![]()

1

The elements and temperaments

Introduction

Gathering in front of a fireplace on a cold winter’s evening, smelling the freshly turned earth in springtime, relaxing on a porch feeling a cool summer’s breeze move across your face, lying in a hot bath when you are not feeling well, or experiencing utter wonder from a rainbow or shooting star, gives us direct experiences of what some ancient cultures referred to as the “elements.” These interactions are all activated by our senses, often producing profound and sensual experiences. Direct connections to these elements are usually accompanied by deeper kinds of emotional responses and spiritual understandings. With more and more people living indoors with urbanized lives, there are fewer opportunities to experience both incidental and direct connections to nature. However, with more deliberate designs, architecture and the urban context within which they exist, can foster greater exposure to the positive benefits of the elements. These elements have been observed by and have been of interest to our ancestors for millennia, and are now referred to as the “classical elements.”

Today, however, when we speak of the elements, we are either referring to the elements of the Periodic Table or outside environmental conditions, especially inclement or severe weather.1 One is constantly made aware of the negative effects of the elements through frequent news of natural disasters throughout the world. From 1900 through 2016, the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology Database (CATDAT) has reported that there have been over 35,000 natural disaster events globally. Approximately a third have been caused by flooding, a quarter by earthquakes, and a fifth by storms, and about one percent by volcanic eruptions. Over eight million deaths have occurred as a result of these disasters.2 It is clear that hazard reduction and emergency management should be of major concern in the planning and design of the built environment.

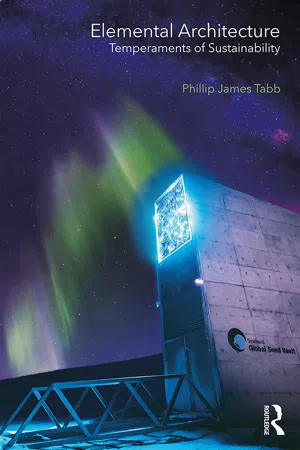

Beyond the obvious responses to the disastrous powers of the elements, there have been ways of experiencing nature with attendant sustainable and positive healing effects that have evolved throughout our history. In addition, there are mysterious and fascinating qualities that now are again being recognized as being present and important. They not only express through the individual elements, but through their combined effects as well. Many of these kinds of advantages have been studied. Benefits to physical health, improved cognitive performance, and psychological well-being have received much more attention than the social or spiritual benefits of interacting with nature, despite the potential for important consequences arising from the latter. Important now is the goal to promote the positive benefits of interactions with nature and the elements in a rapidly urbanizing world. A central theme in this book is to create a re-enchantment with source experiences, particularly those fostered by the elements. To Laura Hobgood and Whitney Bauman, the elements constitute our very existence and are the sources from which we emerge, and the elements toward which we will return.3 (Figure 1.1 is a photograph of a Seaside, Florida pavilion designed by architects Jersey Devils. It is perfect place positioned for viewing sunsets and the beach, and listening to the sounds of the surf, while accompanied by ocean breezes.)

FIGURE 1.1 The Natural Elements

(Source: Phillip Tabb)

Origins of the elements

The origin of the elements is inextricably linked to our understanding of the known universe. And life, as we know it, occurs within certain conditions that define our earthly existence. Early concepts explaining the nature of our material world were often thought to be based on four to five substances, referred to as the “elements.” These elements were proposed to describe material types, attributes, and energetic qualities. Varying ancient cultures ascribed differing phenomena and cosmologies to these sets of elements, yet there were remarkable similarities. The four classical or terrestrial elements, each originally conceived as the unique, arché, “beginning,” “principle,” or “original substances,” were independently proposed by early pre-Socratic philosophers: water, by Thales; air, by Anaximenes; earth, by Xenophanes, and fire, by Heraclitus. And, Anaximenes is also credited with the principal element ether, which he called the “boundless.”4

Sicilian philosopher Empedocles (c. 450 bc) was a disciple of Pythagoras and Parmenides and was credited with the combination or mixture of the four elements of fire, earth, air, and water, calling them the four roots. Later, Aristotle (c. 384–322 bc) added a fifth element: ether or aether that was considered the material that filled the region of the universe, and would most likely, not being occupied by the four earthly elements. These four terrestrial elements had the tendency to change and move in random patterns, while ether was observed to move on a circular motion. To the medieval alchemists, quintessence, quinta essential, is the Latin name for the fifth element.5 It represented the most perfect embodiment of the substances, which was also related to essence, soul and spirit as well as the mysteries associated with the cosmos. In medieval philosophy, it also signified that which permeates all of nature. In Greek mythology, ether was referred to as fresh air or clear sky.

