![]()

1

Improving the public’s health through playful Endeavors

Julia Whitaker and Alison Tonkin

Introduction

Health is widely regarded as one of the most precious values in life, and the pursuit of health is a highly valued endeavor in both personal and public domains. Most developed regions, including the US, Canada, Western and Central Europe, as well as Nordic countries, rate health (along with life satisfaction) as what matters most to them in life (New Point de View 2015). A healthy life has become synonymous with life itself since, without some degree of healthy functionality, the living whole ceases to exist (Watt 2015). The relationship between a society’s economic, social, and political stability and the health of its citizens is widely recognized as a main determinant of its success (Stoever and Kim 2007).

In 2014, the National Health Service in the UK published a ‘Five Year Forward Review’ which highlights the central role of public health in achieving societal goals, by engaging people and communities as active players in the search for new ways of addressing health concerns (NHS England 2014). Health has become a ‘social movement’, marking a shift from formal to informal approaches to health improvement in ‘a persevering people-powered effort’ (del Castillo et al. 2016: 9) to find creative solutions to current health challenges.

A parallel social movement has arisen from the study of play and playfulness (Shephard 2013). Playfulness is widely recognized as an innate human trait crucial for interpreting the world and responsible for engendering the creativity of thought and behavior which allows for adaptation to its constantly changing circumstances (de Koven 2017). While playfulness is widely encouraged in childhood, with designated space, time and encouragement for play, permission for adults to play tends to be limited to specific circumstances and is usually associated with purposeful activity (Rogerson et al. 2013). However, the fact that humans have developed a wide range of spontaneous play behaviors ‘from doodling when bored to risky adventure play’ (Graham and Burghardt 2010: 403) suggests a significant function of playfulness in adulthood. A popular explanation for the continuation of play through the lifespan is that it supports the development of complex cognition and behavioral flexibility. Research into adult play acknowledges playfulness to be a variable which ‘enables people to transform a situation or an environment in a way to allow for enjoyment or entertainment’ (Proyer 2012: 1).

It is the transformational power of play and playfulness which now invites its serious consideration in the exploration of innovative approaches to the public health challenges of the 21st century. Recognizing the potential role of playfulness in relation to health demands a cultural shift from a ‘top down’ approach to one in which citizens can explore a new kind of creative freedom (Shephard 2013). Hannah asserts that the process of change ‘starts by planting seeds of the new culture in the soil of the old’ (Hannah 2014: 132): the playful pursuit of public health represents an attempt to add seeds of enjoyment and fun to the diverse mix of transformational possibilities.

Defining public health

Public health is a concept which represents society’s efforts to ‘improve the health of the population and prevent illness’ (Nuffield Council on Bioethics 2007: v). The emphasis on society means that, unlike medicine which focuses on the diagnosis, treatment and promotion of the health of an individual, public health requires society as a whole to embrace and engage, at local, national and international levels, with resources intended to provide the necessary conditions to live a healthy life (Chavan 2016).

With a rich and varied history, the concept of public health stretches back over ten thousand years to a time when nomadic lifestyles were replaced by a more communal and settled style of living (Science Museum n.d.). Societal change brought with it new challenges as contact between people, animals, and their associated waste products increased. Polluted water and the absence of appropriate waste disposal systems were responsible for the spread of disease and there was a growing recognition that this could be addressed through simple adaptations to this new way of life. Although there was little understanding of what contributed to the promotion of good health or the causes of disease, ‘health’ became a concept of communal concern leading to the emergence of a public approach to the health of the population (Science Museum n.d.).

The first recognized definition of public health practice was composed by Winslow in 1920. Nearly 70 years later, this was abbreviated and subsequently adopted by the World Health Organization (WHO), who define public health as ‘The science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life and promoting health through the organized efforts of society’ (Acheson, cited in WHO Regional Office for Europe 2017).

This definition reflects the importance of a dual approach to public health that relies on science to provide the surveillance, evidence base, and research capability to help people stay healthy and prevent ill health (Public Health England 2017) combined with the ‘art of public persuasion’ (Canadian Medical Association Journal 2000) which is needed to engage the public as active partners, enabling them to play their part in securing their own health and wellbeing wherever possible.

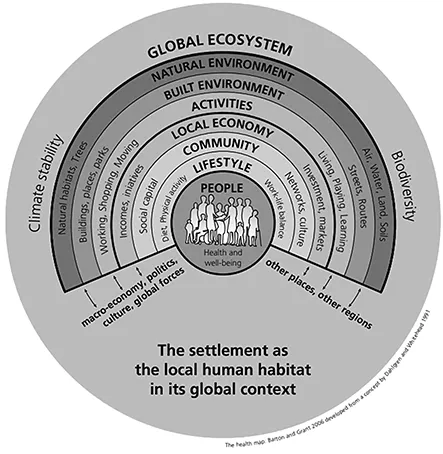

Modern public health practice necessitates partnership-working between everyone who contributes to the health of the population, acknowledging the multifaceted nature of health (Faculty of Public Health 2010). Many of the determinants of health and wellbeing that influence this are captured by Barton (2017) in Figure 1.1 which specifically recognizes the important contribution made by play. It also clearly identifies that policy and the role of the state are fundamental influences on public health, shaping the social circumstances of our lives, the communities we live in, and ultimately the choices we make when addressing risk factors to our health and wellbeing (Public Health England 2016).

