eBook - ePub

Tort Law

About this book

This textbook covers the Tort Law option of the A-level law syllabus, and provides at the same time an ideal introduction for anybody coming to the subject for the first time. The book covers all A-level syllabuses/specification requirements, and is written by the examiner in Tort Law for one of the major examination boards. It contains extensive case illustration, and a range of examination related questions and activities. There is a special focus on key skills, and on the new synoptic assessment syllabus requirements. This fully updated third edition builds upon the success of the first two editions, containing a new section on human rights and new case information such as Z v UK, Rees, Walters, Fairchild, Tomlinson, Marcic, Transco, National Blood, Mothercare, Douglas v Hello, Campbell v MGN. fully updated third edition coverage of OCR and AQA specifications, endorsed by OCR for use with Tort Law option includes new OCR synoptic assessment source materials (for use in examinations in June 2005) with additional guidance author is a Principal Examiner for one of the major examination boards new cases include Z v UK, Rees, Walters, Fairchild, Tomlinson, Marcic, Transco, National Blood, Mothercare, Douglas v Hello, Campbell v MGN, with expanded discussion of human rights and new health and safety regulations

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

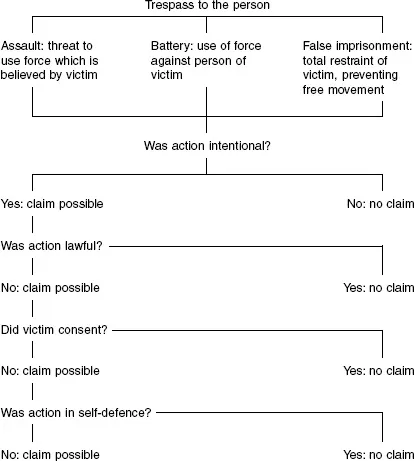

1 Trespass to the person

Trespass is one of the oldest parts of the law and also one of the most important. Trespass to the person gives an individual an enforceable right to bodily integrity and has been a major source of protection of some basic human rights. In effect the tort provides that no person may be threatened with the use of force or touched or imprisoned by someone who does not have either lawful authority or the consent of the victim.

The tort is actionable per se; in other words the victim does not have to prove actual damage or injury, merely the facts which constitute the tortious act. In modern times, the tort has enabled the courts to ensure that police officers and store detectives are liable to pay compensation for unlawful actions. The tort does not always give adequate protection, as will be seen, and Parliament has acted to deal with specific problems. Reference will be made to relevant legislation at appropriate times in the course of this part of the book.

The tort divides itself neatly into three parts – assault, battery and false imprisonment – but some issues, such as consent, are relevant to all three parts. This text will define and explain the individual parts and then deal with the issues which the parts have in common.

The constituent parts

Assault

Definition

The Shorter Oxford Dictionary defines assault as ‘an onset with hostile intent; an attack with blows or weapons’. In the criminal law the word ‘assault’ is used as a general term to cover various crimes against the person. In the law of tort, however, the word has a specific meaning which can be summarised as a threat that force will be used against the victim. A more formal definition is ‘some conduct by the defendant which causes the victim reasonably to fear that force is about to be used upon their person’.

Figure 1.1

Threatening conduct

In many cases the conduct is obviously threatening, for example shaking one’s fist in someone’s face will usually cause that person to fear that a punch is about to be thrown at them. Other factors may be relevant and in some cases have the effect of preventing the action from amounting to an assault.

The physical action may be accompanied by words. These can have the effect of enhancing the threat; for example, ‘I’ll get you for that’ may well make the threat more credible. On the other hand, words can have the effect of negating the threat by making it clear that the threatened use of force will not occur.

Tuberville v Savage (1669)

In this case there was an assault when the perpetrator put his hand on his sword and said, ‘T’were not assize time, I’d not take such language from you’. The victim alleged that he had been in fear that he was about to be attacked with the sword. It was decided that the words used meant that had the judges not been in town on assize, this would indeed have occurred but that as the judges were there, nothing further would happen. There was no assault.

Opinion has been divided as to whether or not words alone can amount to an assault. One old case, Meade’s Case (1823), held that words alone cannot be an assault; more recently, in 1955, a criminal case, R v Wilson, held that they could. The position now appears to be that certainly in relation to criminal law, and therefore almost certainly in relation to the law of tort, threatening words alone can be enough. In R v Ireland (1997) it was held by the House of Lords that a threat made by telephone could be a criminal assault if the victim had reason to believe that the threat would be carried out in the near future – ‘in a minute or two’.

It must be possible for the threatened action to be carried out immediately (Thomas v National Union of Mineworkers [1986]) and, if this is so, it may not matter that others intervene to prevent the threatened action (Stephens v Myers [1830]).

Thomas v NUM (1986)

Mr T was a miner who continued to go to work during a miners’ strike. Mr T and other working miners were ‘bussed’ into work each day through an aggressive crowd of pickets who made violent gestures and shouted threats at those on the bus. The pickets were held back by the police, and in any case Mr T and the others were on the bus. The threats could not be immediately carried out and thus there was no assault against Mr T.

Stephens v Myers (1830)

Mr S was the chair at a meeting which became heated. Mr M became very angry and so disruptive that the people at the meeting voted to turn him out. He said that he would pull Mr S out of the chair rather than be expelled and went towards Mr S with his fist clenched. Others intervened to stop him before he could reach Mr S. The lawyer acting for Mr M said that there could be no assault as Mr M had been unable to carry out the threat, but the witnesses said that he clearly intended to do so had he not been restrained. Mr M was found liable for assault on the basis that he was advancing towards the chairman with the intent of hitting him.