Mnemosyne in Greek mythology was considered the mother of the nine muses and goddess of memory. Fathered by Zeus, the muses were Calliope (epic poetry), Clio (history), Euterpe (music), Erato (lyric poetry), Melpomene (tragedy), Polyhymnia (hymns), Terpsichore (dance), Thalia (comedy) and Urania (astronomy). And according to Clive Knight in a series of monotypes, these nine muses were related to breathing (air), nourishing (earth), sleeping, cleansing (water), procreating (fire), resisting gravity (earth), communicating (air), and aging and dying (ether).6 This classification has certain associations with the elements.

According to Titus Burckhardt, the quinta essential was expressed in the seal of Solomon, where individual parts of the symbol were represented geometrically by the four elements. An upward-pointing equilateral triangle represented fire, a downward-pointing triangle was water, an upturned triangle with a horizontal bar two-thirds of the way up represented air, and a downturned triangle with a bar represented earth. When superimposed upon one another, they formed the six-pointed star or seal of Solomon.7 These symbols of the five elements can be seen in Figure 1.2. Ether in this set of symbols assumes the sign of the seal of Solomon with the overlapping triangles as a synthesis of the terrestrial elements. Another symbol was the equal-armed cross with earth at the north, fire at the south, air to the west, and water to the east, with ether in the center crossing. This particular four-fold symbol was known as the “peaceful cross” or the “equal-armed cross,” and eventually encircled, became the astronomical symbol for the Earth. In certain traditions, this later symbol resulted in the associations of the elements with specific directions and seasons: fire – south/summer, earth – north/winter, air – west/autumn, and water – east/spring.

FIGURE 1.2 Symbols of the Five Classical Elements

(Source: Phillip Tabb)

The elements and the qualities they possess are still considered today. According to Joanne Stroud, “The images drawn from [the ancient Greeks’] divinely-inspired mythology became an enduring allegorical yardstick by which western cultural history is still being measured.”8 This set of elements was considered the fundamental substances of the physical world, a hierarchical model of the cosmos, and the temperament traits of personality. Similar categories of the elements were present in other ancient cultures even though their attributes widely varied. Egypt, Babylonia, Japan, Tibet, Korea, and China each evolved basic elements as reduced observable substances constituting the material world. In Babylonia, for example, the elements were perceived as four gods personified by the sea, earth, sky, and wind. Similarly, in Egypt, the early Three Element Theory was based on Heliopolis’ creation myth (3100 bc) in which water (primal waters or Nun), earth (land and horizon or Geb), and fire (sun or Ra) formed a model of the universe. Ra was the sun god who ruled all parts of the created world: the sky, earth, and underworld. Air (moisture or Shu) was then added. Shu was a primordial Egyptian god of emptiness. Later, ether was added. Together, they became what is central to the formation of human beings. According to Robert Lawlor, Nun was the cosmic ocean representing pure undifferentiated spirit-space.9

In India and Hinduism in particular, the elements were associated with the five senses and were agents or mediums for the sensual experiences enabled by each sense: fire which can be seen, earth can be experienced by all the senses, air can only be felt and heard, water can be felt, seen, heard, and tasted, and ether can only be sensed by hearing as it was experienced beyond the other senses. Fire, agni in Sanskrit, was the source of warmth and illumination. Earth, brahma, was a solidifying element. Air, called prana, sustained life through breath. Water, apas, was thought to be the lifeline of human existence, and was considered vital to maintain hygiene and cleanliness. And ether, akasha, meaning in Sanskrit “to be seen,” was the first of the great elements, and therefore, was the essence and subtlest of all the material world. In Buddhist phenomenology, it is divided into either limited space or infinite space.10

In China, there were five elements, which were known as the Wu Xing, and they differed slightly from the Greek ones. Wu Xing is a verb, literally meaning “to act.” The Wu Xing described elements, phases, movements, and processes of change. The Chinese saw them as continuous patterns of transformation. They became the five elements theory where substances were divided into five specific elements: wood, fire, earth, metal, and water, and were originally derived from the ancient divination text, the I-Ching or Book of Changes (1000–750 bc).11 These elements later became formative processes in the practice of Feng Shui or Chinese geomancy. Each of the elements was associated with fathering certain actions ...