![]()

SECTION VII

Surgery for congenital heart disease

![]()

39

The anatomy of congenital cardiac malformations

ROBERT H. ANDERSON AND DIANE E. SPICER

INTRODUCTION

Knowledge of detailed cardiac anatomy is a prerequisite for successful surgery. Nowhere is this more important than in the setting of congenital cardiac malformations. Although the anatomy displayed in these anomalies is often complex, it is not necessarily difficult to understand. In this chapter, we describe the basic rules of cardiac anatomy, which permit the surgeon, working in the operating room, to diagnose and recognize the arrangement of the cardiac chambers. As we will show, this knowledge, at the same time, will provide guidelines to the position of the vital conduction tissues. The basic layout of the heart should, of course, be established prior to commencement of intracardiac procedures. The diagnosis of even the most complex cases demands, in the first instance, no more than the distinction, in terms of morphology, of a right atrium from a left atrium, a right ventricle from a left ventricle, and an aorta from a pulmonary trunk. Distinction of these various chambers and vessels then provides the basis of the approach for simple sequential segmental analysis. The anatomy of “holes” and “stenoses” and so on are of equal, or even greater, significance. This morphology will be described in the appropriate chapters. Here we are concerned specifically with setting the ground rules for a systematic approach to cardiac anatomy.

APPROACHES TO THE HEART

When usually arranged, the heart lies in the mediastinum, with its apex pointing to the left and two-thirds of its bulk to the left of the midline. An unusual location of the heart should alert the surgeon to the possibility of complex malformations, although these are not always present when the heart is abnormally located. If abnormally positioned, we find it best to describe this finding in simple terms, such as heart mostly in the right chest with the apex pointing to the left, or as appropriate. Whatever its position, the heart and its great vessels can be approached either through the midline anteriorly or via the thoracic cavities.

A median sternotomy is used most frequently. The anterior mediastinum immediately behind the sternum is devoid of vital structures. This tissue plane is reached through separate incisions in the suprasternal notch and beneath the xiphoid process, the two being joined by blunt dissection.

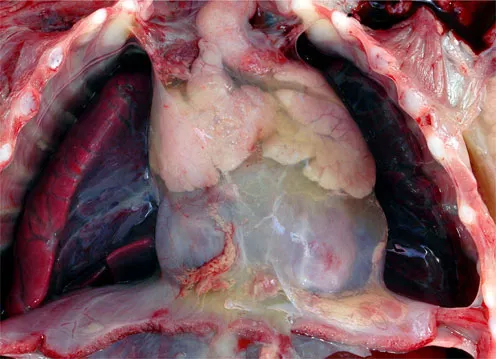

Splitting the sternum will expose the pericardial sac, seen between the pleural cavities (Figure 39.1). In the infant, an important structure in this region is the thymus gland, which wraps itself over the anterolateral aspects of the pericardium in the area of the arterial pole. The gland itself is made up of two lateral lobes joined by a midline isthmus, which sometimes must be divided or partially excised to provide adequate exposure. Care must be taken with its arterial supply from the internal thoracic and inferior thyroid arteries. If divided, these arteries may retract beneath the sternum and produce troublesome bleeding. The thymic veins are also a potential problem, being fragile structures which often empty via a common trunk to the left brachiocephalic vein. This vein may be inadvertently damaged by undue traction.

Once the pericardium is exposed via a median sternotomy, access to the heart poses few problems. The vagus and phrenic nerves traverse the length of the pericardium well clear of the operative field, with the phrenic nerves anterior, and the vagus nerves posterior, to the lung hilums. The phrenic nerves may be vulnerable when the pericardium is harvested for use as an intracardiac patch or baffle. Excessive traction on the fibrous pericardium should be avoided, since this can avulse the origin of the pericardiacophrenic arteries, which accompany the phrenic nerves. The internal thoracic arteries themselves should not be at risk during exposure of the heart via a median sternotomy, but they may be damaged when the incision is closed.

