuments which would be submerged by the dam’s reservoir waters. Accordingly, the Egyptian Minister for Culture recognized UNESCO as a neutral alternative to other Western political institutions and approached the Director-General for assistance in safeguarding the Nubian monuments (Hassan, 2007).

UNESCO’s response was rapid and the decision to launch a worldwide appeal to protect the Nubian monuments which included the Abu Simbel temples and other archaeological treasures was adopted by the Executive Board of UNESCO at its 55th session. In 1959, UNESCO initiated a public relations and fund-raising campaign, with the support of the Egyptian and Sudanese governments, and collected $40 million from 50 countries to contribute towards the conservation of the monuments. This marked the start of a 20-year campaign to save the temples and an incredible feat of archaeological engineering as the 22 monuments and architectural complexes of the Abu Simbel and Philae temples were taken apart, moved to dry ground more than 60m above their original site, and put back together piece by piece (Figure 1.2) (Berg, 1978).

Figure 1.2 Abu Simbel temples, Egypt (credit: Dennis Jarvis)

The project, coordinated by UNESCO, was regarded as an outstanding success and was remarkable both for the scale of international cooperation and for the interdisciplinary approach which was put in place to save the archaeological heritage. UNESCO established an Executive Committee to lead the international campaign which secured not only funding but equipment and technical expertise from member states. The project mobilized diplomats, fundraisers and patrons as well as experts ranging from Egyptologists and archaeologists, to architects, engineers and geologists. Part of the organizational framework included national committees which were set up in countries as far apart as Japan and Peru to further the campaign. Egypt provided relics and masterpieces of ancient Egyptian art from its state collections to be exhibited abroad to raise funds and increase publicity (UNESCO, 1962). Furthermore, Egypt offered artefacts as gifts to countries that provided support, in fact four Nubian temples were transferred abroad; Dandur to the USA, Taffa to the Netherlands, Dabod to Spain, Ellesiya to Italy, and the Kalabsha gateway to Germany (UNESCO, 2013a). Consequently, the temples have been exhibited in these countries ever since; Dendur in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York; Taffa in the Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden; Dabod in the Parque del Oeste in Madrid; Ellesiya in the Museo Egizio at Turin and the Kalabsha gateway in the Egyptian Museum in Berlin.

Despite the spectacular success of the international campaign to save ‘the heritage of mankind’, nothing could be done to protect the vernacular homes and villages of the Nubian inhabitants of the reservoir area. They were forced to relocate to areas outside their ancestral home and to government-built accommodation (Mohamed, 1980). In an effort to recognize and raise awareness of Nubian history and culture, plans were put in place by UNESCO to establish a museum in Aswan. This was accomplished in 1997, when the Nubia Museum, designed to reflect traditional Nubian architecture, was opened to serve as a focal point for Nubian culture both through its role as a community museum for the Nubian people and as an education point for visitors (UNESCO, 2013b). The museum exhibits a vast number of artefacts that were recovered during the 20-year-long campaign and also acts as a research and documentation centre. However, there was a distinct lack of local capacity to manage and develop the museum and UNESCO together with the International Council of Museums (ICOM) provided training programmes for staff.

The issues surrounding lack of capacity had been more widely revealed by the scarcity of skilled and professional expertise in Egypt to monitor and conserve the newly rescued sites following the cessation and departure of the international campaign. According to the state body responsible for managing the Abu Simbel temples, the Supreme Council of Antiquities, the site is still dependent on UNESCO to supply expertise for training in conservation and management techniques (Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, 2000; Hassan, 2007). The need to develop a regional training centre to provide for long-term monitoring of the Nubian monuments persists. Conservation is thus as much about retaining traditional building skills as retaining the actual monuments. Another outcome of the international campaign was a dramatic increase in tourism. The Abu Simbel temples in particular became a hotspot destination for tourists, no doubt due to the global media coverage of their relocation, and today approximately a million tourists are thought to visit each year (Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities, 2000). The landmark campaign was prophetic in many ways as mass tourism, capacity building for long-term management and the impacts of development continue to be the principal concerns in conserving World Heritage today.

The rescue of the Nubian monuments was followed by several further internationally acclaimed UNESCO campaigns to protect endangered cultural heritage sites, such as the campaign to save Venice and its Lagoon in Italy following disastrous floods in 1966. Following an appeal for aid from the Italian government, UNESCO launched an international operation which brought in major contributions from public and private sources worldwide. The spirit of the campaign is ongoing and UNESCO continues to channel funding for research and preservation, not only of the historic centre of Venice, its monuments and its cultural heritage but also the entire ecosystem of its surrounding lagoon. Further projects were launched in Indonesia and Pakistan in the 1970s and the precedent of international concern for the conservation of universally appreciated heritage had been established.

Towards a heritage of humanity

In 1954, UNESCO launched its first international convention in the field of cultural property protection. The 1954 Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, adopted at The Hague in the Netherlands, was a response to the enormous scale of the destruction of cultural heritage during World War II. States parties to the convention agreed to respect cultural property within their own territory as well as within the territory of other states parties and to avoid inflicting unnecessary damage in conflict situations (UNESCO, 1954, article 4). In 1964, UNESCO put forward a resolution for the creation of the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS), which was adopted at the Second Congress of Architects and Specialists of Historic Buildings held in Venice. ICOMOS was founded in 1965 in Warsaw, following the adoption of the Charter on the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites (Venice Charter), which stipulated the need for international principles to guide conservation. It was formed as a non-governmental organization working towards the promotion and application of theory, methodology and scientific techniques for the conservation of cultural heritage (ICOMOS, 2012). Subsequently, in the late 1960s, the cultural sector of UNESCO together with ICOMOS began to develop a convention to protect the common cultural heritage of humanity. UNESCO’s focus was on the success of its programmes to safeguard the monuments of the world. Initially it did not consider collaboration between its cultural and natural sectors; it would take external influences to promote the concept of linking cultural and natural heritage conservation under the UNESCO umbrella (Batisse & Bolla, 2005).

Emphasis on the global importance of nature conservation came from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (now IUCN), which was one of the few organizations acting internationally in the field of natural heritage at that time. IUCN was struggling to generate funds to meet the challenges of conservation and, in 1961, the World Wildlife Fund was formed. It established a base at IUCN’s headquarters in Morges, Switzerland, and its primary function was to raise funds through international appeals to assist nature conservation societies worldwide. IUCN’s work meanwhile was focused on protected area management and it published the first global list of national parks and reserves in the 1960s. Highlighting the international importance of protected areas, it put out a call for international collaboration on the protection of natural sites (Batisse & Bolla, 2005).

The USA played a pivotal role in establishing the link bet...