![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction

It is difficult to resist comparing progress in social psychological explanation with that in the natural sciences. Few social psychologists would agree that their work has resulted in the same accumulation of predictive successes and coherent theory as has occurred in fields such as physics, chemistry, or biology. As for comparing the success of social psychology with other subfields of psychology such as personality, behavior theory, or developmental psychology, they are all so integrally related that the result may not be worth the effort.

There are at least two levels at which dissatisfaction with the pace of progress in social psychology has occurred during the years since World War II. At the empirical level, methodological issues of the sort contained under the rubric of artifacts in experimental design is one such set of problems, and the place of the experiment itself as the principal tool in developing social psychological theory is the principle problem at the epistemological level. Both levels are addressed throughout the course of this book.

There has always been a controversy surrounding the use of objective methods, particularly the scientific experiment, in answering questions about complex human processes such as social interaction and, in the past, consciousness itself, however defined (e.g., James, 1962; Lashley, 1923). As early as 1890 William James was wary of the use of experiments to explain complex human behavior. He believed that the deterministic assumption, best served by experimental analysis, is merely provisional and methodological and that the assumption of determinism is therefore open to discussion on a level other than the scientific. He understood that a psychologist who wishes to build a science must at least tacitly take the deterministic position. However, the psychologist does not, therefore, have to believe that all human characteristics are explainable by deterministic, scientific methods.

John Watson’s (1913) shift in emphasis from the study of the contents of consciousness to the study of behavior, championed direct observation over the previous dependence on introspection practiced by 19th-century psychologists. Watson, against the study of consciousness per se, developed his argument against the validity of introspection as the principal method of psychology. The introspective analysis of consciousness had yielded a great deal of controversy. The laboratories of different investigators produced different conclusions about the same phenomenon depending on the theoretical bias of the psychologist. Discrepancies were essentially uncheckable because they depended on the introspection of the trained observers of each of the laboratories. There was no agreed upon basis by which hypotheses could be tested.

Watson’s idea that behavior had to be the data of psychology required the additional assumption that the sense data of the observer of behavior was the key element in the process. What the observer could see, hear, smell, and so forth, could be confirmed by another observer and consensus could easily be reached regarding the nature of the data under examination. This, in turn, meant that the controlled experiment could become the principal method of the behaviorist. Watson was careful to indicate that this approach did not eliminate the fact of either the presence or absence of consciousness, which was, by definition, unobservable.

Karl Lashley (1923), working 10 years after Watson’s position was initially published, held that science, defined as the examination of sense data via an objective method such as the experiment, is not appropriate for an examination of felt experience and, therefore, of consciousness. Later, Lashley, Tolman (1927), and Hull (1943), although not denying its existence, were also to exclude consciousness from the possibility of fruitful examination by the methods of science.

