eBook - ePub

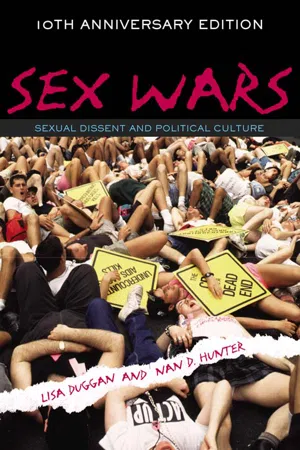

Sex Wars

Sexual Dissent and Political Culture (10th Anniversary Edition)

This is a test

- 360 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is a collection of essays written during the 1980s and 1990s, generated as parts of other, larger activist efforts going on at the time. Read together, the essays trace the progress of the conversations between different activist groups, and between the authors of the pieces, Lisa Duggan and Nan Hunter, creating a bridge between feminists, gay activists, those in politics, and those in the law.

Since the 1995 publication of Sex Wars, the political landscape has altered significantly. Yet the issues (and essays) are still relevant today. The anniversary edition contains a new chapter dealing with the changes in the law since the book's publication (Lawrence v. Texas, for example).

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Sex Wars by Lisa Duggan, Nan D. Hunter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia mondiale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 Contextualizing the Sexuality Debates

A Chronology 1966–2005

Nan D. Hunter

DOI: 10.4324/9781315786728-1

I will love whom I may; I will love for as long or as short a period as I can; I will change this love when the conditions indicate that it ought to be changed; and neither you nor any law you can make shall deter me.—Victoria Woodhull, 1873

Are our girls to be as free to please themselves by indulging in the loveless gratification of every instinct … and passion as our boys?—Frances Willard, 1891

Arguments about the politics of sexuality began in the first wave of feminism and have not ended yet. Throughout the second wave, women have debated questions of power, passion, violence, representation, consent, agency, diversity, and autonomy associated with sex. What follows is a chronology of feminist events and milestones of the last forty years. The specific inclusions and exclusions are idiosyncratic, but the chronology seeks to provide a context and a sense of historical rhythm for the emergence of the ferocious disputes about antipornography laws that seemed to erupt out of nowhere in the early 1980s.

In the chronology, one sees the flowering of grassroots politics in the late 1960s and early 1970s, followed by the migration of debates about sexuality out of obscure movement factionalism into the mass media and the conventional political spheres of referendum campaigns and congressional debates. The core of the feminist debate about pornography occurred during a ten-year bell curve: from the founding of Women Against Violence Against Women in 1976, to the peak intensity generated by the adoption of Andrea Dworkin’s and Catharine MacKinnon’s censorial law in 1984, to the denouement in 1986, when the Supreme Court ruled that law unconstitutional. Beginning with the decline of that issue, in the late 1980s, three new focus points for cultural disputes about sexuality and representation emerge: the controversies over public funding for safe-sex AIDS-prevention programs, the arts funding debate, and the debate over rap music lyrics.

About these three postpornography issues, however, feminists were, for the most part, noticeably silent. Individual women became involved, many as part of lesbian and gay or African American political efforts, but the widespread articulation of a feminist position was largely absent, even when the issues involved invited one. There was virtually no feminist commentary, for example, on the characterization of AIDS as divine punishment for sex. Nor did feminists draw the obvious analogy between the early birth control movement and safe-sex campaigns. Nor was there any visible feminist defense of the claim for a public voice by women, about women’s sexuality, explicit in the work of two of the defunded artists, Karen Finley and Holly Hughes. The bitterness of the internal conflict about pornography disabled most feminists from intervening forcefully in these debates, leaving a crucial perspective largely missing from the conversation. The most significant exception came in the engagement of African-American feminists in the debates over the politics of rap.

