![]()

The Present

Metropolis collage, by the author.

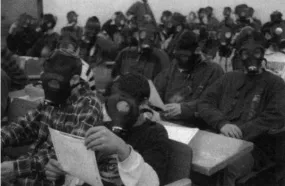

Only a test: Israeli students wear gas masks to class Wednessday during a nationwide security drill during which mock chemical warfare conditions were conducted in civilian situations.

Exhumation detail: A Serb steals the casket of an exhumed body from a Serb-held cemetery Wednessday in Ilidza near Sarajevo. Many Serbs are digging up relatives in preparation for fleeing the area.

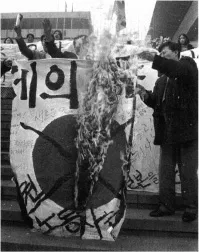

A day in the life of postmodern war. Four pictures from the January 25, 1996, Oregonian, page A2. Mideast, Balkans, Asia, Central America. As the twentieth century comes to an end various conflicts fester and rage on every inhabited continent. They may range from domestic terrorism to conventional war but all carry the potential of apocalypse, thanks to the creation and proliferation of biological, chemical, and nuclear technologies and weapons. Paradoxically enough, all of these conflicts seem poised on the edge of peace. Postmodern war’s incredible instability is both a tremendous danger and a utopian possibility. Photos: AP Wide World Press.

Peaceful stroll: An Indian girl walks past a Mayan cross and a miltary police officer outside Mexican–Zapatista peace talks in San Andres Larranzar. Rebel leaders said Wednesday that they would sign an agreement expanding the rights of Indians clearing the way for a peace accord in Chiapas state.

Upset over islet: Protesters burn a Japanese flag Wednesday near the Japanese Embassy to dispute Japan’s claim that it owns tiny Tok-do, an island halfway between South Korea and Japan.

The normalization of unspeakable horror. A Christmas Card from the Minuteman Service News, the journal for the ICBM crews of the U.S. Air Force. While many nuclear warheads and ICBMs have been dismantled, enough remain to destroy the world as we know it. So many Christmases have passed under this sword of apocalypse that few now fear it. That is not a rational reaction, but then making an ICBM the centerpiece of a Christmas card isn’t either. Yet it is a peculiar version of official rationality, in technology, science, and politics, that has justified, and therefore actualized, these weapons. Minuteman Service News, November–December 1974, no. 77, page 3.

The imperialistic hubris of official icons. The world is their oyster. While all official insignia from the Department of Defense do not inscribe the world as militarized U.S. territory it is remarkable just how many do. Here we see the badges for commandos (the Navy SEALs and the Joint Special Operations Command that unites all special forces), for space forces (Space Command), for researchers (the Strategic Computing Program and for DARPA as a whole) all feature the world as their backdrop. The other logos are corporate (GTE) and from corporate–military conferences in the Czech Republic and the United States. The message is clear in all of these symbols. War is global, militarization is global, our reach is global.

![]()

Real Cyberwar

Resistance to Pure War can only be based on the latest information.

—Paul Virilio and Sylvere Lotringer (1983, p. 136)1

Simulation and Genocide

During the Bosnian peace talks of 1995 the negotiators for the United States used state-of-the-art real-time simulation computer technoscience to bring a temporary halt to the genocide. At a key point in the Dayton Accord meetings U.S. officials took the Bosnian, Croatian, and Serbian presidents into the “Nintendo” room where they could see a real-time three-dimensional map of the disputed territories. Secretary of State Warren Christopher bragged that “We were able to, in effect, ‘fly’ the people over the area they were talking about, showing them the map on a large video screen so they could actually see what they were talking about.” This is why the negotiations were held at Wright–Patterson Air Force Base in the first place; it is where the term “bionics” was coined (Steele, 1995), where science fiction writers are invited to plan for future war (C. H. Gray, 1994), and where virtual reality and human–machine interface applications are developed. The French, Russians, and other Europeans excluded from this show were, diplomatically speaking, pissed off. Still, it worked, even though, as the French noted, the map did not include data on the ethnic origin of the population.2 The promise of total information, which for many today means total power, was enough to convince the warring presidents.

This incident was just one of literally millions of war-related events that happen every day. But its mixture of ancient hatreds with the newest of technology in the service of intimidation, maybe even peacemaking, at the behest of the world’s “only” superpower3 make it a good one to unpack. It reveals, among other things, how powerful, but limited, the forces pushing for peace and stability are. The international model of open war now equates war to a virulent disease, when it does not see it as a righteous cause, which it usually does. So while everyone calls for peace, every conceivable justification is mobilized for war, including God, blood, gold, honor, oil, water, history, and the need for peace itself. And many who make these justifications are even sincere, none more so then those who used the latest computer technology to attempt the inoculation of potential combatants against the seductions of more genocide in blood-soaked Bosnia.

