![]()

1

Guiding Principles for School Mathematics

FOCAL POINTS

• Beginnings

• Curriculum

• Planning

• Assessment

• Technology

• Manipulatives

BEGINNINGS

How wonderful it would be if we knew everything about kids, teaching, mathematics, and the teaching of mathematics. We could bottle it, sell It, become rich, and solve a lot of problems for everyone in the process. We all know there is no magic formula for teaching mathematics. Each of us struggles to find ways to reach students at levels appropriate for them. In the process of attempting to find keys, we often stumble and miss objectives, but we also learn a variety of things that can be catalogued and used at a later date in other settings. (Brumbaugh et al., 1997, p. 86)

As you continue your education and teaching career, you should compile a list of resources that helps your students develop the necessary skills to learn mathematics.

You, as a prospective teacher, should be aware of age level, developmental characteristics, and interaction dynamics of students. Each student needs to be understood as an individual. You also need to know mathematics. You should want to understand the foundations of the material you are teaching so you can provide explanations that make sense.

In addition to knowing mathematics, you need to know about teaching mathematics. Teaching a modern mathematics curriculum demands that you go beyond the statement, “Because I said so and I am the teacher.” You have to know what sequence of presentation is most appropriate for your students (which might be different from that in your text or list of objectives for the year). What manipulative should be used in what capacity becomes a critical consideration as topics are introduced for the first time. How do you know when to move from the concrete stage? Another question to answer! We need to start.

Students’ Opinions About Mathematics

Look at what kids say when responding to “Why Do We Study Math in School?”

“Because it’s hard and we have to learn hard things at school. We learn easy stuff at home like manners.” Corrine, grade K

“Because it always comes after reading.” Roger, grade 1

“Because all the calculators might run out of batteries or something.” Thomas, grade 1

“Because it’s important. It’s a law from President Clinton and it says so in the Bible on the first page.” Jolene, grade 2

“Because you can drown if you don’t.” Amy Beth, grade K

“Because what would you do with your check from work when you grow up? Brad, grade 1

“Because you have to count if you want to be an astronaut. Like 10 … 9 … 8 … 7… blast off!” Michael, grade 1

“Because you could never find the right page.” MaryAnn, grade 1

“Because when you grow up you couldn’t tell if you are rich or not.” Raji, grade 2

“Because my teacher could get sued if we don’t. That’s what she said. Any subject we don’t know—Wham! She gets sued. And she’s already poor.” Corly, grade 3 (from a presentation in Philadelphia by Joseph Tate)

Prior to entering elementary school, children have a multitude of exposures to mathematics and are generally anxious to learn more about the subject. By the time they leave fifth grade, many of them are not nearly as excited about learning mathematics. Why? There are many factors, some of which are easy to identify and some of which are next to impossible to spot. Society plays an important role in students’ perceptions of mathematics. If an adult says, “I don’t like math,’’ it is likely that others in the conversation will support the statement by saying, “Me, too.” Students hear statements like that and soon conclude that mathematics is not a popular thing to know. Then they hear people say things like, “I never need math,” and the value of the subject goes down another notch. That context provides a wonderful opportunity to share The Math Curse (Scieszka, 1995) with your class. This book is a satire on different types of mathematics problems that have been posed to students. In the process, you will be integrating mathematics and literature and the class will learn about a student who realizes that mathematics is everywhere and, in the process, learns how to deal with it.

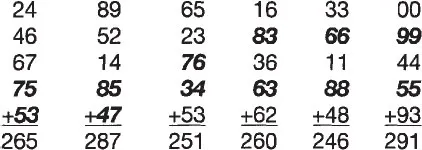

Society is not the only culprit in this discussion, however. Teachers, curriculum, tests, textbooks, and a number of other factors contribute to the negative attitudes that students develop about mathematics. You cannot dictate or control how your colleagues teach, but if you provide a dynamic, inviting mathematics class, they will hear about it from your students. You may be able to influence attitudes by being a member of a school mathematics committee and sharing ideas learned from conferences and workshops. Suppose, for example, the objective for your class is to add several two-digit numbers where regrouping is involved. You could assign several problems or you could present the following situation to them. (T represents a teacher comment and S shows a student comment.)

