eBook - ePub

Western Europe

Geographical Perspectives

This is a test

- 312 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Western Europe provides a balanced appraisal of common characteristics and shared problems of the eighteen states lying to the west of the former Iron Curtain.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Western Europe by Hugh Clout,Mark (Reader In Geography, University Of Exeter) Blacksell,Russell (Professor Of Geography, University Of Sussex) King,David (Professor Of Economic Geography, University Of Plymouth) Pinder in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1

Optimism and uncertainty

Fundamental features

More attention has been devoted by geographers to Europe than to any similarly sized portion of the earth’s surface. Generations of scholars have described and analysed its diverse natural environment, the numerous human activities that it sustains and the complex imprints that they impart to its evolving cultural landscapes. Research monographs, textbooks and learned articles, replete with maps and statistical series, record these facts and interpretations in every language in use across the continent. The majority of these works are expressed at the scale of the state, the region or the precise locality; only rarely do authors look to wider horizons and try to capture the fundamental essence of Europe (Mellor and Smith 1979; Hoffman 1989).

Long and intimate knowledge of the continent and penetrating understanding of the minds of its geographers enabled W. R. Mead (1982) to produce such a distillation in a challenging and wide-ranging essay entitled ‘The discovery of Europe’. It is his belief that the distinctiveness of Europe as a whole derives from an amalgam of physical geography, ethnography, technology, values and territorial organization. The physical resource base of this continent of peninsulas, isthmuses and islands, stretching from Mediterranean latitudes to beyond the Arctic Circle, is intricate and remarkably diverse, with localized resources often complementing those available in neighbouring areas. The assembled interdigitation of land and sea, successions of mountains, plains and valleys, arrays of soils, and gradations from maritime to continental climatic regimes are without parallel.

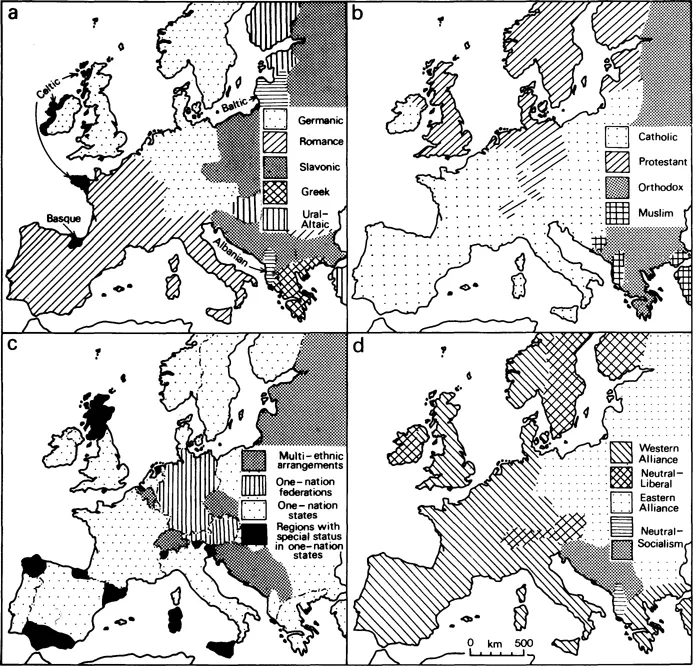

Nowhere else in the world is there comparable cultural complexity across such a relatively compact area, whether this is expressed with regard to tangible features, such as traditional house styles or field patterns, or in terms of language or religious tradition (Fig. 1.1). In this respect, sharp lines on maps must be recognized as deceptive, since significant minority groups are to be found within apparently homogeneous cultural domains. Migration flows during many centuries have produced far more complicated meshes of language and religious tradition than Fig. 1.1 could possibly convey, with the recent arrival of migrants from North Africa, Asia and many other distant parts of the world providing striking examples.

