eBook - ePub

Metafiction

About this book

Metafiction is one of the most distinctive features of postwar fiction, appearing in the work of novelists as varied as Eco, Borges, Martin Amis and Julian Barnes. It comprises two elements: firstly cause, the increasing interpenetration of professional literary criticism and the practice of writing; and secondly effect: an emphasis on the playing with styles and forms, resulting from an enhanced self-consciousness and awareness of the elusiveness of meaning and the limitations of the realist form.

Dr Currie's volume examines first the two components of metafiction, with practical illustrations from the work of such writers as Derrida and Foucault. A final section then provides the view of metafiction as seen by metafictional writers themselves.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Defining Metafiction

1 Metafiction*

Robert Scholes is one of several writers who sought to give definition to William Gass's term ‘metafiction’ in the early 1970s. This article attempts to link that term to ideas which derive from John Barth's essay The Literature of Exhaustion’ (see Part Three) to describe the attempts of experimental fictions of the 1960s to ‘climb beyond Beckett and Borges’ (the principal subjects of Barth's essay) towards ‘things that no critic can discern’. These undiscernible things are best thought of as moments of critical vertigo in which the relations between real life and representation are no longer clear, either within or beyond the fiction.

In a volume dedicated to the idea that metafiction is a border-line territory between fiction and criticism, this essay has a special place. Its argument begins with the idea that there are four aspects of fiction (fiction of forms, ideas, existence and essence) which correspond to four critical perspectives on fiction (formal, structural, behavioural, and philosophical) in the sense that each critical perspective is the most appropriate response to the four aspects of fiction. The argument then moves on to claim that, because metafiction ‘assimilates all the perspectives of criticism into the fictional process itself, this scheme offers a model for the typology of metafictions, so that four distinct directions in metafiction can be understood to pertain to these four aspects of both fiction and criticism. Like most typologies, Scholes's relies on relational rather than absolute categories, and difficulties of determining the dominant aspect of any given metafiction can present real problems to the critic. The interest of the essay lies mainly in the idea that when a novel assimilates critical perspective it acquires the power not only to act as commentary on other fictions, but also to incorporate insights normally formulated externally in critical discourse. Scholes seems to conclude that the critic, and even the ‘metacritic’, is redundant with regard to such insights, but only, I think, because he is writing in the immediate prehistory to the golden age of the American metacritic, an age in which criticism sought to incorporate the same kind of aporetic insight into subject and object relations.

This essay was originally published in The Iowa Review in conjunction with Robert Coover's short story ‘The Reunion’.

Many of the so-called anti-novels are really metafictions.

(W.H. Gass)

And it is above all to the need for new modes of perception and fictional forms able to contain them that I, barber's basin on my head, address these stories.

(Robert Coover)

the sentence itself is a man-made object, not the one we wanted of course, but still a construction of man, a structure to be treasured for its weakness, as opposed to the strength of stones

(Donald Barthelme)

We tend to think of experiments as cold exercises in technique. My feeling about technique in art is that it has about the same value as technique in lovemaking. That is to say, heartfelt ineptitude has its appeal and so does heartless skill; but what you want is passionate virtuosity.

(John Barth)

I

To approach the nature of contemporary experimental fiction, to understand why it is experimental and how it is experimental, we must first adopt an appropriate view of the whole order of fiction and its relation to the conditions of being in which we find ourselves. Thus I must begin this consideration of specific works by the four writers quoted above with what may seem an over-elaborate discussion of fictional theory, and I ask the reader interested mainly in specifics to bear with me. In this discussion I will be trying not so much to present a new and startling view of fiction as to organize a group of assumptions which seem to inform much modern fiction and much of the fiction of the past as well. Once organized, these assumptions should make it possible to ‘place’ certain fictional and critical activities so as to understand better both their capabilities and limitations.

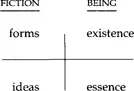

One assumption I must make is that both the conditions of being and the order of fiction partake of a duality which distinguishes existence from essence. My notion of fiction is incomplete without a concept of essential values, and so is my notion of life. Like many modern novelists, in fact like most poets and artists in Western culture, ancient and modern, I am a Platonist. One other assumption necessary to the view I am going to present is that the order of fiction is in some way a reflection of the conditions of being which make man what he is. And if this be Aristotelianism, I intend to make the most of it. These conditions of being, both existential and essential, are reflected in all human activity, especially in the human use of language for esthetic ends, as in the making of fictions. Imagine, then, the conditions of being, divided into existence and essence, along with the order of fiction, similarly divided. This simple scheme can be displayed in a simple diagram, [see Fig. 1.1].

fig. 1.1

The forms of fiction and the behavioral patterns of human existence both exist in time, above the horizontal line in the diagram. All human actions take place in time, in existence, yet these actions are tied to the essential nature of man, which is unchanging or changing so slowly as to make no difference to men caught up in time. Forms of behavior change, man does not, without becoming more or less than man, angel or ape, superman or beast. Forms of fiction change too, but the ideas of fiction are an aspect of the essence of man, and will not change until the conditions of being a man change. The ideas of fiction are those essential qualities which define and characterize it. They are aspects of the essence of being human. To the extent that fiction fills a human need in all cultures, at all times, it is governed by these ideas. But the ideas themselves, like the causes of events in nature, always retreat beyond the range of our analytical instruments.