Each of these waves of controversy has constituted its own sex panic. Each, reverberating with the others, magnified the sense that the wars over sex and imagery will continue to be fought—inside and outside feminism—for many years to come.

| 1966: | With three hundred charter members, the National Organization for Women (NOW) announces its formation. Its statement of purpose says, in part: “We will protest, and endeavor to change, the false image of women now prevalent in the main media, and in the tests, ceremonies, laws and practices of our major social institutions.” Masters and Johnson publish their clinical findings in Human Sexual Response, documenting that women are multiorgasmic and experience both vaginal and clitoral orgasms, with great variation possible in orgasmic intensity. |

| 1967: | Women active in the New Left press their demands for equality with men in the movement, as well as a political claim that women’s status is analogous to that of colonized peoples in the Third World. Their efforts at both the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) national convention and at a National Conference for New Politics meet with hostility from leftist men. Activist women form groups in Chicago, New York, and Washington, D.C., framing their politics as “women’s liberation.” |

| 1968: | Radical Women in New York protest the Miss America pageant, crowning a live sheep as Miss America and setting up a “freedom trashcan” in which to burn oppressive symbols. A leaflet tells women to bring “bras, girdles, curlers, false eyelashes, wigs and representative issues of Cosmopolitan, Ladies’ Home Journal, Family Circle, etc.” It continues: “Miss America and Playboy’s centerfold are sisters over the skin. To win approval, we must be both sexy and wholesome, delicate but able to cope, demure yet titillatingly bitchy. Deviation of any sort brings, we are told, disaster: ‘You won’t get a man!’” It is a year of tremendous political upheaval. Rebellious students in Mexico are shot by police. Thousands march in France to protest education and labor policies. The Soviet Union quashes a rebellion in Prague by invasion and occupation. In the United States, Dr. Martin Luther King and Senator Robert Kennedy are assassinated. |

| 1969: | On Valentine’s Day, women in New York and San Francisco demonstrate against Bridal Fair expositions. Protesters decry the size of the wedding industry, estimated at five billion dollars a year. Women’s Liberation in New York leaflets the city’s Marriage License Bureau, telling women the “real terms” of the contract they are entering. Marches to repeal abortion laws occur around the country. When police raid a gay bar in Greenwich Village, drag queens refuse to cooperate; the Stonewall Riot marks the beginning of the gay liberation movement. Women demonstrate against Playboy Clubs in Chicago, New York, Boston, and San Francisco. At Grinnell College in Iowa, male and female students stage a “nude-in” when a Playboy representative comes to speak on the “Playboy philosophy.” They demand that he also take off his clothes; he flees. |

| 1970: | It is an extraordinary year for the publication of feminist books: Sexual Politics, by Kate Millet; The Dialectic of Sex, by Shulamith Firestone; Notes from the Second Year, containing Anne Koedt’s “The Myth of the Vaginal Orgasm”; and Sisterhood is Powerful, edited by Robin Morgan, containing such feminist classics as “The Politics of Housework” by Pat Mainardi and “Psychology Constructs the Female” by Naomi Weisstein. Women sit in for eleven hours at the offices of the male editor of Ladies’ Home Journal, winning the right to write and edit a special supplement on women’s liberation that the magazine agrees to publish. The San Francisco Women’s Liberation Front invades a CBS stockholders’ meeting to demand changes in how the network portrays women. Women in the American Newspaper Guild hold a convention on women’s rights. off our backs begins publication in Washington, D.C. An early issue features a spoof called “Mr. April, Playboy of the Month,” and a centerfold ad for “Butterballs,” a male genital deodorant. During a unionization struggle at Grove Press, women occupy the Grove offices and demand equal decision-making power, an end to publications that degrade women, and the use of profits to fund women’s services, including abortion clinics and a bail fund for prostitutes. The President’s Commission on Obscenity and Pornography recommends the repeal of all laws prohibiting the distribution of sexually explicit materials to consenting adults, and the implementation of a massive sex education program. Congress begins a program of federal funding for family planning services. Student protests against the war in Vietnam reach their height with a nationwide strike after violence erupts at Kent State and Jackson State colleges. |

