eBook - ePub

The Rise and Fall of the The Soviet Economy

An Economic History of the USSR 1945 - 1991

This is a test

- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Rise and Fall of the The Soviet Economy

An Economic History of the USSR 1945 - 1991

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Why did the Soviet economic system fall apart? Did the economy simply overreach itself through military spending? Was it the centrally-planned character of Soviet socialism that was at fault? Or did a potentially viable mechanism come apart in Gorbachev's clumsy hands? Does its failure mean that true socialism is never economically viable? The economic dimension is at the very heart of the Russian story in the twentieth century. Economic issues were the cornerstone of soviet ideology and the soviet system, and economic issues brought the whole system crashing down in 1989-91. This book is a record of what happened, and it is also an analysis of the failure of Soviet economics as a concept.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Rise and Fall of the The Soviet Economy by Philip Hanson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

CHAPTER ONE

The Starting Point: the Stalinist Economic

System and the Aftermath of War

The inheritance from the 1930s:

the Soviet economic planning system

The basic institutions of the Soviet economic system took shape in the First Five-Year Plan (1928/29–32). Subsequent modifications were numerous, but not substantial. Basically, the whole economy was run like a single giant corporation – USSR Inc. As corporations go, USSR Inc. was of exceptional workforce size and was a conglomerate with the most extreme range of activities, yet it was run in a more centralised way than most.

The fundamental difference from a market economy was that decisions about what should be produced and in what quantities, and at what prices that output should be sold, were the result of a hierarchical, top-down process culminating in instructions ‘from above’ to all producers; they were not the result of decentralised decisions resulting from interactions between customers and suppliers. Producers were concerned above all to meet targets set by planners. They had no particular reason to concern themselves with the wishes of the users of their products, nor with the activities of competitors. Indeed the concept of competition was absent: other producers in the same line of activity were simply not competitors but fellow-executors of the state plan.

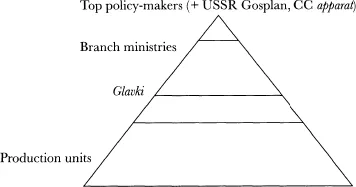

Production was controlled by the state. This control was exercised through a layered hierarchy. The central policy-makers were at the top, like a board of directors. Ultimately these top policy-makers were the Politburo of the Central Committee (CC), the inner ruling group of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). Most of the detail and many important matters of substance were decided by the government or, more precisely, those members of the government with economic portfolios. The Politburo and the government (known for most of our period as the USSR Council of Ministers) overlapped in membership.

These top policy-makers relied on key staff units to make their programmes operational: in particular, the USSR State Planning Committee or USSR Gosplan, and the economic sections of the apparat (administration) of the Central Committee of the CPSU. The name and precise responsibility of the top planning body changed several times within our period, mainly in Stalin’s last years, but for most of the period it was USSR Gosplan.

Reporting to government ministers were the ‘branch ministries’ – the administrative bodies that supervised particular branches of the economy. (The ministries had been known as People’s Commissariats before the Second World War but from 15 March 1946 the bourgeois term ‘ministry’ was adopted.) Typically – and a little confusingly for diplomatic contacts – a branch minister was not a career politician who had been given a particular industrial portfolio, but a manager who had made his (rarely her) career in the industry he now supervised. The Soviet Minister for the Chemical Industry, for example, had more in common professionally with the Chief Executive Officer of ICI or Dupont than with the President of the British Board of Trade or the US Commerce Secretary.

The branch ministries in turn were typically divided into sub-branch administrations, known as glavki (an abbreviation of ‘main administrations’). In some branches of the economy there was also a territorial division, with ‘All-Union’ (USSR-level) ministries replicated at union-republic level: a Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic Ministry of the Coal Industry, for example. Finally, at the base of the pyramid, were all the basic management units in the economy: industrial enterprises, state and collective farms, transport organisations, and so on.