For two centuries, Western Europe was the focus of technological innovation, cradling the Industrial Revolution, diffusing technical skills throughout the world, and experiencing the emergence of post-industrial civilization more intensely than elsewhere. West Europeans flourished by virtue of their technical acumen and commercial expertise, with several nations amassing great empires by land or sea. The fruits of technology, colonialism and trade added even more advantages to those enjoyed by the dwellers of this already well-endowed part of the globe. Imperialism and commerce ensured that methods and techniques developed in Western Europe were adopted widely throughout the world. The same processes contributed to the diffusion of shared European values, including inventiveness and democracy.

In addition, Western Europe bears the distinctiveness of an intense proliferation of states of varying ethno-political status, ranging from one-nation federations (such as Austria and Germany) and multi-ethnic units (such as Belgium and Switzerland) to one-nation states (such as France and Italy) (Fig. 1.1c). However, several one-nation states contain areas with autonomous status (e.g. Alto Adige, Sardinia, Sicily and the Val d’Aosta in Italy) or with special status with regard to bilingualism (e.g. Friesland in the Netherlands) or legal system (e.g. Scotland in the UK). Western Europe’s states and their boundaries have undergone complex evolution through time, with the territorial imperative being at the heart of hundreds of the continent’s wars, including the two world wars of our own century. Europe has a more elaborate patchwork of political boundaries and national ‘systems’ of administration and organization of ordinary life than any other continent (Jenkins 1986).

Fig. 1.1

Cultural indicators: (a) language groups; (b) religious tradition; (c) ethno-political situation; (d) political blocs pre-1989.

Cultural indicators: (a) language groups; (b) religious tradition; (c) ethno-political situation; (d) political blocs pre-1989.

Nationality implies peripherality as well as centrality and Western Europe is endowed with areas of marginality along all of its political boundaries. For four and a half decades after the Second World War none of these was sharper or harsher than the line that partitioned states and component regions of the old continent, stretching from the Atlantic to the Urals, into two fundamental blocs: the Eastern and Western alliances, with relatively few countries maintaining neutral positions (Fig. 1.1d) (Wallace 1990). Of course, the East/West divide was not impervious; Western travellers and tourists visited Eastern Europe but significantly fewer East Europeans travelled westwards. Radio and television programmes transmitted in West Germany and Austria reached substantial parts of East Germany, Czechoslovakia, Hungary and Yugoslavia, while Western radio programmes were received much further eastward, and continue to be so. None the less, in many respects, the ‘real division of Europe’ was between territories that looked ultimately to Moscow or to Washington DC and it was given most acute expression along the line of the ‘Iron Curtain’, regardless of whether that was composed of brick, concrete, barbed wire or minefield (Fontaine 1971; Ritter and Hajdu 1989). Twelve of the chapters of this book concern themselves with economic and social conditions in the states located to the west of that critical line and with the lives of the Europeans who inhabit them. The focus of the final chapter is shifted to the ‘new Europe’ that is fast emerging.

Seen from the global perspective, Western Europe is composed of a set of ‘old’, predominantly urbanized and industrialized nations which are served by dense networks of transport and communication (Jordan 1973). Indeed, the population of Western Europe is older than that of any other continent. In Germany there are already more than four pensioners for every ten workers; by the year 2030 their numbers may well be almost equal. West Europeans are rich, well fed (even over fed) and well educated. They live long, healthy and relatively comfortable lives, and display low levels of natural increase. Their agricultural systems are highly productive, regularly generating ‘mountains’ of surplus butter, grain and fruit and ‘lakes’ of surplus milk and wine which could relieve the suffering of the world’s under-fed millions.