The Bosnian conflict, in which satellites are used to find the mass graves of the recent victims of thousand-year-old hatreds, isn’t the only confusing conflict. Consider these:

• PSYOPs (psychological operations) U.S. troops battle voodoo imagery in Haiti.

• Russian troops attempt with little success to crush cell-phone-linked Moslem rebels in the Caucasus.

• Religious revolutionaries attack liberal regimes with assassination (Algeria, Egypt), bombs (United States, France), and gas (Japan), even in alliance with their hated enemies, as with the Orthodox Jewish and Hamas Moslem alliance in Israel against peace. On June 15, 1995, President Clinton orders the United States to prepare for bioterrorism (network TV reports, January 30, 1996).

• Zapatista insurrectionists shake Mexico using a combination of traditional and cyber-guerrilla tactics and strategies.

But this bricolage, this … mess, is not unexplainable. It is just that the explanation isn’t simple. Imagine war as Proteus, the Greek demigod who could change his form as long as he touched the ground. Hercules had to hold him up in the air during their wrestling match in order to defeat him. Well, protean war is wrestling with the present, trying to find a way to survive as a coherent creature (discourse, culture, or way of life, the label can vary) in the face of extraordinary changes in the technologies and politics of conflict.

War explodes around the planet, relentlessly seeking expression in the face of widespread moral, political, and even military censorship, since the old stories of ancient tribal grievances and of the supremacy of male courage, and therefore war, don’t sell everywhere. Peace even seems particularly popular and much effort, much military effort, goes into what is labeled peacemaking, but the situation remains chaotic. Continual technoscientific changes have led to the incredible spread of mass weapons (chemical, biological, nuclear [CBN]) to dozens of states, nationalities, and even grouplets, while the continual outbreaks of war are almost contained by the spread of worldwide high-speed communications, the integration of the world economy, and the proliferation of peace initiatives.

Just what is happening? It is the argument of this book that war is undergoing a crisis that will lead to a radical redefinition of war itself, and that this is part of the general worldwide crisis of postmodernity. While this crisis is far from resolved, the range of possible outcomes is becoming clear. In terms of war there would seem to be two main future options: a utopian redefinition of war’s function (simulation), or some sort of horrific, even apocalyptic, reductio ad absurdum of real war’s current logic (genocide).

To sort out the whys and the maybes of these possible futures a great and complicated story needs to be told—the story of postmodern war. It starts with a discussion of the label itself.

Why “Postmodern” War?

The mania of the last few hundred years for labeling new types of war has a sound basis. War seems to be changing more quickly then it ever has before, while it assumes unprecedented destructive power as well. Labels can be misleading, as I will show in the case of “cyberwar” below, but they are also important. I don’t choose mine lightly. Whether, for example, the Persian Gulf War is seen as a new form of war or as a continuation of older types is more than an academic issue.

“The Persian Gulf conflict,” intones Business Week, “will almost certainly come to mark the transition between two forms of war.” The magazine goes on to specify what it considers the most important elements of this “new war”: (1) “the integration of high-technology-based systems”; (2) “a huge array of computer and communications systems”; and (3) the realization that “politics and public relations play” a crucial role “in achieving military objectives” (Business Week Staff, 1991a, b, c, pp. 39, 42, 37).

But this is not new. It is not all that different from Vietnam. While the War for Kuwait certainly broke some new ground (and most violently), for the last half of this century it has been clear that war is changing fundamentally. The more insightful observers have noticed the implications of hightech weapons, especially computers, and the permanent military mobilization that has existed since 1945. They have called this new type of war many things, among them: permanent war (Melman, 1974), technology war (Possony and Pournelle, 1970), high-technology war or technological war (Edwards, 1986c), technowar or perfect war (Gibson, 1986), imaginary war (Kaldor, 1987), computer war (Van Creveld, 1989), war without end (Klare, 1972), Militarism USA (Donovan, 1970), light war (Virilio, 1990), cyberwar (Davies, 1987; Der Derian, 1991; Arquilla and Ronfeldt, 1993), high modern war (Der Derian, 1991), hypermodern war (Haraway, personal communication, 1991), hyperreal war (Bey, 1995), information war, netwar (Arquilla and Ronfeldt, 1993), neocortical warfare (Szafranski, 1995), Third Wave War (Toffler and Toffler, 1993); Sixth Generation War (Bowdish, 1995), Fourth Epoch War (Bunker, 1995), and pure war (Virilio and Lotringer, 1983).