The dimensions of this pyramid (Figure 1.1) were not constant. That is to say, the numbers of branch ministries, glavki and production units were altered from time to time, and the precise composition of the staff bodies at the top also changed. A reasonably representative set of dimensions for much of our period, however, would be as follows: a Politburo of committee size, around 12–14 people; several thousand staff in the central staff bodies; some 50 or so branch ministries, more than a hundred glavki, and close to a million basic production units.

The official description of the economy was that it was a ‘planned, socialist economy’. The words ‘planned’ and ‘socialist’ could mean all sorts of things. What they meant in Soviet practice was the following.

The economy was planned in the sense that the output produced and the inputs used by every farm, industrial enterprise, construction outfit, transport organisation, service enterprise and research unit were governed by instructions from above that were part of a single, national plan. There were annual plans, five-year plans and longer-term ‘perspective’ plans. The annual plans were the most serious operational documents because the national annual plan was made up of obligatory targets and instructions addressed to every production unit – targets that were legally binding. Plans for more than a year were launched with much more public noise, but were less serious. They were by convention identified by their first and final years of operation, so the Fourth Five-Year Plan, for example, was the 1946–50 plan. Outcomes over a five-year plan period usually deviated substantially from plan. The sum of the supposedly component annual plans often differed substantially, too, from the original five-year plan.

Figure 1.1 The Soviet planning system as a layered hierarchy

The economy was socialist in the sense that private enterprise was, with a few small exceptions, banned. Almost all employment was by the state. Every able-bodied person of working age except full-time students and mothers of very small children was required to be employed in a state entity or in a collective farm, or kolkhoz. (The kolkhozy are mentioned separately because nominally they were producer collectives, not state-owned enterprises. State farms, or sovkhozy, on the other hand, were state enterprises.) In practice the collective farms were controlled by the state and not by members of the collective. Their main practical difference from a state workplace was that the members of the collective farm – the kolkhozniki – were not parties to a wage contract with the state; as befitted members of a producer cooperative, they received residual net income from the collective farm’s activity. Since the state controlled their output and non-labour input prices and prescribed targets for their production, it indirectly controlled these residual incomes.

All natural resources belonged to the state. The collective farms officially leased land from the state at zero rent in perpetuity. ‘Productive assets’, that is, the fixed assets of production units other than (nominally) the collective farms, all belonged to the state. Private assets could legally take the form of household contents, houses (chiefly in rural areas and on the fringes of cities; most urban housing belonged to the state), cars, holdings of cash and accounts in the state savings bank, plus the occasional issues of state bonds, the purchase of which was, typically, compulsory.

The planning system covered the state production establishment: that is to say, all the state entities and the collective farms. There were four components of economic activity that were not subject to obligatory annual plan instructions.

First, for most of our period, there was a labour market of sorts. People were not sent under compulsory plan instructions to work at this or that enterprise. They could and did change jobs of their own volition. There were exceptions: prisoners, of course; members of the CPSU (around a tenth of the adult population), who could be directed as a Party obligation to work at particular places but seldom were; and young people graduating from higher and further educational establishments, who were in principle directed to work at particular workplaces for two years after graduation. Some direction of labour continued to be on the statute books for a short time after the Second World War. By and large, however, there was a market relationship between the state as employer and the household sector as a provider of labour services. People needed to be induced by pecuniary and non-pecuniary benefits to work at any particular workplace.

Second, for most of our period households were not allocated rations by the planners but bought what they themselves chose to buy – out of what the state made available. So consumption, like the supply of labour, entailed a market relationship between households and the state production establishment. The market concerned was neither flexible nor competitive. Officially, and for most purposes in reality too, the state production establishment was the sole supplier, and it fixed both prices and the quantities of each item supplied. Unlike the monopolist of the economics textbook, the planners did not fix quantities and let prices adjust, or fix prices and let quantities adjust; they fixed both. The planners lacked both the information and the motivation to fix prices and quantities so that markets cleared. Therefore queues, shortages and occasional surpluses prevailed at established prices for many consumer goods and services.