The victim must believe that force will be used

The assailant’s behaviour must lead the victim to believe that force is about to be used against him. This belief must be genuine. This means that, even though there is no requirement that the belief be reasonable in the circumstances, an unreasonable belief is less likely to be thought to be genuine. It is not necessary for the victim to suffer fear or be scared. The point was made in the following case:

R v St George (1840)

An unloaded gun was pointed at the victim. As the victim did not know that the gun was not loaded, the apprehension that he was about to be shot was reasonable – the defendant was found guilty of assault.

Do you think that the law does enough to protect us from threats of violence?

Battery

Definition

‘Battery’ is defined by the Shorter Oxford Dictionary as ‘the action of battering or assailing with blows; … an unlawful attack upon another by beating, etc., including technically the least touching of another’s person or clothes in a menacing manner’. As will be seen, the definition of the tort is in fact very similar. Battery is the direct and intentional application of force to another person.

Touching

The least touch may amount to a battery. There is no requirement that the victim should be injured in any way, so that an unwanted kiss may be enough. Case law gives examples of activities which have been held to amount to a battery. In Pursell v Horn (1838) throwing water over someone’s clothes amounted to a battery; in Nash v Sheen (1953) applying a ‘tone rinse’ to a customer’s hair without permission was a battery.

It must be remembered that the tort is actionable per se so that it is unnecessary to prove that any injury whatsoever has resulted from the touching.

Is hostility necessary?

Everyone is frequently touched in the course of going about daily life, for example when travelling on public transport during the rush-hour. In an old case, Cole v Turner (1704), Holt CJ said that ‘the least touching in anger is a battery’. Where, however, does this leave the unwanted kiss? For some time it was thought that touching is not a battery if it is generally acceptable in the ordinary course of life. This approach was partially rejected by the Court of Appeal in Wilson v Pringle (1987) when it said that battery involves a ‘hostile’ touching, in other words interference to which the victim is known to object.

Wilson v Pringle (1987)

A schoolboy was carrying his bag over his shoulder when it was pulled by the defendant, another schoolboy. The victim fell over and was injured. The judge said that the touching must be hostile and that hostility, which he did not define, could be inferred from the particular circumstances of the case. The pulling in this case was probably only a prank.

It would, however, be impossible for a health care professional to be liable for battery were the element of hostility always required as the usual reason for treatment is to benefit the patient! In such cases, the important issue is whether or not the patient consented to the treatment; if this was not the case then a battery has occurred despite the lack of hostility. F v West Berkshire Health Authority is the leading case on this point.

F v West Berkshire Health Authority (1989)

A mentally impaired woman in her thirties, but with a mental age of four or five, had a sexual relationship and was therefore likely to become pregnant. She was believed to be incapable of coping with childbirth and would be unable to raise a child. She was unable to consent to her sterilisation so the doctors asked the court for help. Held: it was in her best interests to be sterilised.

Make a list of the ways in which you have been touched while going about your daily business and decide which of the touchings could be a battery as defined by the law.

False imprisonment

Definition

The dictionary does not help with this definition. The essence of the tort is that a person has been restrained, whether by arrest, confinement or otherwise, or prevented from leaving any place, by the defendant acting intentionally, without any lawful authority and without the consent of the victim.

Restraint

The restraint must be total. In other words, if there is a reasonable and safe means of escape, the restraint cannot be false imprisonment. Bird v Jones (1845) is the key case here.

Bird v Jones (1845)

The defendants closed off part of Hammersmith Bridge in London so that paying spectators could watch a regatta. The claimant insisted he wanted to go along that part of the bridge and climbed into the enclosure without paying. He was stopped from going forward but told he could go back onto the other part of the bridge where he would be able to cross it on the side away from the enclosure. He refused and remained in the enclosure for half-an-hour. He had an escape route, therefore the defendants were not liable for false imprisonment.

The restraint need not be supported by physical actions or barriers. A police officer who unlawfully tells someone that he is under arrest may be liable for false imprisonment even if the officer does not touch the victim. The victim does not have to take the risk of being forcibly prevented from trying to escape.

False imprisonment can also occur when the victim does not know about the detention! In Meering v Grahame-White Aviation Co. Ltd (1920) Lord Atkin explained this by giving examples of circumstances when it might happen – if the victim is drunk or unconscious. The judge also said that the amount of any damages payable might be less if the victim did not know about the imprisonment.

Meering v Grahame-White Aviation Co Ltd (1920)

Mr M’s employers, the defendants, suspected him of theft. They sent two works policemen to bring him in for questioning. He was taken to a waiting-room where he said that if he was not told why he was there he would leave. He agreed to stay once he was told that enquiries were being made into the disappearance of certain items. Unknown to him, the works police, who had been told not to let him leave the room until the Metropolitan Police arrived, remained outside the room to make sure that he did not leave. Held: restraint within defined bounds which is a restraint in fact, even though the victim does not know about it, may be an imprisonment. Mr M was entitled to damages.

False imprisonment does not happen when the alleged imprisoner imposes ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface to third edition

- Acknowledgements

- Table of legislation

- Table of cases

- Introduction

- 1 Trespass to the person

- 2 Negligence – the duty of care

- 3 Negligence – breach of duty, causation and damage

- 4 Negligence and dangerous premises

- 5 Negligence – defences, remedies and policy issues

- 6 Trespass to land

- 7 Strict liability

- 8 Vicarious liability for the acts of others

- 9 Protecting reputation

- 10 Breach of statutory duty

- 11 Defences and remedies generally

- 12 Tort law in context

- 13 General questions on tort law

- 14 Sources of tort law

- 15 Key skills

- 16 Examinations and assessment

- Appendix: Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms

- Answers guide

- Resources for further study

- Glossary

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Tort Law by Sue Hodge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Law Theory & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.