39.1

Lateral thoracotomies provide exposure either to the heart or to the great vessels via the pleural spaces. Most frequently, these incisions are made in the fourth intercostal space, using the posterior bloodless triangle between the edges of the latissimus dorsi, trapezius, and the teres major muscles. The floor of this triangle is the sixth space, but division of the latissimus posteriorly, together with serratus anteriorly, frees the scapula and provides access to the fourth space, which is identified by counting from above. An incision midway between the ribs avoids the intercostal neurovascular bundle, which is protected beneath the lower margin of the fourth rib. Having entered the pleural space on the left side, retraction of the lung posteriorly exposes the middle mediastinum, with the left thymic lobe overlying the pericardium and the aortic arch with its associated nerves and vessels. If access is needed to the heart, this is usually achieved anterior to the phrenic nerve. More frequently, the aortic isthmus and descending aorta are approached and then the lung is retracted anteriorly, the parietal pleura being divided on its medial aspect posterior to the vagus nerve.

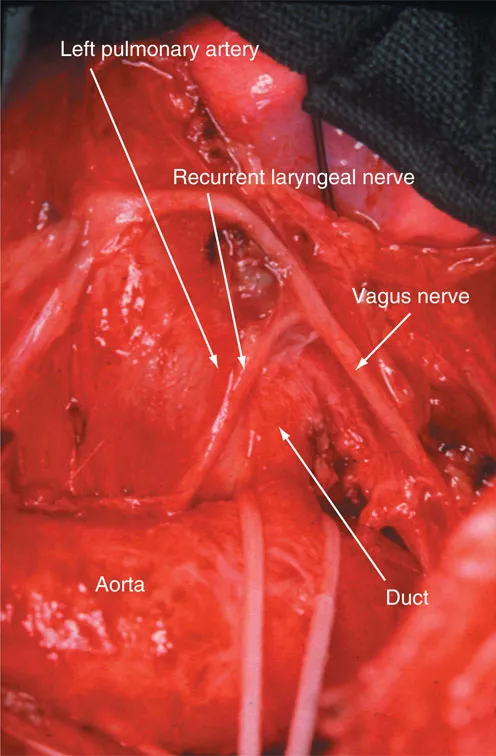

An important structure in this area is the left recurrent laryngeal nerve (Figure 39.2). This nerve takes origin from the vagus and curves round the inferior border of the arterial ligament, or duct if still patent. Excessive traction to the vagus can cause injury to this structure just as readily as direct trauma in the environs of the ligament. The thoracic duct ascends through this area to drain into the left jugular vein at its junction with the internal jugular vein. Accessory lymph channels draining into the duct can be troublesome when dissecting the origin of the left subclavian artery.

A right thoracotomy is performed in similar fashion, reaching the heart via the fifth interspace or the right-sided great vessels through the fourth interspace. When approaching the right pulmonary artery, it is sometimes useful to divide the azygos vein near its junction with the superior caval vein. On the right side, the recurrent laryngeal nerve passes round the subclavian artery as it courses medially from the vagus towards the larynx. Also encircling the artery on this side is the subclavian loop from the sympathetic trunk. Damage to this structure can result in Horner’s syndrome.

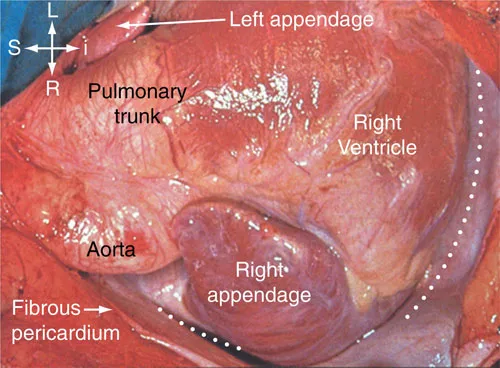

Surface anatomy of the heart

Opening the pericardial cavity reveals the surface of the heart, which almost always is mostly in the left hemithorax with its apex pointing to the left. Important and readily recognizable landmarks enable the nature of the cardiac chambers to be determined with considerable accuracy by external inspection (Figure 39.3). Attention should first be directed to the atrial appendages. These anterolateral outpouchings from the atrial chambers usually clasp the arterial pedicle. The finding of both appendages on the same side of the pedicle is itself an anomaly – so-called juxtaposition of the atrial appendages. Left-sided juxtaposition is almost always associated with abnormal connections of the cardiac segments, but right-sided juxtaposition, whilst much rarer, tends to be found with relatively simple malformations such as atrial septal defect. Juxtaposition in itself is a nuisance to the surgeon, since it will necessitate alterations in planning the cannulation, and so on. Juxtaposition can also markedly distort the architecture of atrial anatomy, and can produce problems unless properly recognized. Once recognized, nonetheless, the problems are readily surmountable.