TRICK

T: | “We are going to add five 2-digit numbers. You will pick two of them and I will pick three of them. When we are done, the sum will be 247. For now, do not repeat the digits within an addend.” |

Write 247 in “standard column addition format” so the students can see it.

T: | “Pick a 2-digit number.” |

S: | “35” (Write it above the ones and tens digits of the sum.) |

T: | “What is your second addend?” |

S: | “78” (Write it in the respective columns above the 35.) |

T: | “I pick 49, 21, and 64 (in any order).” (Write them in the respective columns above the 78.) |

In almost all settings, the students will now add to see if you got the answer right. Generally, they want to know if you can do that all the time or how it works. Either way, they are asking you to do another problem and, in the process, they will practice more addition.

Another example that involves both addition and subtraction is “1,089.” When this is done with a class, each student would do a different example. The numbers shown here are for explanation and clarification.

TRICK (1089)

T: | “Write any 3-digit number.” “Do not repeat the digits.” (479) |

T: | “If I reverse the digits in my number, what do I get?” |

S: | “974.” |

T: | “Which is larger, 479 or 974?” |

S: | “974.” |

T: | “Subtract the smaller from the larger. If your subtraction answer is 99, write it as 099.” (974 – 479 = 495) |

T: | ‘Take that answer and reverse its digits, adding it to its reversal. (495 + 594 = 1089) |

S: | “We all get the same answer!” |

S: | “Will that always work?” |

T: | ‘Try another one and see.” |

Here again the students are asking to do another problem. These problems are so intriguing for students that they eagerly strive to discover the “secret” and then tell others about it.

You often have limited control over the composition of your class, the basic objectives for the year, the textbook, and a multitude of other factors. These items are not necessarily barriers, but they can be challenges. You are the local professional in your classroom. It is your responsibility to devise ways to overcome resistances that occur as you go about providing your students with the best possible mathematics education.

Lynn Oberlin provides a list entitled “How to Teach Children to Hate Mathematics.”

Children generally do not hate mathematics when they start school. This is a trait which they acquire as a part of their elementary school training. The feat of loathing mathematics can generally be accomplished if the teacher will use one or more of the following procedures.

1. Assign the same work to everyone in the class. This technique is effective with about two thirds of the class. The bottom third of the class will become frustrated from trying to do the impossible while the top third will hate the boredom. WARNING: This MAY NOT be effective with about the middle

of the students.

2. Go through the book, problem by problem, page by page. In time, the drudgery and monotony is bound to get to them.

3. Assign written work every day. Before long, just the word “mathematics” will remove every smile in the room.

4. Be sure that each student has plenty of homework. This is especially important over the weekends and vacation periods.

5. Never correlate mathematics with life situations. A student might find it useful and get to enjoy mathematics.

6. Insist there is ONLY one correct way to solve each problem. This is very important as some creative student might look for different ways to solve a problem. He could even grow to like math.

7. Assign mathematics as a punishment for misbehavior. The association works wonders. Soon math and punishment will take on the same meaning.

8. Be sure that ALL students complete ALL the review work in front of the textbook. This ought to last until Thanksgiving or Christmas, and is certain to kill off the interest of most students.

9. Use long drill type assignments with many examples of the same type problem, (for example: 30 long column addition problems) This type of assignment requires little teacher time and keeps the students occupied for a long time. The majority of the pupils are sure to dislike it.

10. Always insist that papers are prepared in a certain way. Name, date, page number, etc., must each be placed in a specific spot. If a student fails to follow this procedure, tear up his paper and let him start over again. Instant humiliation and despair are almost guaranteed.

