EMPIRICAL EVIDENCE suggests that many environmentally oriented public procurement programmes have underachieved because of less than optimal implementation. The failure to take into account existing procurement practices, purchase authority delegation, and oversights in programme management, organisation and motivation are among the reasons for poor results. This chapter illustrates three factors that play an important role in the implementation of green public procurement programmes:

The chapter is based on an earlier study made by the author for the OECD (Pento 1997) and a new collection of empirical data on the procurement of goods and adoption of environmental programmes in public organisations in Finland.

Decision-Making Units and Procurement Inertia

A government’s policy decision to purchase only environmentally preferable goods does not guarantee that the current direction of procurement will be changed. The decision-making units (DMUs) that are authorised to make purchasing decisions are independent and may not follow the adopted policy. A DMU may consist of only one person, as is the case when a department secretary orders more copying paper. Multiple-person DMUs are common when the purchase is of a higher value or when a product is purchased either for the first time or for a longer time-period. A large DMU may consist of buyers, managers responsible for budgets, users of the product, experts on purchasing and contracts, technical specialists, and nowadays also environmental experts. All members of the DMU may have disincentives—imagined or real—against choosing green products.

The functionality of green products may be a concern. For example, the decision to buy recycled copying paper may raise difficulties with the members of the DMU if the new paper does not perform as well as the old paper. Some recycled paper has generated negative user experience, because it causes dust to collect in high-speed copying machines, or jams laser printers. If it is likely or even possible that the members of the DMU will be criticised for their selection of a green product, it is easier for them to continue to purchase the same product as before.

Secondly, existing user preferences and habits work against switching to green products. An air-blower in a toilet may be better for the environment than paper towels, but if the users strongly voice their preference for towels, a DMU minimises its own risks by continuing to order towels. Changing user preferences on environmental grounds will not always be easy, unless a green product is clearly less expensive.

A DMU may also perceive the principles of a green procurement programme as an encroachment on their purchasing authority, especially if their opinions are not taken into account. An example of this is a city bus depot, whose purchasing decision-makers were pushed by the managers of a green procurement programme to make certain changes toward greener products. The depot people did not react well to the imposition, and were not happy about being forced to choose products with which they were not familiar, while supposedly retaining all operative and budget responsibilities. Such resistance is enhanced by strong user preferences for existing products.

The running-in of new green products without the acceptance of—or, in some cases, with strong resistance from—most or all members of each DMU cannot be made and should not be attempted in public procurement. Users must have their say, because they can create operative problems if they do not like the product that has been chosen for them. A green procurement programme falters when the operators of copying machines refuse to run the machines with recycled paper. Buyers can slow down the order-delivery process if they consider that their expertise has not been heard. Managers responsible for budgets cannot be bypassed, especially if the green products will cost more than the least-cost alternative. Technical specialists, such as healthcare authorities or managers of public archives, have their own product requirements. Lack of consideration may put any of these parties into a defensive or hostile position, which may totally scupper the implementation of green purchasing for extended periods of time.

Organisational inertia will delay implementation, as will the existence of long procurement cycles. Acceptance by the DMU does not imply that a green product will be bought immediately. Many products are purchased with long-term contracts, which are changed periodically when products and suppliers are under review. Further delays can be expected when a selection of a particular product or an operating system in the past has locked in future choices for long time-periods. A clinical laboratory reagent system based totally on throw-away consumables is not environmentally friendly, but cannot be easily changed, because it is part of a much larger system which involves operating practices across the hospital and the processing of patient information.

The Organisation of the Procurement Function

The magnitude of the management task in the implementation of a green procurement programme depends largely on how the public purchasing function is organised. If the organisation has only a few decision-making units, a green procurement programme is easy to communicate to the decision-makers, and product and brand recommendations and choices can be managed with relatively small amounts of resources.

Some governments and cities have centralised all of their purchasing to a government supply organisation, which makes the product choices for all public organisations and is the sole source from which they can order goods. In some countries, government supply houses are organised geographically or functionally so that schools, hospitals, universities, postal services, etc. each have their own centralised supply. A supply house may stock the goods, or may have the suppliers make direct deliveries.

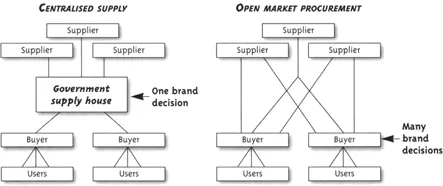

In centralised procurement, the decision about which brands will be available is made by the decision-making units of a governmental supply organisation (see Fig. 1). Each DMU is made up of experts from the supply organisation and from other government organisations, possibly augmented with users’ representatives. The DMU selects the brands that will be available from the supply for a given time-period, and reviews this decision before the end of the period.

The communication of a green procurement programme to the relatively few DMUs in a centralised procurement system is straightforward. The aims of the programme, product recommendations and other information can be communicated directly to the DMUs and the managers of the supply house. The choice of an environmentally preferable brand by the DMU changes all purchasing by all governmental units, because all must order through the central supply. In this system, green procurement programmes can be implemented, managed and controlled by a few individuals who participate in the work of the DMUs.

The switch to environmentally preferable products in this system is also slowed down by procurement inertia and users’ habits. The members of the centralised DMUs may hesitate in changing products and brands because they are open to criticisms from very many directions inside government organisations and from suppliers and distributors. Any objective or subjective failure of a new product may damage the position and the reputation of the employees of the government supply house. The adoption of multi-lining, i.e. the introduction of environmentally preferable products as one choice among the available product lines reduces this risk.

