![]()

History and

Methods of

Developmental

Psycholog

![]()

| The origins of developmental psychology | 1 |

Defining the subject

Developmental psychology is concerned with the scientific understanding of age-related changes in experience and behaviour. Although most developmental theories have been specifically concerned with children, the ultimate aim is to provide an account of development throughout the lifespan. The task is to discover, describe, and explain how development occurs, from its earliest origins, into adult-hood and old age.

Two strands of explanation are involved in developmental psychology. The discipline takes some of its inspiration from the biology of growth and evolution, but other aspects of explanation are concerned with the ways in which different cultures channel development. Explaining human development not only requires us to understand human nature—because development is a natural phenomenon—but also to consider the diverse effects that a particular society has on the developing child. In truth, development is as much a matter of the child acquiring a culture as it is a process of biological growth. Contemporary theories of development make the connection between nature and culture, albeit with varying emphases and, of course, with varying degrees of success.

This book will examine modern approaches to human development with particular reference to children and their social, physical, and intellectual growth. Intellectual development is concerned with the origins and acquisition of thought and language. This field of study is known as cognitive development and it includes such important abilities as learning to read and write. Problems of cognitive development, for example mental retardation, or the effects of deafness or blindness on the child's understanding, also fall within this domain. Social development is concerned with the integration of the child into the social world, and explaining how the child acquires the values of the family and the wider society.

The balance of the book is towards the traditional study of the childhood years, but we will also introduce modern ideas about development in adulthood. However, most contemporary research concerns the period from birth to adolescence and this is the age range we have covered most extensively. We were concerned to provide adequate coverage of the important recent work on the origins of development and so there is rather more detail on the pre-natal period and infancy than other periods of the lifespan.

It will also become apparent that much contemporary research in cognitive development has been concerned with detailed criticism of the important theory of Jean Piaget, and so his work receives rather extensive critical consideration throughout the book. We also give fairly detailed consideration to the ideas of Lev Vygotsky, who emphasised the importance of social factors in development, and to the work of John Bowlby on establishing social relationships. Wherever possible we introduce evidence from different cultures to illustrate the important principle that human development is both a biological and a cultural process. In a final chapter, we consider how development continues even into adulthood with such important life-events as becoming a parent, moving in and out of employment, and the effects of ageing.

The historical and social background

Human development as a biological process obviously has a long past but its systematic study has a short history. Our need to study development is often motivated by social and economic changes, even though the phenomena of reproduction and growth have always been available for observation.

Western societies did not study the childhood years—from the age of about seven to adolescence—until after the industrial revolution in the nineteenth century, even though early childhood had long been recognised as a distinct period in the life-cycle. Once the social changes in economic organisation induced by the industrial revolution such as population movement from the countryside to the towns were in place, the stage was set for the study of childhood. The industrial revolution led to a need for basic literacy and numeracy in the factories which was eventually to be met by universal primary education. This, in turn, made it important to study the mind of the child so that education itself could become more effective. No doubt other social factors such as increased wealth, better hygiene, and progressive control of childhood diseases also contributed to the focus on childhood.

Adolescence as a distinct stage interposed between childhood and adulthood can also be defined by biological, historical, and cultural changes. The distinctive biological changes of adolescence provide a visible means of demarcation of a further phase in the life-cycle, and this became an object of developmental study in its own right as twentieth-century Western society became wealthy enough to protect the child from adult economic responsibilities. It was possible to postpone the entry of the adolescent into the workforce and also necessary to increase the period of education.

Development in adulthood—lifespan development—is an even more recent object of study. Social and medical changes that have allowed survival into great old age, long after the elderly person has ceased to make a direct economic contribution, have drawn attention to the problems and possibilities of old age. These, in turn, raise questions about the psychology of ageing for the developmentalist to address.

In summary, there are biological and cultural aspects of development at many points in the life-cycle. Biological processes contribute to development and provide “markers” for particular stages. These often acquire significance for reasons of our social history, which provides the impetus to acquire a deeper understanding of the life-cycle. The social structure has an impact on development at all stages of the lifespan. It provides a framework in relation to which distinctive stages, or periods of life, may be identified and studied.

Cultural and biological determinants of development

Present-day developmental psychology is a function of its recent ancestry. Obviously, people have always had children but it is only in the last century that we have moved away from anecdotal descriptions to systematic study of development. “Folk” explanations were very general and often rather prescriptive. For example, the English philosopher, John Locke (1632–1704), thought the child was born a tabula rasa (blank slate), whose every characteristic would be moulded by experience (Locke, 1690). On this view, the newborn is psychologically structureless and extremely malleable to the effects of the environment (Bremner, 1994). Locke's environmentalist view tends to deny that innate factors make any important contribution to psychological development. It places great emphasis on what can be learned as a way of explaining the acquisition of knowl-edge by the child.