| 1971: | At a Women’s National Abortion Conference, delegates adopt demands for repeal of all abortion laws, no forced sterilizations, and no restrictions on contraceptives, but split on whether to include a demand for “freedom of sexual expression.” That demand is ultimately voted down, and dozens of women walk out. Throughout the movement, the gay-straight split is at its height, as lesbians leave many existing women’s groups to form their own separate organizations. A group of lesbians who leave off our backs begins publication of The Furies. Feminists organize antirape organizations in major cities, beginning with Bay Area Women Against Rape, and the Washington, D.C., rape crisis hotline. Rape crisis centers open around the country, and women use multiple strategies to discredit the myth that “no means yes.” NOW announces a national campaign to change the role and images of women in the broadcasting industry. The NOW Media Task Force is formed, which begins a process of monitoring employment and programming policies at TV stations around the country. During the next five years, NOW files fifteen license renewal challenges against TV stations. The Feminist Women’s Health Center opens in Los Angeles, the first of a series of clinics founded on the principle of self-help and self-examination. The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective publishes the first edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves, a 112-page newsprint book selling for thirty-five cents. |

| 1972: | Ms. magazine begins publication. Shere Hite embarks on a study of women’s sexuality, sending detailed questionnaires on sexual practices and preferences to thousands of women in NOW chapters, abortion rights groups and women’s centers, and asking readers of The Village Voice, Mademoiselle, Brides, Ms., and Oui magazines to participate. The Supreme Court rules that unmarried persons have the same right as married couples to purchase contraceptives. Congress passes the Equal Rights Amendment, sending it to the states for ratification. |

| 1973: | The Supreme Court, in Roe v. Wade, rules that women have a constitutional right to choose abortion. The same year, in Miller v. California, the Court modifies the definition of obscenity to make prosecutions easier. Instead of a requirement the material be “utterly without redeeming social value,” the new test requires proof only that it lack “serious” artistic or social value. Additionally, the Court rules that whether material appeals to “prurient interests” should be judged by local community standards. Chief Justice Burger’s opinion ignores the recommendations of the Presidential Commission (see 1970). African American feminists in New York create the National Black Feminist Organization. Women working in prostitution announce the formation of COYOTE (Call Off Your Old Tired Ethics), an organization urging the repeal of prostitution laws. In New York, Baltimore, and Florida, three women’s presses form: Daughters, Diana, and Naiad. Daughters’ first book is Rubyfruit Jungle. |

| 1974: | The battered women’s movement begins to emerge, influenced by the writings of British feminists; the first shelter for battered women opens in St. Paul. Members of the Beach Cities NOW chapter in Southern California picket the Academy Awards ceremony and demand more leading roles and more nontraditional employment opportunities for women. The first of many lawsuits against major media organizations is filed by women alleging employment discrimination. During the next five years, suits are filed against NBC, the New York Times, Newsday, The Associated Press, the Washington Post, Newsweek, Reader’s Digest, Universal Studios, and many others. Betty Dodson self-publishes Liberating Masturbation after five thousand women respond to a notice in Ms. magazine offering a booklet on women and masturbation. |

| 1975: | Feminist and civil rights groups rally to the defense of Joanne Little, an African American woman from a small North Carolina town who killed a white prison guard in self-defense when he sexually assaulted her. She is tried for murder and acquitted. Against Our Will, Susan Brownmiller’s study of rape, is published. Women in the antirape movement critique race and class bias in Brownmiller’s book and, more generally, throughout the movement. For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf, Ntozake Shange’s anthem of African American women’s voices, opens on the New York stage. The war in Vietnam ends. |

| 1976: | Women Against Violence Against Women (WAVAW) begins in Los Angeles. Members deface a Rolling Stones billboard (“I’m black and blue from the Rolling Stones and I love it”), call a press conference, and Warner Brothers removes the billboard. A conference on violence against women held in San Francisco spawns Women Against Violence in Pornography and the Media (WAVPM). |