Despite those reservations concerning the use of experiment to answer questions about complicated human functions by some of the leading psychologists of the early part of the century, Carl Iver Hovland and his associates (Hovland, Janis, & Kelley, 1953; Hovland, Lumsdaine, & Sheffield, 1949) launched postwar experimental social psychology with his persuasion experiments while gathering about him many disciples who were to become the country’s leading exponents of experiment applied to social problems. From 1945 until the mid-1960s, we worked diligently on discovering the details of how people formed and changed their attitudes, beliefs, and opinions, and how, or if, behavior followed, and how it could be changed in a good cause. It became clear during the 1960s that many conclusions could not be supported by research from other laboratories or from our own replication. The study of attitudes, beliefs, opinions, and the persuasive process then experienced the same reduction of generalizability of results and the accompanying narrowing of experimental focus that other experimental efforts (e.g., those of Clark L. Hull) suffered in the late 1940s. It was in the 1960s that a number of social psychological experimenters began discovering crucial difficulties in their experimental procedures. These difficulties were not of the usual variety, involving calibrations of various kinds or changes in procedure in order to better elicit a response from the subject. Rather, social psychologists discovered that the subject entered into the experimental procedure in a way that had not been expected. In an experiment, variation in the subject is either controlled directly by the experimenter by manipulation of the relevant independent variables or is presumed to vary randomly over a number of subjects. Difficulty arose when some of those uncontrolled variables that were thought to vary randomly, were responses from the subject directed toward being in the experiment itself. In short, by interpreting various aspects of his or her participation in an experiment, the subject introduced a confounding variable that rendered the results of the study either meaningless or grossly distorted. Sufficient interest in these distorting variables was generated to produce a body of research on artifacts in social psychological experimentation. This research was summarized and discussed by a number of involved social psychologists in Robert Rosenthal and Ralph Rosnow’s now well-known Artifact in Behavioral Research, which appeared in 1969. The suspiciousness of the subject of the experimenter’s intent, whether or not a subject had volunteered to appear in a study, whether or not a pretest was used to evaluate some characteristic of the subject before an experimental treatment was applied, what the subject believes is required of him or her in an experiment, what the subject believes the experimenter expects of him, and whether the subject is anxious about participating in an experiment, all appeared as factors that could distort the meaning of the experimental results. In the decade of the 1970s, research continued on artifacts in the experimental process, further refining the nature of the difficulties more often than eliminating them. Since the late 1960s, social psychologists have had a choice; they could continue to perform experiments in order to eventually minimize or eliminate the effects of unwanted subject influence in the social psychological experiment, or they could concentrate on the very nature of the experiment itself and its place in a field that purported to discover information on the nature of social existence. One could also, of course, do both, but with separate efforts. This crisis in social psychology has been well documented (e.g., Rosnow, 1981) and we need not deal with it here. What I prefer to focus on is the progress that has been made in the field since the late 1960s, progress that has largely taken the two avenues already suggested. In the late 1980s we have become both more empirically astute and epistemologically more sophisticated than we were 20 years ago. Controversy still abounds, but of course it would and should in a field with intelligent, energetic practitioners.

In the 20 years that have elapsed since the first edition of this work, there have not been startlingly new theoretical successes based on experimental research in social psychology compared with success in, for example, biology with its discovery of the DNA molecule. There has been interesting new work in social psychology (e.g., Altman’s, 1976, fusion of the physical environment with social arrangements, Nisbett and Ross’, 1980, attribution of causality as a social judgment) but the accumulation of useful predictions about social phenomena has not kept pace with the successes of the natural sciences by any means, although there are different rates of success among physics, chemistry, and biology. Assuming social psychologists are as intelligent, resourceful, and creative on the whole as natural scientists, and I have no reason to doubt that they are not, it is imperative that we discover the factors that account for the different rates of success of social psychology compared with those of the natural sciences.

Social psychologists know how to do an experiment. They understand the logic of the process and are as resourceful and creative as any other scientist in designing an empirical test of a hypothesis. I am convinced that our lack of significant progress compared with that of the natural scientists is not based upon technical or logical failures as experimenters. It is based instead on the nature of our defined subject matter and the way we conceive the nature of our problems. The questions we ask and the solutions that are logically and technically feasible need to be carefully delineated. We have been discussing various epistemological aspects of social psychology over the past 20 years. Many of the controversies that have arisen can now be resolved. Many of us will continue to do experiments and others will concentrate on epistemological issues; that is the way it should be in a healthy field. However, one epistemological possibility is that there may be logical limitations to answering certain questions about the nature of the human socius through experimental methods. Other questions can only be answered by experimental analysis. I attempt to separate the two here.

Finally, some explanations, particularly those that seem incomplete, may nevertheless satisfy some people more than others who insist on the apparent finality of the development of a scientific law. What kind of explanation we are satisfied with as social psychologists is also at issue and is discussed in later chapters.