In sharp contrast to the views of Locke, the Swiss philosopher, Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), was more inclined to a “natural” theory of human development (Rousseau, 1762). He considered that children are innately “good”, requiring little by way of moral guidance or constraint for normal development, and that they grow according to “nature's plan”. Rousseau's account emphasises “natural” propensities and minimises the effects of upbringing or experience.

Such very general views as those of Locke and Rousseau set the stage for rather misguided debates about the relative contributions of “nature and nurture” to development. Contemporary developmental psychologists avoid such dichotomous approaches to explanation in favour of “interactive” or “dialectical” accounts which attempt more adequately to capture the complex interplay of factors contributing to development.

Scientific foundations of developmental psychology

One of the main differences between a commonsense or folk psychological understanding of development and a scientific understanding is the extent to which theories are subjected to systematic test. Systematic investigations are directed specifically at understanding how, why, and what course human development takes, and this in turn requires rather sophis-ticated methods. Although anecdotal accounts have always been available, and obviously there is folk wisdom in all societies about child rearing, the scientific study of childhood is really very recent. It begins as a serious scientific study in the nineteenth century with Charles Darwin's theory of evolution (see Cairns, 1983).

Foundations: 1859–1914

Charles Darwin is often credited with establishing the scientific approach to developmental psychology. Although his major interests were in evo-lutionary theory, he could be considered the first developmental psychologist because he published a short paper describing the development of his infant son, Doddy, in 1877. He was impressed by the playfulness of his baby son, and by his capacity for emotional expression.

Fig. 1.1 Darwin & his son Doddy. By permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

Darwin's studies of his infant son were intended to help him understand, in particular, the evolution of innate forms of human communication. As we shall see, many basic develop-mental concepts, such as the idea that development can be understood as the progressive adaptation of the child to the environment, can be traced directly to Darwin and the influ-ence of evolutionary theory. Another of Darwin's contributions was to introduce systematic methods to the study of development. The philosophical or anecdotal specu-lations of earlier theorists, such as Locke and Rousseau, were replaced by actual observations of developing children and this set the discipline on a scientific path.

The major biological foundations of developmental psychology were laid in the period between the publication of Darwin's theory of evolution in 1859 and the first decades of the twentieth century. Darwin's theory of evolution located man firmly in nature and raised questions about continuities and discontinuities between man and the animals.

Another effect of the Darwinian revolution was that people became curious about the biological origins of human nature. Evolutionary explanation led naturally to an emphasis on changes that occur as a function of time, both in the extremely long time-scale of evolution and over the individual lifespan. Darwin's books on The origin of the species (1859), The descent of man (1871) and The expression of emotions in men and animals (1872), raised questions about the origins of the human mind in the evolutionary past. They posed the challenging problem of the relation between individual development (ontogeny) and the evolution of the species (phytogeny).

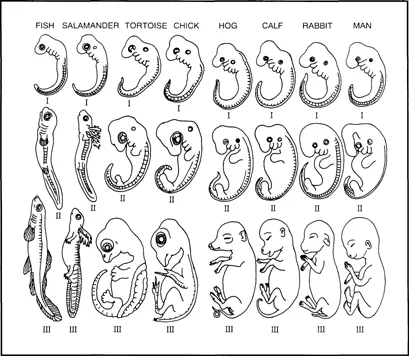

The question of the relation between phylogeny and ontogeny was pursued vigorously by late nineteenth-century embryologists, such as Haeckel (1874), who was impressed by the similar form taken by the embryos of many different species at certain times in their development. Haeckel argued that the development of the human embryo recapitulates its ancestry. The embryo successively takes the shape of various more primitive ancestors, before attaining its final human shape.

Today, it is no longer believed that “ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny” as Haeckel had argued. The more sophisticated view of the resemblances between different mammalian embryos is that the similarities reflect biological structures we still hold in common with our remote ancestors (Gould, 1977). Thus, there is no simple translation from the evolutionary past into present-day development. Nevertheless, clear stage-like changes in biological form led to the idea that other aspects of biological growth, such as cognitive and social development in humans, may also show distinct age-related stages in organisation.

The emergence of an independent developmental psychology is generally dated to 1882, with the publication of a book by the German physiologist, Wilhelm Preyer, entitled The mind of the child. This book was based on Preyer's observations of his own daughter and described her development from birth to two and a half years. Preyer insisted on proper scientific procedures, writing every observation down and noting the emergence of many abilities in his daughter. He was particularly impressed by the importance of the extended period of curiosity evident in human infant development.

Fig. 1.2 Embryos of different species at three comparable stages of development (after Haeckel in Romanes, 1892).

Wilhelm Preyer's work was translated into English in 1888, one of a burgeoning series of publications by then amounting to 48 full-scale empirical studies of children that had been carried out in Europe, Britain, and the United States. Developmental psychology as a discipline was now in full swing.

Among other famous pioneers was Alfre...