Centralised government procurement is becoming rare because many governments have decided to purchase on the open market. For example, Finland, the Netherlands and the United States have made this change in the last few years.1 All purchasing tasks in an open procurement organisation are delegated to cost centres, i.e. to operative units in central or local government. These have their own budgets and are responsible for their costs. The cost centres are free to make their product and brand choices within the limits of their own budgets without interference from above. Each cost centre has its own decision-making units, which select products and make contracts with suppliers and distributors as they see best.

Figure 1: Centralised Supply and Open-Market Procurement

The number of decision-making units in open-market procurement can be very large. There will be tens of thousands of individuals who make product and brand decisions in smaller countries, and millions in large ones, all of whom have their own product and brand preferences and attitudes toward environmental procurement. This organisational format makes the task of implementing environmentally preferable procurement (EPP) programmes similar to convincing all consumers to use environmentally better products. Extensive resources and long time-periods are required in implementing a programme, and emphasis will be shifted toward communication and education of the buyers to increase their motivation for using green products. The implementation of a green procurement programme is hampered by the lack of direct communication to the buyers, who are not readily identified (e.g. ‘Who buys copying paper in this office?’). In addition, the cost centres’ budget independence limits the role of a centralised green procurement programme in making recommendations about product and brand choices.

Many governments have combined open-market purchasing with a frame agreement system, in which a central procurement organisation negotiates discounts with suppliers, and acts as an adviser to the buyers about available products, brands and prices. The logic of these arrangements is that the size of the total volume that is purchased by the public organisations as a whole will facilitate a strong negotiation position and thus lower prices. The central organisation studies available products and suppliers, prices and delivery conditions, technical merits of products in different applications, and selects the products and suppliers that it considers the best, negotiates a frame agreement with the suppliers that specifies prices or, more commonly, discounts, which are given to governmental buyers. It produces lists of products and suppliers and the agreed frame prices or discounts and delivers the lists to the buyers to use, typically at an interval of six to twelve months.

The buyers may opt to use the frame agreement in their purchasing, or may try to improve the terms of the frame by renegotiating with the specified suppliers, or may use other suppliers or products if they so wish. Interviews conducted in Finland and Norway indicate that the small-quantity users tend to adhere to the frame, because separate negotiations for them are not economically or organisationally productive, and their lack of purchasing volume prevents them from gaining terms better than they get with the frame. Larger buyers, who can use their own volume as a leverage, and buyers in remote or other special locations, are prone to making less use of the frame, and renegotiate directly with suppliers.

The existence of frame organisations offers a possibility for the managers of an EPP programme to make sure that green products and brands are at least offered and recommended to the buyers. The central frame organisation also provides a good communication channel, because it is in touch with most of the buyers through its activities. The regular flows of information from the frame organisation to the buyers and users about the newest frame agreement conditions may serve as a channel for environmental messages. It is worth noting that not all government organisations do make use of the frame agreements: some have their own DMUs, and not all consumption can be affected through the frames because the final choice is with the local buyers and users.

Some government supply houses have been privatised and have become, in essence, private distributors, which compete with other suppliers for the custom of organisations of central and local governments. These tend to concentrate on governmental buyers, and some have retained large market shares in this segment.

Government-owned distributors operate on the principles of open markets and have several distribution methods. Some may work extensively with their own frame agreements, which they negotiate directly with manufacturers and other local distributors, normally without any formal governmental decision-making unit. Under these agreements, small-volume buyers can use the credit cards or credit lines issued by the distributor to make their purchases at the specified retailers or other supply houses at current frame prices or discounts. Larger buyers can specify their product preferences to some extent, and order goods in bulk from the distributors’ warehouses. Largest users decide their product choices and negotiate their prices and terms periodically, taking deliveries either from the warehouses of the distributors or as drop-shipments directly from the manufacturers.

The distributors offer a communication channel through which a section of governmental buyers can be reached. They know their customers, and often have regular mailings or campaigns, which can be used as channels of information concerning green procurement news. The decision-making power of a government-owned distributor concerning product choices is reduced almost to that of a normal wholesaler or office supply house, who will mostly concentrate on goods that are the easiest to sell and offer the best margins. The distributor is in competition with other suppliers, and will offer its customers the products they prefer. It can be persuaded to make available products from green lists, but the distributor is not always capable or willing to influence excessively the customers’ product decisions. The commercial interest of the firm is to attract the customer’s business via a certain product, not to increase costs by educating the customer on which product to choose.

Managers of green procurement programmes have little sway over the free-market distributors. They can wish for and, in the case of a government-owned distributor, can point out to the existence of a new procurement programme, but the decision of what products are offered and how they are promoted is in the hands of the distributors. Permanent changes in procurement patterns can be accomplished only through educating public buyers and users to demand green products from their suppliers.

The basic organisational structures described above relate to government units. Procurement programmes may also embrace non-governmental purchasing, when the government requires that its outside suppliers, or organisations otherwise financed by the government, must comply with set procurement rules. For example, the Finnish Law on Public Procurement 1505/92 (Laki julkisista hankinnoista, §6) specifies that the law also applies to purchases made by private firms, but which receive more than 50% of their financing from the government. A government may also require, like the US Environmental Protection Agency, that important suppliers follow the procurement rules set by the government unit. However, the running-in and control of non-governmental purchases by outside organisations may not be easy to accomplish, because of the lack of information and monitoring facilities.