THE EMPIRICAL FOCUS OF THE PAST 20 YEARS

Perhaps the single best record of change and development in social psychological methods and theories since the late 1960s is Lindzey and Aronson’s 1985 edition of The Handbook of Social Psychology. The two volumes of the handbook contain reviews of the experimental and theoretical efforts of social psychologists in all of the major subareas of the field, thus there is no need for such reviews to be presented here. However, I discuss some of the material regarding attitude to illustrate certain changes in the practice of social psychology.

William McGuire (1985), in his excellent chapter on attitudes and attitude change, has identified certain historical periods where interest ran high in how attitudes change, and what procedures one may use to change them. In the first period, that of Pericles 500 years before the birth of Christ, the art of persuasion was conceived to be the mastering of one or another set of principles of rhetoric. The second period ends with the demise of Cicero in 43 B.C. and again depends on oratorical principles. Rhetoric and hermeneutics were also the subject of 15th-and 16th-century orators who flourished in the liberal period of the Italian Renaissance. McGuire placed the fourth period of intense interest in persuasion and attitudes from the 18th century to the current, with emphasis on the late 19th to 20th centuries as a result of the industrial revolution and its attendant interest in the distribution of large numbers of new goods, and the accompanying changes in customs and social beliefs that inevitably followed.

It is the change in approach between the first, second, and third persuasion eras on the one hand, and the fourth period on the other, which is of central significance to some of the changes that occurred in the empirical and theoretical pursuit of answers to social psychological problems during the past 20 years of our own era. The Greek, Roman, and Italian periods of approach to attitude and persuasion were rhetorical in nature, whereas the modern period beginning in the 18th century and continuing to today, is positivistic in the broadest sense. We see in later chapters that the rhetorical form, under different guise, has been reintroduced into both the lexicon of social psychological theorizing as well as into the conceptual characterization of social psychological problems of all sorts, including those involving attitudes and persuasion. (See chapter 6 on Hermeneutics and Rhetoric.)

Attitude Change and Persuasion

The concept of attitude is so central to many general ideas of social existence that the theories developed to explain how people form attitudes and the applications that are drawn from these theories are reflected in many other theoretical areas within social psychology in particular and psychology in general. This centrality of the concept of attitude, however defined, has been both a focal point for research and theory as well as a target to be attacked by social psychologists on the verge of developing a different paradigm. The assumptions involving theory development or empirical approach that sometimes precedes theory is of particular interest.

Attitude research reflects social psychologist’s concern about the informational exchange they may expect from the results of an experiment on an individual’s functioning in groups, real or symbolic. Although the original question raised in the mid-1960s concerned the issue of whether experiments on attitudes were of any use whatsoever (Lana, 1969, 1976), the accumulated 20 years of thinking on the matter allows us to frame the problem differently. The question now is, “Under what circumstances and for what purposes may a traditional laboratory experiment be reasonably able to answer our questions about the formation and change of attitudes, and when must we move to field studies, environmental examinations or other forms of in situ observations to answer our questions?” In addition, certain questions asked about attitude require concepts more typical of traditional sociology with its concern with institutions, ideological phenomena on a mass scale and, ultimately, the history of a group, than of social psychology.

There is still a mélange of methods accompanying almost as many theories in attitude research now as in 1969. The difference now is that researchers are more aware of the place of their methodology and of their theory within the layers of explanation that are possible for the phenomenon we call attitude and all its manifestations. In 1975, Fishbein and Ajzen still speak of the myriad working definitions of attitude that are used by researchers and theorists of various stripes. Clearly no agreement has been reached in defining terms, yet I am convinced that progress of a sort has been made.

If we concentrate for a moment on the apparent inability of social psychologists to agree on a working definition of attitude, we may conclude that the difficulty lies with the complexity of the phenomenon they are examining and with the difficulty of manipulating attitudinal variables by the usual experimental methods. Why is this so? One reason is that the very definition of attitude always refers to an integrated process in the human being, such as disposition to respond in a certain manner to an identifiable class of objects, or McGuire’s “responses that locate objects of thought on dimensions of judgment.” Integrated processes do not easily lend themselves to conceptual dissection. Whatever the operational or conceptual definition, and literally hundreds have been counted (Fishbein & Ajzen, 1972), consistent predictions of attitude responses over even the same situations have never been found by any researcher. There are always major exceptions. Consistent predictions of specific responses in even restricted situations are hardly ever accomplished. What has been accomplished over the past 20 years is the development of a richer, more sophisticated picture of human decision making when the objects and processes about which decisions are made are social.