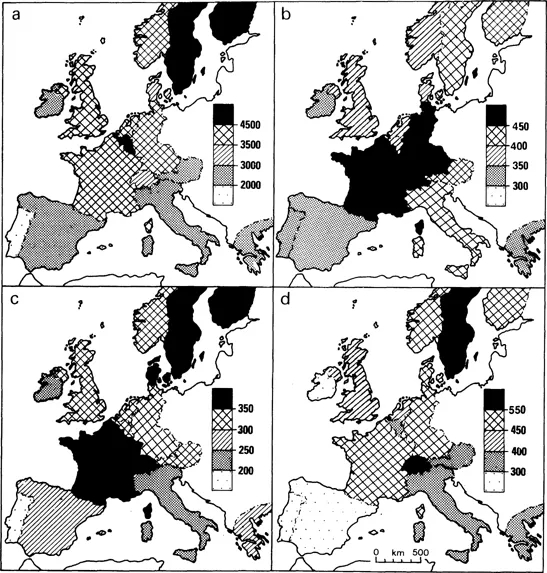

Fig. 1.2

Indicators of well-being: (a) consumption of energy (tonnes of oil equivalent per capita), 1988; (b) motorcars per thousand population, 1988; (c) television sets per thousand population, 1988; (d) telephones per thousand population, 1988.

Indicators of well-being: (a) consumption of energy (tonnes of oil equivalent per capita), 1988; (b) motorcars per thousand population, 1988; (c) television sets per thousand population, 1988; (d) telephones per thousand population, 1988.

While acknowledging the general validity of this array of facts and perceptions, the mythical ‘average’ West European would insist that attention be drawn to at least three major qualifications. First, the countries to the west of the long-taken-for-granted East/West divide through Europe display important spatial differences with regard to the affluence and well-being of their inhabitants (libery 1986). Such features emerge clearly from analyses of per capita income, energy consumption, housing quality, health care, car ownership and a host of other indicators (Fig. 1.2).

The broad dimensions of these differences are well known, with an affluent West European ‘core’ contrasting with a poorer Atlantic and Mediterranean ‘periphery’ (libery 1984).

Second, these differences are simply spatially packaged expressions of social differences with regard to employment, class and access to financial resources, educational capital and political power. ‘Regional problems’ do not exist of themselves, in splendid spatial isolation; they are just geographical expressions of more deeply rooted social conditions which have grown in each specific political economy (Massey 1979). In Western Europe, they cannot be divorced from the working of capitalism in the late twentieth century, while in Eastern Europe they reflect the painful recent espousal of capitalist principles (Carney, Hudson and Lewis 1980; Peet 1980; Williams 1987).

Third, many of the indicators that defined the strength and general well-being of Western Europe in the eyes of the world underwent a drastic reversal in recent years. The 1950s and 1960s had been a period of unprecedented economic growth and political stability and West Europeans had been swept along in a tide of rising expectations, generally believing that they would enjoy even greater affluence in the years to come (Landes 1969). In the past two decades, such assumptions have become redundant. Widely accepted facts of economic strength have become fables and commonly held principles of economic supremacy have been converted into problems. After a protracted phase of optimism, West Europeans entered a time of disillusionment and uncertainty about their economic future. By the late 1980s increasingly harmonious relations between Washington and Moscow, coupled with reform and largely peaceful revolution beyond the ‘Iron Curtain’, lessened many old fears, but the fragmentation of the former USSR and of Yugoslavia raises new economic and political uncertainties for the future.

Changing conditions

In many ways the world is no longer as Eurocentric as it was earlier in the twentieth century. In terms of global strategy, Europe was effectively divided between the Communist East and the capitalist West for over four decades, with policy decisions taken in the USSR and in the USA being of ultimate significance for all its inhabitants. Since the Second World War, decolonization has brought independence to the territories that made up the empires of Belgium, France, the Netherlands, Portugal and the UK, although in many instances significant contacts with respect to trade, aid and education still survive. European culture is probably less distinctive than in the past since the continent has become increasingly open to the rest of the world and the Western countries are in the shadow of a partner and protector of vast size and unprecedented economic and cultural importance, namely the USA.

