![]()

Black Blood Red to Palest Pink

![]()

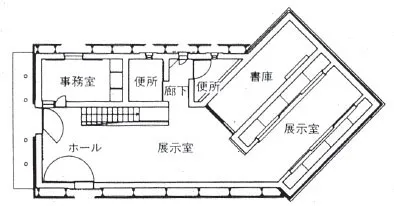

1.1 Tucked away in Nagano Prefecture, Terunobu Fujimori’s 1992 Jinchokan Moriya Historical Museum was his debut work.

1

Neolithic Daddy

Terunobu Fujimori

Is pleasure not the province of architecture?

—Paul Finch1

Even in Japan, Terunobu Fujimori’s structures are oddities: buildings balance on crooked legs, stumps driven directly into soggy soil; lumpy plaster walls crazed in a filigree of fine cracks; weeds sprout from buildings’ skins.2 Inside his 1991 debut structure, Jinchokan Moriya Museum, is a capriciously inaccessible tower (for building storage) reached by a drawbridge. Associates, who knew Fujimori as a respected historian, assumed this first building was an architectural aberration. Emboldened, Fujimori’s subsequent structures were instead odder: his second was an awkward, over-heavy lump speckled with tiny, fragile flowers and topped with a pyramidal lawn. Fujimori’s designs emerge as if from illustrations in a child’s book: tree-trunk columns in a forest-like interior, playful teahouses punningly close to tree houses, a valiant bush topping Camellia Castle. “Soda Pop Spa,” for nude bathing, wears dapper stripes of scorched cedar and white plaster. Each architectural effort is entirely unique and idiosyncratic. Fujimori once impishly insisted, “Someday I would like to make something like Gaudi’s out of wood …”3 Outlandish, Fujimori’s architecture is also in demand, his tiny structures often published in the professional press or exhibited alongside far more complex masterpieces by Toyo Ito, Arata Isozaki and other major architects.

Fujimori himself is something of an outlier. A historian specializing in Japanese architecture of the late nineteenth century, he only began to design buildings in his middle age. He argues that today

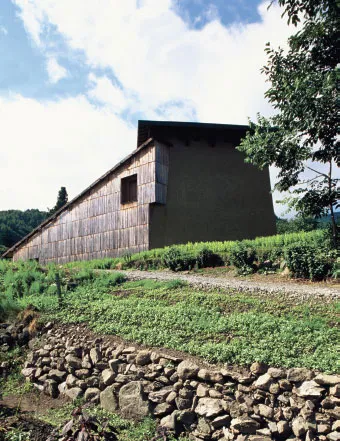

1.2

1.2 Long, hand-split cedar shakes, evidence of a lost art, meet a stucco coat applied with gouged blocks of styrofoam.

“… I find the act of conceiving and building … to be immensely rewarding, since the act of practicing architecture gives life to the knowledge I have gained as a historian.”4 Managing no more than a handful of structures in any given year, Fujimori is an award-winning provocateur.

His architecture invokes built tradition without being slavish. He mixes vernacular references with inspiration from the early days of Modernism, especially its unexplored opportunities. While avant-garde architect Toyo Ito worried, “… that Fujimori-style architecture pretty much repudiates all of Modernism is vexing,” Fujimori corrected Ito, arguing, “[I] collect the dregs and things that twentieth-century modernism threw off, and draw them together.”5 Alvar Aalto’s architecture might be thought an exemplar for the kind of Modernism that influences Fujimori, progressive and place-specific.6 Other heterodox Modernist examples include Mies van der Rohe’s low-slung brick buildings or the postwar architecture of Louis Kahn – rough construction and modest materials making up a sensually and symbolically rich Modernism, works of wood, brick, or stone, the familiar materials of the world around us.

Fujimori says of his approach, “In my architectural vocabulary there are many ties to older farmhouses. It’s like putting together an original language derived from the fragmented words of various rural nooks and niches.”7 His building blocks are playfully altered in their incorporation. Odd elements of construction are used as punctuation marks, snagging the eye and calling attention to the way his architecture quotes the commonplace, yet also challenging you to recollect their roots. In an early essay, architect Kengo Kuma called Fujimori’s work “Nostalgia like nothing you’ve ever seen.”8

Especially inspired by Le Corbusier, Fujimori underscores,

… completing the Villa Savoye served as a consummation; after that [Le Corbusier’s] style made a turn: from orthogonal boxes to rugged, sculpted form, from a white, flat wall to rough unfinished concrete surfaces. No longer only steel, glass, and concrete – natural stone, red brick, timber, earth.9

This is the hedonic Le Corbusier, the one pictured pot-bellied and naked at a cabin, whose architecture emerged through observation and opportunities to build in India and rural France.10 This was Le Corbusier mourning “The destruction of regional cultures …” arguing “… what was held most sacred has fallen: tradition, the legacy of ancestors, local thinking …”11

Le Corbusier – like the early twentieth-century Tokyo architect Antonin Raymond, who was once accused of stealing from Le Corbusier’s sketchbooks and who in turn influenced Fujimori – dispensed a rough regionalism where geography or use demanded: at the 1930 Errazuriz House in South America, for example, or the 1935 La Palmyre-Les Mathes cottage, a summer retreat built in the impoverished inter-war era. Of Errazuriz House, scholar Christiane Crasemann Collins suggested, “… Le Corbusier chose native tree trunks, plainly notched … In its artless simplicity, the timber of the interior is the most overt gesture toward the ‘primitive hut,’ more so than the rustic stones and clay tiles.”12 She goes on to quote Le Corbusier:

Since sufficiently skilled labor was not available in this place, the composition was developed using elements existing on the site and easy to build with: walls of big blocks of stone, roof-frame of tree trunks, roof of local tiles, therefore a sloping roof.13

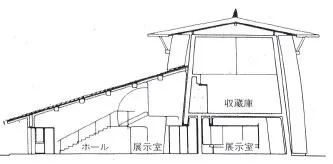

1.3

1.4

1.5

1.6

1.7

1.8

1.9

1.3-9 The entrance is framed in slender trunks culled from the slopes above the site; oddly intriguing details throughout, many reflecting Fujimori’s naïveté, enliven the simple structure.

1.11

In these later, postwar projects, Le Corbusier’s architecture is voluptuous, tactile and coarse, not the streamlined sophistication inspired by ships.

Other important architects operating outside mainstream practice in Japan also trace their education and training directly to Le Corbusier, most through Takamasa Yoshizaka, who worked in Le Corbusier’s office from 1950–1952; projects on the boards at that time included Ronchamp, Chandigarh, and the Villa Shodan in Ahmadabad, India. Again at home, Yoshizaka designed the 1956 Japanese Pavilion for the Venice Biennale, unglazed openings interrupting roof and floor; the pinkish, presciently postmodern 1962 Athène Français, an exterior sporting letters incised in scalloped concrete;14 and the 1965 University Seminar House, tiny huts scattered across a slope, an enormous inverted pyramid piercing the summit above. Yoshizaka joined Waseda, an illustrious private university, in 1959; while there, he taught many idiosyncratic architects to be discussed later in this book: Osamu Ishiyama, Hiroshi Naito, and the founders of the ateliers of Team Zoo, each embracing architectures rough and rooted. Fujimori sets his work, and theirs, in opposition to the convention of internationally-oriented architectures, which he calls a “White School” with a purist bent: spare structures, state-of-the art, smooth and swooping, scholarly and scientific.15 Its antithesis, which Fujimori colors Red, inclines instead to rough and rugged, robust and vigorous, intending an ongoing evolution of traditional artisanship and even of artless ineptitude.

Fujimori’s lively and even audacious humor distance...