N. H. Anderson’s (1981) integration theory is one of the more successful attempts both to explain responses attributable to attitudes, and to place attitudes within a broader range of social psychological phenomena. The nature of this success is of critical importance for understanding the quality of explanation in social psychology and its similarities and differences to the natural sciences.

Anderson’s contention is that multiple causation is responsible for all thought and behavior. These causal factors result in an integration of information available to the individual from which context he or she makes decisions regarding attitudes and beliefs, and behaviors associated with them. Anderson made an implicit distinction between thought and behavior, an issue to be discussed in its own right later in the book. An attitude can be analyzed by applying algebraic models to the thought that precedes human judgments and decisions.

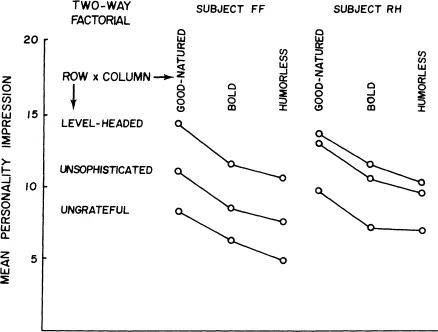

In summarizing many years of research on impression formation, Anderson demonstrated a certain consistency in these judgments. The parallelism hypothesis that demonstrates this consistency is illustrated in Fig. 1.1. Subjects were asked to describe people labeled “level headed,” “unsophisticated,” and “ungrateful” by selecting adjectives such as “good,” “bold,” or “humorless” to describe them.

The parallel curves indicate that there is no significant interaction effect and hence Anderson concludes that an averaging model best describes the subject’s behavior. The rating response is linear. That is, each adjective has the same meaning and value regardless of what other adjective it is paired with in personal description. A further implication of the parallelism hypothesis is that the meaning of adjectives used to describe people is constant so far as the value of the adjectives to an observer. Anderson contrasted this conclusion to Asch’s (1946), where personal adjectives were assumed to change meaning depending on other adjectives with which they were paired. Anderson pointed out that Asch relied heavily on introspective interpretation on the part of his subjects, and that Asch’s results were the products of a semantic illusion dissipated by the experimental results cited previously.

FIG. 1.1. Anderson’s parallel theory data. Judgments of likableness of persons described by pairs of personality-trait adjectives. The observed parallelism supports the averaging model of person perception. (Data after Anderson, 1962. Copyright © 1974.)

Anderson’s careful research over the past 20-odd years is both consistent and impressive. It represents one of the best continuing research programs in contemporary social psychological research. For our purposes, it is useful to contrast Anderson’s research process and results with a similar program in one of the traditional natural sciences.

The work by Maurice Wilkins on X-ray diffraction pictures of the DNA molecule that preceded Crick and Watson’s (Watson, 1968) model building of its structure, is one of the most significant scientific developments of the 20th century. The biochemical experiments that it spawned changed the nature of the way biologists and chemists operate. Before Crick and Watson’s solution, crystallography and its resultant X-rays of DNA had yielded significant information about the nature of genetic material. Crick and Watson’s problem was largely theoretical—to build a model of the DNA molecule based on structural hypotheses in turn inspired by the existing empirical evidence available in X-ray pictures. Their task was essentially to discover the shape of an existing molecular structure in terms of the arrangement of various atoms within it. Because the molecular structure in question was considered to be the basic genetic material of animal matter, the implications for the discovery are far ranging both for theory and for practical matters in medicine, organic chemistry, and a great many other areas.

Once the double helical structure of DNA was discovered, everyone ...