In the economic context, multinational corporations, often based in North America or the Far East, have come to exercise control of numerous branches of manufacturing and business life in Western Europe (Lee and Ogden 1976). In very many respects, the dominating influence in each West European country during many of the post-war years was that of the USA, rather than that of another European country or of Europe as a whole (Aron 1964). However, the completion of the Single European Market of the EC at the end of 1992 may impart more of a unified (West) European image to the wider world. Dramatic changes in the world energy market since the end of 1973 drove home even more forcibly the fact that West European nations were no longer the masters of their own destinies. As Sampson (1968) had stressed just a few years earlier, Europe was more than ever at the mercy of events, discoveries and decisions outside its frontiers. The decision by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) members to abandon price-fixing arrangements with international oil corporations brought the era of cheap oil to an end. Crude oil prices tripled immediately and world-wide inflation began its dizzy course, ultimately producing recession in Western Europe and elsewhere in the oil-importing world.

After a phase of recovery following the Second World War and a remarkable period of low-cost growth in the 1950s and 1960s, the economies of Western Europe were thrown into a condition of depression and decline after 1970. Taken-for-granted confidence in their economic strength, resilience and adaptability was shaken to the very roots (Dicken and Lloyd 1981). Firms went bankrupt by the hundreds of thousand and manufacturing plants have been closed in vast numbers. Deindustrialization was not matched by a comparable expansion of jobs in other sectors and hence many once-strong regions and areas of the economy have entered the ranks of the depressed (Johnston and Gardiner 1991; Martin and Rowthorn 1986).

Western Europe is now set in a context of remarkably low demographic growth and some countries and regions recorded more deaths than births during certain years in the past decade. Fewer children are being born but West Europeans are living longer and the growing requirements of the retired population are making new and quite necessary calls on public-sector finances for pensions, housing, health care and other services. European attitudes to the concept of the family are changing, with high divorce rates and increasing numbers of single-parent families creating a new magnitude of social strain. With the decline of work prospects and the end of decolonization, the volume of immigration to Western Europe has declined substantially by comparison with the peak years of the 1960s; indeed, attempts have been made by several reception countries to redirect labour migrants back home and the threat of repatriation gives rise to profound political concern. The presence of so many ‘new Europeans’ has introduced a striking measure of cultural diversity to many areas with, for example, Islam becoming an important new component in the religious complexion of Western Europe (Trébous 1980). To some extent the countries of the West have already become significantly multicultural, but this ongoing process continues to be surrounded by serious social tensions which have their most painful expressions in inner-city environments and post-war housing estates. The recent arrival of large numbers of asylum-seekers, refugees and ‘ethnic Germans’ has created new strains in many regions.

It may be argued that West Europeans have become more politically conscious than in earlier decades and certainly there is an increasing trend for all aspects of planning and public administration to be enveloped in political challenge and debate. A growing number of people are expressing their concern for social justice and are attempting to exercise their political muscle in order to change the distribution of scarce resources to the benefit of those in need. Concern for the rights (actual or claimed) of specific sectors of society and for regional minority groups is being expressed more forcefully and sometimes violently. The rise of ‘green’ political parties, whose aims are imbued with the principles of ecology and conservation, reflects a growing concern for the world at large; and the critical moral issues surrounding the use of nuclear energy and the possession of nuclear deterrents are receiving wider public debate than ever before. A worrying new feature has been the rise of far-right political groups in many countries, whose members preach the dangerous message of national and ethnic ‘purity’.

In the 1990s, Western Europe finds itself in the apparently paradoxical situation of becoming both more united and more fragmented at the same time. The EC enlarged from six original signatories of the Treaty of Rome (1957) to twelve member states, with Turkey havin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Optimism and uncertainty

- 2 Political evolution

- 3 Demographic and social change

- 4 Migration

- 5 Energy

- 6 Industry

- 7 The service sector

- 8 Urban development

- 9 Agriculture and rural change

- 10 Recreation and conservation

- 11 The encircling seas

- 12 Trends in regional development

- 13 Western Europe and the ‘new Europe’

- References

- Index