Third, the Soviet state could not directly plan what foreign partners would buy from it or at what prices they would sell to it. It could plan what would be made available for export and in what quantities, and what it would seek to buy; but it was again obliged to operate on a market basis with foreign trade partners. This was certainly the case in Soviet trade with the West and, on the whole, with developing countries as well. It was less clearly the case in Soviet trade with fellow-members of the Soviet-dominated trading bloc, the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA). Even there, however, planning was never effectively supranational, and outcomes depended on inter-state bargaining.

The fourth area where the plan was not in any direct sense the determinant of what happened was the Soviet private sector. This was a mixture of legal, grey- and black-market activity, whose overall size cannot be determined with great confidence. The use by rural and suburban households of small household plots of land was highly regulated and, for part of the period, taxed, and peasants were required to make some deliveries from their plots to the state, but the household plots were legal and not directly planned. For much of our period the ‘private plots’ produced about a quarter of the Soviet food supply. Much of this was subsistence production: in other words, the food produced on the plot was consumed by the household itself. But some was sold on so-called kolkhoz markets. These were regulated but, for most of our period, the prices on them were not directly controlled by the state, and could and did fluctuate as supply and demand conditions altered.

That was the main legal element of private economic activity. There was also a grey area of spare-time repair work by skilled workers or tuition by teachers, whose legal status was never made entirely clear. This grey economy was an area in which ingenuity flourished. When a new block of apartments was fitted out, for example, by a state building trust, one scam was to hang all the doors the wrong way round; the building trust workers would then visit the new occupiers and offer to put things right privately, at a price. Notoriously, medical staff in hospitals often had to be bribed to look after patients properly. By the time the Soviet Union collapsed, there was almost no service that was not susceptible to this kind of corruption.

In the arts, several activities, such as painting and sculpture, were not easily conducted on anything but a freelance basis. Paintings, for instance, were from Khrushchev’s time quite freely sold to private patrons at mutually agreed prices. Here the state’s main means of control was through admission to the official union of painters (or writers or illustrators or actors). Only practitioners licensed in this way could legally work solely in their chosen field. Anyone who was not in the painters’ union, for instance, had no right to a studio and had to have a day job.

Then there was the outright black economy, covering the resale of goods stolen from state sources, extortion, the running of prostitutes, the illegal distilling of vodka and other criminal activities.

In the 1970s and 1980s value added in the private sector (legal plus semilegal plus illegal) may have amounted to around 10 per cent of Soviet GDP. Estimates are discussed later on in this book. The great bulk of production, therefore, really was socialist and planned. State plans were comprehensive, so they necessarily included plans for household consumption, labour supply and foreign trade, but these were not administratively controlled by the state.

The central planning system was a remarkable arrangement. The most remarkable thing about it is that it worked, in the sense that the Soviet economy was for more than half a century a going concern, with output increasing and unemployment minimal. (Officially, the Soviet Union had no unemployment at all. There was therefore no such thing as unemployment benefit. In fact, there was some unemployment, but it was very small.) When one reflects that this system rested on detailed annual instructions to a million or so production units in all sectors of the economy, about the production of perhaps 20 million distinct goods and services, the fact that it functioned at all is impressive. There is no answer to the question, how many different goods and services are produced in a country. The level of disaggregation is almost infinitely adjustable: are ‘shoes’ a product, or men’s shoes, or men’s brown brogues, or men’s brown brogues size 9, and so on? In the 1960s and 1970s, however, several Soviet commentators referred to a product assortment divided into some 20 million categories, and we can take that as a measure of the range of goods and services that entered into the reckoning of planners and producers, even if much of the planning was done at a more aggregated level.

Who were the recipients of plan instructions? The number var...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgements

- Editorial Foreword

- Introduction

- 1. The Starting Point: the Stalinist Economic System and the Aftermath of War

- 2. Khrushchev: Hope Rewarded, 1953–60

- 3. Khrushchev: Things Fall Apart, 1960–64

- 4. A New Start: Brezhnev, 1964–73

- 5. The ‘Era of Stagnation’: 1973–82

- 6. Three Funerals and a Coronation: November 1982 to March 1985

- 7. Gorbachev and Catastroika

- 8. The End-game, 1989–91

- 9. The Soviet Economy in Retrospect

- Bibliography

- Index