FIGURE 1.1 The Settlement Health Model.

Source: Barton (2017); reproduced by kind permission of Professor Hugh Barton, University of the West of England

The significance of play is also acknowledged by the American Public Health Association (2017), who state that ‘Public health promotes and protects the health of people and the communities where they live, learn, work and play’. Within this definition, play is identified as a unitary aspect of the life of the community, making play a worthy concept to explore in the context of pursuing public health. Play takes many forms (Sutton-Smith 1980) and it is ‘the richness and variety of our human games which make for a healthy and vibrant culture’ (Kane 2004:7). A synthesis of the insights about the nature and function of play, provided by both the natural and the social sciences, opens-up the debate about the place of play in contemporary society (Kane 2004).

Nevertheless, play as a unitary concept is contentious: Gauntlett et al. (2010: 46) note that ‘the world is still far from sharing a single view on the role or value of play in society’. Advocating play as a means of facilitating public health may be antagonistic but this does not preclude exploration of its status as a potentially low cost, high impact, and enjoyable means of engaging and enabling society’s contribution to the public health agenda.

Defining play

Definitions of play embedded in both the academic literature and in common parlance have provocatively incorporated elements of both the empirical and the philosophical, the rational and the esoteric. Play is explained as an innate drive, essential to mammalian survival and development (Koch 2017), yet widely recognized to be a voluntary activity (Garvey 1990) which is freely chosen (Hughes 2012) and culturally determined (Gosso and Almeida Carvalho 2013). The paradox of play (McCarthy 2007) revolves on the apparent contradiction that play is deemed essential to healthy growth and development (Ginsberg 2007) while simultaneously representing an exercise of personal free will (Baggini 2015).

In his classic text Homo Ludens, Huizinga (1949) identifies ‘free choice’ as the first main characteristic of play, differentiating it from all other aspects of natural or cultural life. Play is, perhaps, our only ‘optional’ pursuit, having neither specified purpose nor pre-determined ending (Gadamer 2013[1960]). The free nature of play is complemented by its identification with something out-of-the-ordinary, detached from everyday life yet integral to it; ‘a necessity both for the individual … and for society by reason of the meaning it contains, its significance, its expressive value, its spiritual and social associations’ (Huizinga 1949: 9). Play transfers and transforms the meanings attributed to the mundane and, in so doing, has the power to create the world anew (McCarthy 2007).

Contemporary research endorses ‘freedom to play’ as essential to the development of positive health and wellbeing, as well as to social and ecological survival (Gray 2009). Play is known to have a significant role in physiological development (Trawick-Smith 2014); in the maturation of social and communication skills (Goldstein 2012); and in creativity and problem solving (Brown 2008). There is also robust support for its role in the development of the flexible and non-specialist behaviors necessary for survival in a constantly changing ecological and cultural context (Pellegrini, 2009). The flexibility of movement, thought and behavior that are characteristic of play correspond to an adaptability to change that is essential for the evolution of strong and healthy communities (Sutton-Smith 1997).

Free to play

The notion of freedom is encapsulated in the language used to describe play throughout history and across cultures. Freedom of movement is the concrete starting point for many play words (Huizinga 1949), whether referring to the movement of the wind and waves (the Sanskrit krīdati); the frolicking of young children and animals (the Greek paidia); or lively self-expression through dance and drama (the High German leich, the Anglo-Saxon lâcan). Yet the freedom integral to the concept of play goes beyond its allusion to freedom of physical movement: it also infers freedom of thought, behavior and opinion (the Latin ludere, meaning to twist words; the Chinese wan, referring to jesting or mockery). Perhaps most relevant to our consideration of play as it relates to the health of the social group, is the Indo-European root of the Old-English word plegian (also common to Celtic, German, Slavic and possibly Latin), namely the word dlegh meaning ‘to engage oneself’ (Kane 2004). Play is essentially a social activity (McLean and Hurd 2014), a means of ‘engaging oneself’ with the external world, with others, and with different parts of the self. It is the complex interplay between social engagement and the health of individuals and communities (Bennett 2005) which reinforces the role for play in the public health debate.

All social activities come about in relation to cultural narratives and their embedded practices, and the notion of engaging, or indulging oneself, with the freedom of movement, thought and behavior that is play has influenced the popular perception of play throughout history.

The historical evolution of play as a means of social engagement

The nature of play has preoccupied scholars since the time of the ancient Greeks. Plato wrote in The Republic (c.360 BCE: Waterfield 1993) of the importance of freedom, for learning and for understanding the human condition (Frost et al. 2012). Elements of play were intrinsic to a range of cultural activities in Ancient Greece (500–323 BCE): the playing of games and music featured in both ceremonial and social gatherings, and drinking parties included the exchange of verses and riddles. In the agra...