| 1977: | In another widely followed case around which feminists organize, Inez Garcia is acquitted of murder for killing the man who held her down while another man raped her. The Combahee River Collective publishes “A Black Feminist Statement,” calling for analysis of “the major systems of oppression” as “interlocking.” Antirape protestors in Pittsburgh organize the first “Take Back the Night” march to dramatize women’s insistence on the right to enjoy public space in safety. Women in Rochester, New York stage civil disobedience at a theater showing Snuff. Snuff protests occur in San Diego, New York, Denver, and other cities. Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum, apparently angered by the increasing availability of Our Bodies, Ourselves in small-town libraries, launches local campaigns to ban the book, claiming that it encourages masturbation, lesbianism, premarital sex, and abortion. In Helena, Montana, the Eagle Forum succeeds in removing the book from school libraries, in part because a local district attorney states that, although it is not legally obscene, librarians who distribute it may be prosecuted for contributing to the delinquency of a minor. The local ACLU sues in federal court to get the book reinstated. |

| 1978: | Events in California illustrate the divergent political tendencies within the movement related to sexual issues. Lesbians and gay men join forces in the “No on 6” campaign to defeat the Briggs Initiative, a right-wing ballot proposal which would have required the state to fire any employee, gay or straight, who advocated gay rights. Various elements within the coalition use different rhetorical and political strategies: gay leftists use the opportunity to defend sexual freedom, while professional campaign consultants obtain an op-ed against the proposal from Ronald Reagan, which becomes the turning point in the campaign. The same year in California, WAVPM organizes a conference on “Feminist Perspectives on Pornography” featuring workshops, speeches and a march by five thousand women demanding an end to pornography. |

| 1979: | Samois, a lesbian S/M group, holds its first public forum at the Old Wives Tales bookstore in San Francisco. Samois criticizes the equation WAVPM makes in its slide show of consensual sadomasochism with violence. Samois later publishes What Color Is Your Handkerchief, which some feminist bookstores refuse to carry, and for which some feminist publications refuse to accept advertising. At the first conference of the National Coalition Against Sexual Assault, a resolution that would commit member groups of the coalition to refuse funding from the Playboy Foundation is defeated; a number of women attending the conference raise six hundred dollars among themselves to repay Playboy’s contribution to the conference. Whether to accept Playboy funding becomes a hot issue for many groups. After an antipornography conference and a march through Times Square modeled on WAVPM’s activities in San Francisco, Women Against Pornography forms in New York and begins leading tours of 42nd Street. WAP advocates education and protest, and specifically disavows censorship. Its position statement on the First Amendment says, in part; “We have not put forth any repressive legislative proposals, and we are not carving out any new exceptions to the First Amendment.” Ellen Willis’ columns in The Village Voice criticize the WAP analysis of porn as simplistic. Andrea Dworkin’s book, Pornography: Men Possessing Women, is published. The Screen Actors Guil... |

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Dedication

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction to the 10th Anniversary Edition of Sex Wars

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Contextualizing the Sexuality Debates A Chronology 1966–2005

- Chapter 2 Censorship in the Name of Feminism

- Section I Sexual Dissent and Representation

- Chapter 3 False Promises Feminist Antipornography Legislation

- Chapter 4 Feminist Historians and Antipornography Campaigns An Overview

- Chapter 5 Sex Panics

- Chapter 6 Banned in the U.S.A. What the Hardwick Ruling Will Mean

- Section II Sexual Dissent and the Law

- 7 Life After Hardwick

- 8 Sexual Dissent and the Family The Sharon Kowalski Case

- 9 Marriage, Law and Gender A Feminist Inquiry

- 10 Identity, Speech and Equality

- Chapter 11 History's Gay Ghetto The Contradictions of Growth in Lesbian and Gay History

- Chapter 12 Making It Perfectly Queer

- Chapter 13 Scholars and Sense

- Chapter 14 Queering the State

- Chapter 15 The Discipline Problem Queer Theory Meets Lesbian and Gay History

- Chapter 16 Lawrence v. Texas as Law and Culture

- Chapter 17 Crossing the Line The Brandon Teena Case and the Social Psychology of Working-Class Resentment

- Chapter 18 Holy Matrimony!

- Chapter 19 Beyond Gay Marriage

- Appendix

- Notes

- Index