39.2

39.3

39.4a

39.4b

39.4c

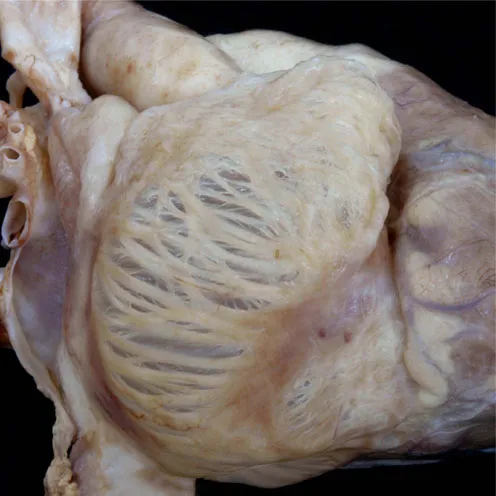

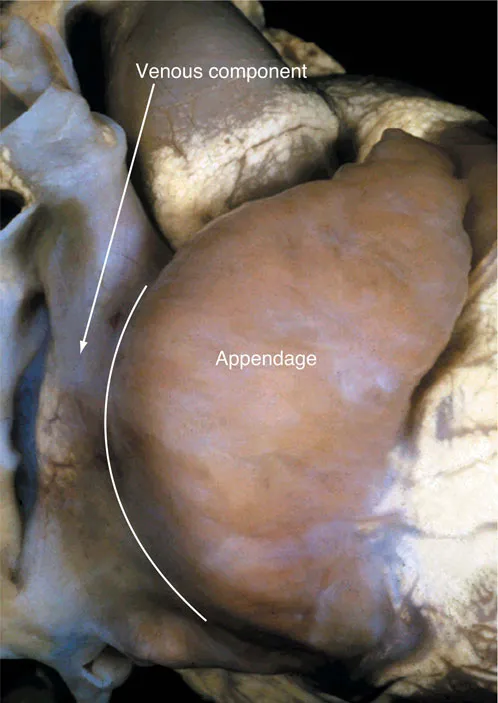

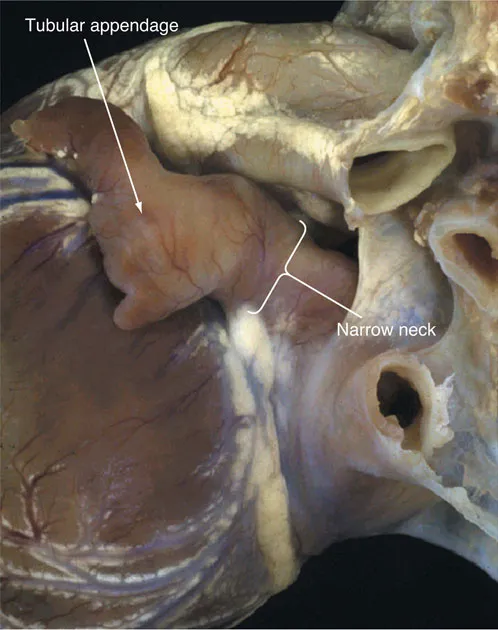

Having established the position of the appendages, the next step is to establish their morphological nature. When the terms “right” and “left” are used in this chapter, they are used to indicate morphology rather than position. Where position is also abnormal, this situation will be indicated separately. Differences in the shape of the appendage are usually sufficient to permit the surgeon to distinguish the morphologically right from the morphologically left atrium, with the pectinate right appendage having a triangular shape (Figure 39.4) in contrast to the tubular left appendage (Figure 39.4c). The most reliable means of distinguishing between the appendages, however, is to examine the nature of their junctions with the remainder of the atrial chambers. It is often not appreciated that the entire anterior wall of the right atrium, as seen by the surgeon, is made up of the pectinate wall of the appendage. Thus, the pectinate muscles in the triangular morphologically right appendage extend to the crux of the heart, encircling the vestibule of the tricuspid valve. In contrast, the morphologically left atrioventricular junction is smooth, containing as it does the coronary sinus, and with the pectinate muscles confined within the anterosuperiorly located tubular appendage. These dif...