Both the forms of existence and the forms of fiction are most satisfying when they are in harmony with their essential qualities. But because these forms exist in time they cannot persist unchanged without losing their harmonious relationship to the essence of being and the ideas of fiction. In the world of existence we see how social and political modes of behavior lose their vitality in time as they persist to a point where instead of connecting man to the roots of his being they cut him off from this deep reality. All revolutionary crises, including the present one, can be seen as caused by the profound malaise that attacks men when the forms of human behavior lose touch with the essence of human nature. It is similar with fiction. Forms atrophy and lose touch with the vital ideas of fiction. Originality in fiction, rightly understood, is the successful attempt to find new forms that are capable of tapping once again the sources of fictional vitality. Because, as John Barth has observed, both time and history ‘apparently’ are real, it is only by being original that we can establish a harmonious relationship with the origins of our being.

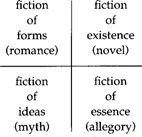

Now every individual work of fiction takes its place in the whole body of fictional forms designated by the upper left-hand quadrant in Fig. 1.1. Among all these works we can trace the various diachronic relationships of literary genres as they evolve in time, and the synchronic relations of literary modes as they exist across time. As a way of reducing all these relationships to manageable order, I propose that we see the various emphases that fiction allows as reflections of the two aspects of fiction and the two aspects of being already described. Diagrammatically this could be represented by subdividing the whole body of fictional forms (the upper left-hand quadrant of Fig. 1.1) into four subquadrants, in [the manner shown in Fig. 1.2].

fig. 1.2

Most significant works of fiction attend to all four of these dimensions of fictional form, though they may select an emphasis among them. But for convenience and clarity I will begin this discussion by speaking as if individual works existed to define each of these four fictional categories.

The fiction of ideas needs to be discussed first because the terminology is misleading on this point. By fiction of ideas in this system is meant not the ‘novel of ideas’ or some such thing, but that fiction which is most directly animated by the essential ideas of fiction. The fiction of ideas is mythic fiction as we find it in folk tales, where fiction springs most directly from human needs and desires. In mythic fiction the ideas of fiction are most obviously in control, are closest to the surface, where, among other things they can be studied by the analytical instruments of self-conscious ages that can no longer produce myths precisely because of the increase in consciousness that has come with time. Existing in time, the history of fiction shows a continual movement away from the pure expression of fictional ideas. Which brings us to the next dimension, the fiction of forms.

The fiction of forms is fiction that imitates other fiction. After the first myth, all fiction became imitative in this sense and remains so. The history of the form he works in lies between every writer and the pure ideas of fiction. It is his legacy, his opportunity and his problem. The fiction of forms at one level simply accepts the legacy and repeats the forms bequeathed it, satisfying an audience that wants this familiarity. But the movement of time carries such derivative forms farther and farther from the ideas of fiction until they atrophy and decay. At another level the fiction of forms is aware of the problem of imitating the forms of the past and seeks to deal with it by elaboration, by developing and extending the implications of the form. This process in time follows an inexorable curve to the point where elaboration reaches its most efficient extension, where it reaches the limits of tolerable complexity. Sometimes a form like Euphuistic fiction or the Romances of the Scudery family may carry a particular audience beyond what later eras will find to be a tolerable complexity. Some of our most cherished modern works may share this fate. The fiction of forms is usually labelled ‘romance’ in English criticism, quite properly, for the distinguishing characteristic of romance is that it concentrates on the elaboration of previous fictions. There is also a dimension of the fiction of forms which is aware of the problem of literary legacy and chooses the opposite response to elaboration. This is the surgical response of parody. But parody exists in a parasitic relationship to romance. It feeds off the organism it attacks and precipitates their mutual destruction. From this decay new growth may spring. But all of the forms of fiction, existing in time, are bound to decay, leaving behind the noble ruins of certain great individual works to excite the admiration and envy of the future – to the extent that the future can climb backwards down the ladder of history and understand the past.

The fiction of existence seeks to imitate not the forms of fiction but the forms of human behavior. It is mimetic in the sense that Erich Auerbach has given to the term ‘mimesis’. It seeks to ‘represent reality’. But ‘reality’ for the fiction of existence is a behavioristically observable reality. This behavioral fiction is a report on manners, customs, institutions, habits. It differs from history only, as Henry Fielding (and Aristotle) insisted, in that its truth is general and typical rather than factual and unique. The most typical form of behavioral fiction is the realistic novel (and henceforth in this discussion the term ‘novel’ will imply a behavioristic realism). The novel is doubly involved in time: as fiction in the evolution of fictional forms, and as a report on changing patterns of behavior. In a sense, the continual development of its material offers it a solution to the problem of formal change. If it succeeds in capturing changes in behavior it will have succeeded in changing its form: discovery will have created its appropriate technique. But as Mark Schorer has persuasively argued, it may be rather that new techniques in fiction enable new discoveries about human behavior to be made. So the great formal problem remains, even for behavioristic fiction. A further probl...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Longman Critical Readers

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- General Editor's Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part One: Defining Metafiction

- Part Two: Historiographic Met Afiction

- Part Three: The Writer/Critic

- Part Four: Readings Of Metafiction

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Metafiction by Mark Currie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.