11. Lastly, insist that EVERY problem worked incorrectly be reworked until it is correct. This procedure is most effective in promoting distaste for math and if followed very carefully, the student may even learn to detest his teacher as well. (Oberlin, 1985)

What we do, how we do it, what we say, and how we say it all influence how children learn mathematics. It is your responsibility to ensure that in your classroom each child develops a positive attitude about mathematics and its role in their lives. If we are lucky, this spills over into the home.

Exercises

1. Do each of the problems listed here (the left one first, the one to its right second, etc.). The italicized, bold numbers are those supplied by the student. A new hint is given as you move to the right in the problems. What is the secret to doing the trick?

2. Explain how the trick in Exercise 1 of this section works.

3. Do a trick similar to the one in Exercise 1 of this section using seven 4-digit addends. Describe the general answer and explain your conclusions.

4. Find another number trick that involves addition. Do the trick with a class of elementary students who have the appropriate background. Describe the reaction of the students.

Things to Do When You Have Three Minutes of Extra Time

One of the quickest ways to encounter problems with a class is to ask them to be quiet until the end of the period. They will find something to do, honest. You are best advised to have something to occupy their minds in situations like this, and games and tricks are wonderful items to use.

You could use something like a reprint of a problem-solving problem (see http://www.olemiss.edu/mathed/brain/). This could either be shown directly from the Web, copied and made into a transparency, or distributed to each student.

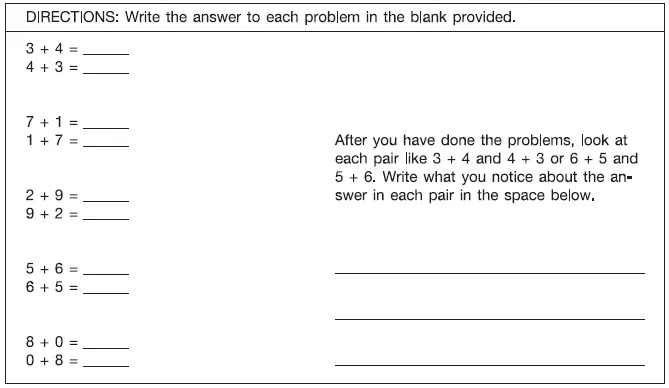

The problem-solving problems can be a part of your set of learning centers. You could color coordinate folders, with each color representing a different topic, concept, or operation. In each folder, place a game, trick, problem, or activity related to what you have covered during the year. During these few spare minutes, students could be directed to work in a folder of their choice, or you could assign a particular folder to a student or group. In a class that is working on addition facts and learning to use calculators, you could give a list of problem pairs like those in Table 1.1 and ask them to arrive at a conclusion.

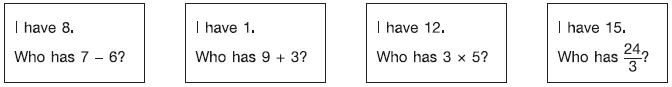

Games can be used to fill those extra few minutes. Doing something like the “I have-Who has?” game can provide needed drill while teaching the value of paying attention. In the I have-Who has? game, each card contains two pieces of information: a question and the answer to a problem on another card. The cards are distributed to all students. One individual reads their problem and all the other players work it. The individual holding the card with the right answer reads the “I have” statement and then asks the question below it. Each answer within the set is unique. Table 1.2 shows some sample cards. There are many other productive things that can be done in those few extra minutes.

TABLE 1.1

Exercises

5. Locate a Web site that lists problem-solving problems appropriate for elementary school students. Provide the name of the site, the address, and a brief description of the site.

6. Present an appropriate problem-solving problem you found on a Web site to a group of elementary students and describe their reactions.

7. Locate a Web site that lists games, tricks, activities, or technology appropriate for elementary school students. Provide the name of the site, the address, and a brief description of the site.

8. Present an appropriate game or trick you found on a Web site to a group of elementary students and describe their reactions.

TABLE 1.2

What to Do With th...