Though all of these labels have something to recommend them, none do justice to the complexity and sweeping nature of war’s recent changes. For example, Virilio and Lotringer’s “pure war” does capture poetically the deep penetration of war into contemporary culture, certainly in the West, especially into politics.4 But in a strong sense the mass annihilation of civilians in World War II was pure war, the obliteration of Hamburg, Dresden, Tokyo, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki countering that of Warsaw, Rotterdam, and Coventry, not to speak of the earlier “Rape of Nanking” and the “Final Solution” of Treblinka, Auschwitz, Dachau, and the other death camps. War was total. What we have now is very “impure” war, called “imperfect” war by some, coming to the fore because pure total war has become, thanks to technoscience, suicidal. War is diffused throughout the culture, helping shift gender definitions, structuring the economy, selling products, electing presidents, and boosting ratings. But the actual battles are not decisive or heroic; they are confusing, distant, and squalid. More is happening to war than just high technology, or computers, or speed as light, or cybernetics, or the militarization of information.

I call it postmodern war.5 Why choose “postmodern” over the other possible labels? There seem to be two good reasons. First, modern war as a category is used by most military historians, who usually see it as starting in the 1500s and continuing into the middle or late twentieth century. It is clear that the logic and culture of modern war changed significantly during World War II. The new kind of war, while related to modern war, is different enough to deserve the appellation “postmodern.” Second, while postmodern is a very complex and contradictory term, and even though it is applied to various fields in wildly uneven ways temporally and intellectually, there is enough similarity between the different descriptions of postmodern phenomena specifically and postmodernity in general to persuade me that there is something systematic happening in areas as diverse as art, literature, economics, philosophy, and war.

This is particularly true of the importance of information to postmodernity. As a weapon, as a myth, as a metaphor, as a force multiplier, as an edge, as a trope, as a factor, and as an asset, information (and its handmaidens—computers to process it, multimedia to spread it, systems to represent it) has become the central sign of postmodernity. In war information (often called intelligence) has always been important. Now it is the single most significant military factor, but still hardly the only one.

We have been living in the era of postmodern war since 1945 and cold wars are an integral part of it. Edward Luttwak defines cold war as: “International conflict in which all means other than overt military force are used” (1971, p. 244). The United States versus USSR “Cold War” (capitalized) was the most famous of these, but it wasn’t unique. Calling cold war (lowercase) info- or cyberwar doesn’t change it significantly.

Today, all confrontations between the nuclear powers are constrained from total war by the threat of nuclear weapons and other devastating technologies. The tensions between the United States and any other Great Power are relegated to low-intensity conflicts with proxies, political struggles, and economic competition. Postmodern war depends on international tension and the resulting arms race that keeps weapons’ development at a maximum and actual military combat between major powers at a minimum. Real wars still happen, sometimes despite what the Great Powers wish. High-intensity, large-scale war could always break out, which in part explains the growing efforts to constrain violent conflicts. But continuing illusions about the nature of war itself bedevil any attempts to bring it under control. War cannot be managed: it is not a science; it cannot be controlled. But the seductive logic of control theories is incredible. The latest batch of cyberwar and information theories are particularly sexy—and dangerously limited.

Cyberwar, the Next Step?

Information war must be the hot new thing. It’s been on the cover of Time, Newt Gingrich has given a speech about it, Jackson Browne has a song called “Information Wars,” Tom Clancy has a novel, and RAND has a big research review.6 “Cyberwar is Coming!” exclaims the title of John Arquilla and David Rondfeldt’s influential article from 1993. Not the kind of staid academic warning one expects from analysts in RAND’s International Policy Department or from political science journals. The article had little in it that hadn’t been mulled over by non-RAND academics, science fiction authors, and middle-level military officers who have been worrying about the impact of the information revolution on war since the early 1980s, and it wasn’t even much different from certain currents of military thinking that can be traced through the whole history of war back to Sun Tzu’s The Art of War. But it has certainly caught on, spawning dozens of similar articles and coverage in the mainstream press.

There are three distinct elements of cyberwar that its proponents see as crucial.7 First, there is the illusion that war can be managed scientifically. This is a very old idea that goes back at least to the 1500s. Second, there is the realization that war is in large part a matter of information and its interpretation, especially as politics, and that it is in this realm that the metarules of war are set that determine who wins. This is not a new concept. It can be found in The Art of War, and it is the central insight of the whole range of guerrilla (“little”) wars that includes ragged, colonial, irregular, and counterinsurgency wars and low...